“You never work with a blank canvas,” says landscape architect Mikyoung Kim, M.L.A. ’92. “Every site, every neighborhood, has a depth of history that we have to listen to.” This is particularly true of a project she’s been working on for almost three years, a 14-acre park in Detroit, surrounding a century-old train station, which the Ford Motor Company recently bought and is transforming into an “innovation hub” for transportation technology. (“Kind of like Kendall Square,” Kim says, but for driverless cars and electric vehicles.)

From the beginning, the project intrigued Kim, whose Boston-based firm, Mikyoung Kim Design, specializes in “restorative landscapes,” both ecological and human. A former musician and studio arts major, Kim is known for urban gardens and plazas that combine nature and sculpture, weaving together cultural histories and civic identity. Her works are interactive, artistic, and often movingly inventive: a wooded garden near Walden Pond whose weathered-steel, serpentine fence seems almost organic; a botanical garden in Virginia with native trees chosen for the sound their seeds make in the late autumn wind; a restored canal in Seoul, Korea—the Cheonggye River, covered until recently by a highway—where a pedestrian corridor draws people down to the water, which is decorated with stepping stones quarried from both North and South Korea.

Swimmers in Seoul's Cheonggye River

Photograph courtesy of Mikyoung Kim Design

The Detroit train station, Michigan Central, was once the city’s main passenger depot, a grandiose Beaux-Arts behemoth located just south of downtown; in 1988 it was closed and then abandoned. There is history, too, in the disused school book depository nearby, designed, like so much of Detroit, by the architect Albert Kahn; its renovated laboratories and studios will be the first part of the project to open later this year. The site’s juxtaposition between an older industrial era and the current high-tech moment offers opportunities for landscape design, too, Kim says: “As technology advances, it actually becomes more invisible and allows us to make the landscape more responsive.” She offers an example: instead of streetlights that flick on at dusk and stay on all night, producing light pollution that’s been shown to affect public health, “We’re starting to experiment with systems where you walk through a landscape that lights up as you engage it, and dims down when you leave.” New technology, in other words, can return users to a past way of life, when people living in cities could still see the stars at night.

But the history Kim is thinking of at the Ford site goes deeper: for decades, the train tracks separated Corktown—one of Detroit’s oldest neighborhoods, now a diverse and gentrifying area of young families—from Mexicantown, a Hispanic community, vibrant and growing, though less well-off. “How do we change that?” Kim asks. One answer is by turning the station’s elevated tracks into a platform connecting the buildings, installing bike paths and pedestrian walkways—with “gateways” leading out into the neighborhoods—and planting more than 500 trees, knitting community to community under a canopy of leaves.

Rendering courtesy of Mikyoung Kim Design

Ecologically, the Ford site collects a huge volume of stormwater (finding artful solutions for excess water turns out to be a frequent creative challenge for Kim), which in her design will be cleansed and “daylighted” into pools or perhaps a ring of mist that people can walk through—something sculptural and interesting, she says, but not hidden: “Part of the job of a landscape is to teach, and I think it’s important for people in a city to understand that this is a system that’s constructed, to see what the parts are, and how it works.”

These bedrock beliefs—the impossibility of a blank canvas, the importance of bringing buried histories to light—have been with Kim since long before she was a landscape architect. “It’s very personal for me,” she says. The daughter of Korean immigrants, she grew up in Connecticut, one of only a few people of color in her monochromatic world. “I know what it feels like to be invisible, to be voiceless,” she says. “With these civic spaces”—the park in Detroit, and similar projects in Houston, Miami, Chapel Hill, Boston, and Cambridge—“I really do try very hard to hear all the points of view, to look at all the history....Landscape can be a way of hearing everyone’s voice.”

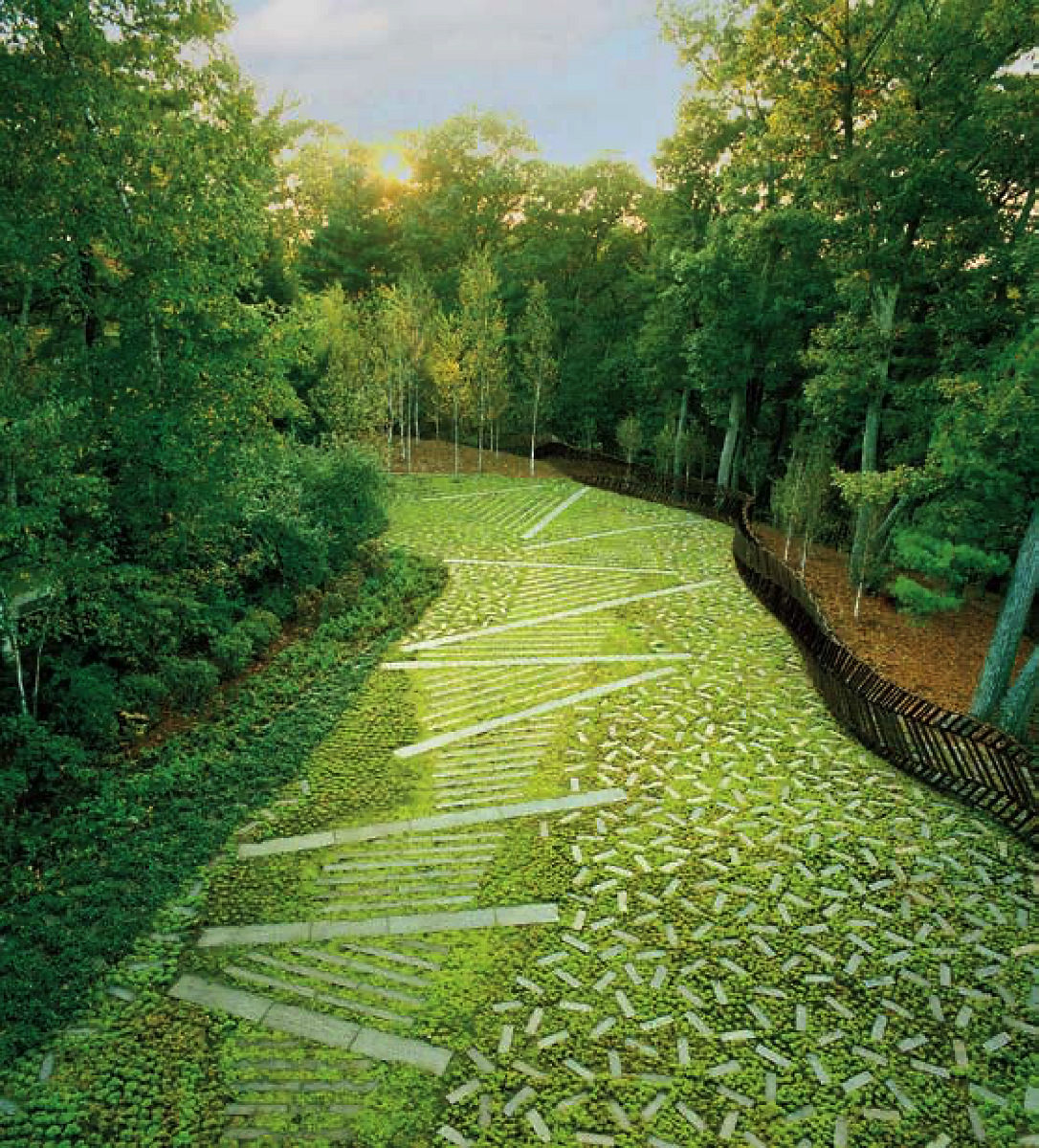

Farrar Pond Garden in Massachusetts

Photograph by Chris Brown

Until college, Kim was striving to become a concert pianist. She remembers her parents taking out a loan to buy her an upright piano when she was five “instead of a car for themselves. They really believed in creativity; it’s something they imparted very deeply.” From then on, “It wasn’t really a normal childhood. I didn’t do Girl Scouts or anything like that. I had a relationship with music.” Scrapbook photos show a little girl in ponytails, her tiny fingers on the keys. After high school, she attended the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.

During college, though, she developed tendonitis in her left arm that made playing impossible. Suddenly, the future shifted: Kim’s life would have to be about something else. “I fell apart at first,” she remembers. “You lose a way of communicating with the world when you lose your ability to play music.” She turned to sculpture. After college, still searching for a career, Kim helped one of her professors install a piece of public art along the Charles River: “I loved that; it felt like a space I could inhabit.” Afterward, a summer program in design at Harvard led her to graduate study at the Harvard School of Design. She founded her firm in 1994.

Kim (pictured) with a sculpture she designed

Photograph by Chris Brown

For Kim, the idea of “restorative landscapes” refers to both the ecological and the human: much of her work focuses on vulnerable populations. One of the best known is the Crown Sky Garden at Lurie Children’s Hospital, a glass-enclosed box of light and color perched on the eleventh-floor terrace of a medical center in downtown Chicago. It offers an escape from the hospital for young patients and their families, a place where leaves rustle, and they can touch things and move freely. There are groves of bamboo trees and wooden benches that electronically emit birdsong and rain sounds. A resin wall of blues, greens, yellows, and purples curls through the room like a wave; whenever a child steps toward it, a virtual image of waves and bubbling water appears, intensifying as one comes closer. (The wall’s interactivity, Kim says, is intended to restore a measure of control to young patients whose lives are often defined by a lack of it.) High in one corner of the garden, a clear-walled “treehouse” enables the sickest children to take in the scene from above, separate but still connected.

The Crown Sky Garden at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago is a colorful, interactive escape. The sickest patients can take part from a glass “treehouse” above.

Top to bottom: Photograph by George heinrich; Photograph by hedrich blessing

Since the garden opened in 2014, Kim has since designed “healing gardens” and end-of-life gardens at children’s hospitals and medical facilities in Boston, Miami, and Washington, D.C. The Chicago project, like the others, came together after years of planning that included extensive consultations with sick children and their caregivers and family members. “The community process is so moving to me,” Kim says. “People bring you their stories, and you understand that you have this responsibility to make something that is restorative to them.”