Climate change, long a divisive political issue, has united humanity in at least one respect: like it or not, everyone will have to adapt to higher temperatures, more powerful storms, and record-breaking rainfall. On January 31, globally acclaimed landscape architect Kotchakorn Voraakhom, M.L.A. ’06, spoke about her climate-resilient designs for urban parks, campuses, rooftops, and buildings in her native Thailand, where “living with water,” as professor of landscape architecture and associate dean of academic affairs Niall Kirkwood put it in his introduction, “is the vernacular.”

Residents of Bangkok, dubbed by Western explorers “the Venice of the East” as early as the 1540s, “originally had homes on stilts,” said Kirkwood, “and the floating food markets that fed the population persist today. Communities were used to living on water, and flooding and inundation meant defense from neighboring countries, and food—particularly an abundance of fresh fish, and productive rice fields. Sediment was part of seasonal change, flooding was transformational and vital.” The city lies in a river delta, and as Kirkwood emphasized, “The Chao Phraya river was, and is, the lifeblood of Bangkok.”

As a child this boat was Kotch's favorite toy. She looked forward to the wet season.

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

“Kotch,” as she is known to classmates and colleagues at the Graduate School of Design (where she is teaching this semester), has fond childhood memories of annual flooding during the monsoon: it was something she always looked forward to, and a small red boat she’d use to navigate the flooded main street outside her home was her favorite toy. In Thailand, she explained, the seasons are not spring or summer or winter, they are “wet or dry.”

But the country’s relationship with water changed in July 2011, when a powerful tropical storm flooded northern and central Thailand. The floodwaters reached Bangkok in October, and the ensuing disaster led to damages estimated at more than $46 billion.

Bangkok, home to more than 10 million people, is known traditionally as the “city of three waters,” Kotch explained, and is ranked as the eighth most at-risk city for climate change-induced extreme weather. There is “water from the north,” which brings floods via the river. Then there are rain events, which, she noted, have become more intense. And last, there is sea-level rise, exacerbated in Bangkok by local subsidence of the land (driven by extraction of groundwater from irrigation wells). Now there is actually a fourth type of water, she said: water waiting to be drained. Intense rain events of 15 to 30 minutes flood roadways and shut the whole city down, as commuters in cars and on scooters wait for water to recede through street drains. Resilient planning, she said, means dealing with all of these risks, so her landscape designs seek to address them in several ways.

“It’s impossible to keep Bangkok from getting wet,” Kotch continued, but prior engineering solutions have done more harm than good, in her estimation, as planners attempted to channel water in concrete-lined canals.

Award-winning design of Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park

Screenshots by Harvard Magazine

Her approach is different. Slow the rainwater’s path to its destination, plan for flooding—even make it a feature—and store irrigation water in tanks and retention ponds for later use. In her 2017 design of Chulalongkorn University Centenary Park, for example, she transformed 11 acres in the heart of Bangkok into a public park. The design, on a three-degree incline, slows water 20 times better than a paved surface, and onsite water management, including artificial wetlands, enables the park to collect, treat, and retain a million gallons of water, making it an ideal backstop for overloaded sewer systems during heavy precipitation. The idea behind her designs, she said, is not to eliminate flooding but to make it possible to live with it.

In 2019, she and her firm, Landprocess, designed an urban rooftop garden of 1.73 acres, Asia’s largest, for Thammasat University (Thammasat and Chulalongkorn universities are friendly rivals, she said, “like the Harvard and Yale of Thailand”). The garden reduces temperatures by up to two to three degrees Celsius, reducing energy demand for cooling. Onsite solar panels can produce up to 5,000 megawatts of power per hour, and four retention ponds enhance cooling ventilation in the adjacent buildings. Other projects include the transformation of a hospital helipad into a rooftop healing garden, and the reclamation of abandoned infrastructure dating to the 1980s as a pedestrian walkway across the river.

Rooftop garden fashioned atop a hospital's helipad.

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

Kirkwood, who visited the Phra Pok Klao Skypark in January, described it as a Thai version of The High Line in New York City, but “more poetic and spatially innovative. Pedestrians pause at its midpoint,” he said, “and enjoy views of the river that were once only available to kings and queens and princesses.”

In a coastal resilience project, Kotch’s firm is working with a scientist to perfect designs that will enable the restoration of a mangrove forest.

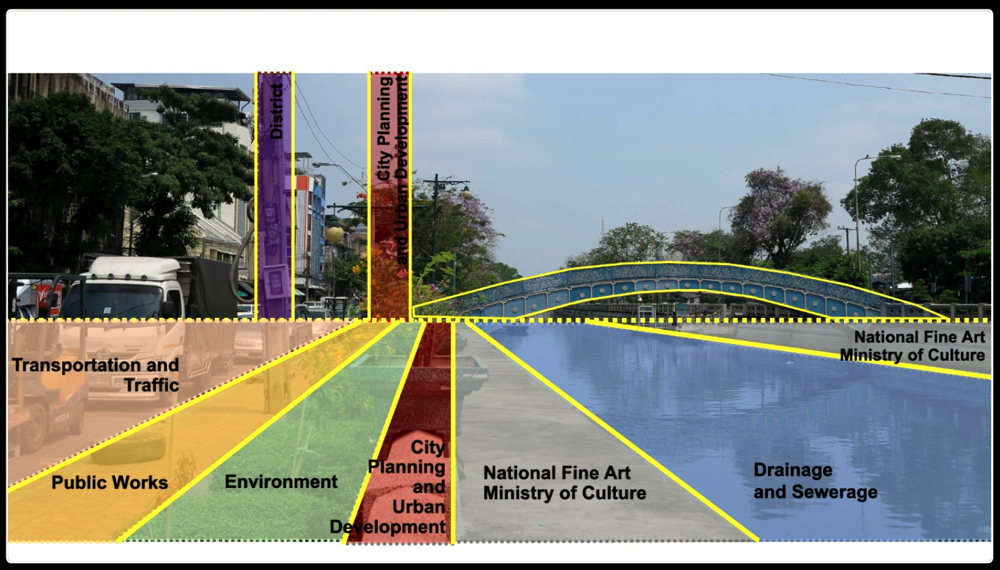

One of her key points was that adaptive design is not only about design—it is also about what she called “adaptive people.” In urban projects, she emphasized, much of her work involves identifying and coordinating among multiple stakeholders. In a narrow strip of land fronting one canal whose main purpose is drainage and sewerage, for instance, the immediate shoreline is under the jurisdiction of the National Fine Art Ministry of Culture. Beyond, parcels and decisions are variously subject to oversight by the department of city planning and urban development, followed by the department of the environment, then the department of public works, and finally, the department of transportation and traffic: a ribbon of bureaucracy that borders the waterway. To transform this urban tangle, she made clear, requires working with officials who may not be accustomed to working with each other—“breaking silos,” she said.

Canal bureaucracy

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

Kotch noted that resilience cannot be acheived in a single stage. Instead, “You dance with nature” she said. “The floods used to be the source of food, the source of fertilization….In the past 30 or 50 years, [we] completely turned our back to this natural change.” But now more and more people are advocating for what she described as Bangkok the way residents remember and love the city, not the way it is now.

She ended her presentation with an image of cracked concrete, with weeds growing in the crevices. “When I was a child at my playground, I tried to crack this piece of concrete for the plants to grow out,” she recalled. “I think landscape architecture is actually fulfilling my cracking ambitions. And I hope that I’m continuing to crack more space in the big concrete of Bangkok.”

Kotch ended her presentation with a visual of plants growing through cracked concrete, for her a symbol of her progress in designing resilient landscapes.