As a foreign correspondent, war reporter, and food writer, Wendell Steavenson has spent more than 20 years working in cities like Baghdad, Tehran, Jerusalem, and Tbilisi. She’s written about refugee cooks from Syria, the new spice barons of Madagascar’s booming vanilla market, and desperate “bank robbers” withdrawing their own money at gunpoint during Lebanon’s economic crisis. She’s covered the Middle East amid the aftermath of 9/11 and the War on Terror, and in 2015, she wrote about Egypt’s Arab Spring for The New Yorker. Her byline appears regularly in other publications including Granta, The Guardian, and the Financial Times. This past year, Steavenson, who was a 2014 Nieman Fellow at Harvard, has been in Kyiv, Dnipro, Lviv, Odesa, reporting for The Economist’s 1843 Magazine on the war in Ukraine and the lives of people caught up in it.

But her newest book, Margot, a coming-of-age novel set in the 1950s and ’60s, unfolds in a very different kind of environment, one that was the site of Steavenson’s earliest embedded experiences: the North Shore of Long Island, an area known for its palatial estates, lavish parties, country clubs, and WASP high society. The daughter of an American mother and a British father, she was born in New York and raised in London (“I’m properly half-American,” she lilts in her English accent), and since 2007 has lived in France. But as a child, she spent summers at her maternal grandmother’s house on Long Island. “So, I grew up going to those country clubs and being in that place, which is so particular and weird, a kind of strange ethnic enclave,” where she was both insider and outsider. She remembers her mother, a North Shore debutante during the late 1950s, telling stories about the protocols surrounding cotillions, parties, chaperones, and the strict dress codes for women: long gloves in the evening, hats at lunch. “It would have been unthinkable for two women to have gone out to have dinner together in a restaurant, or travel unaccompanied to another country.”

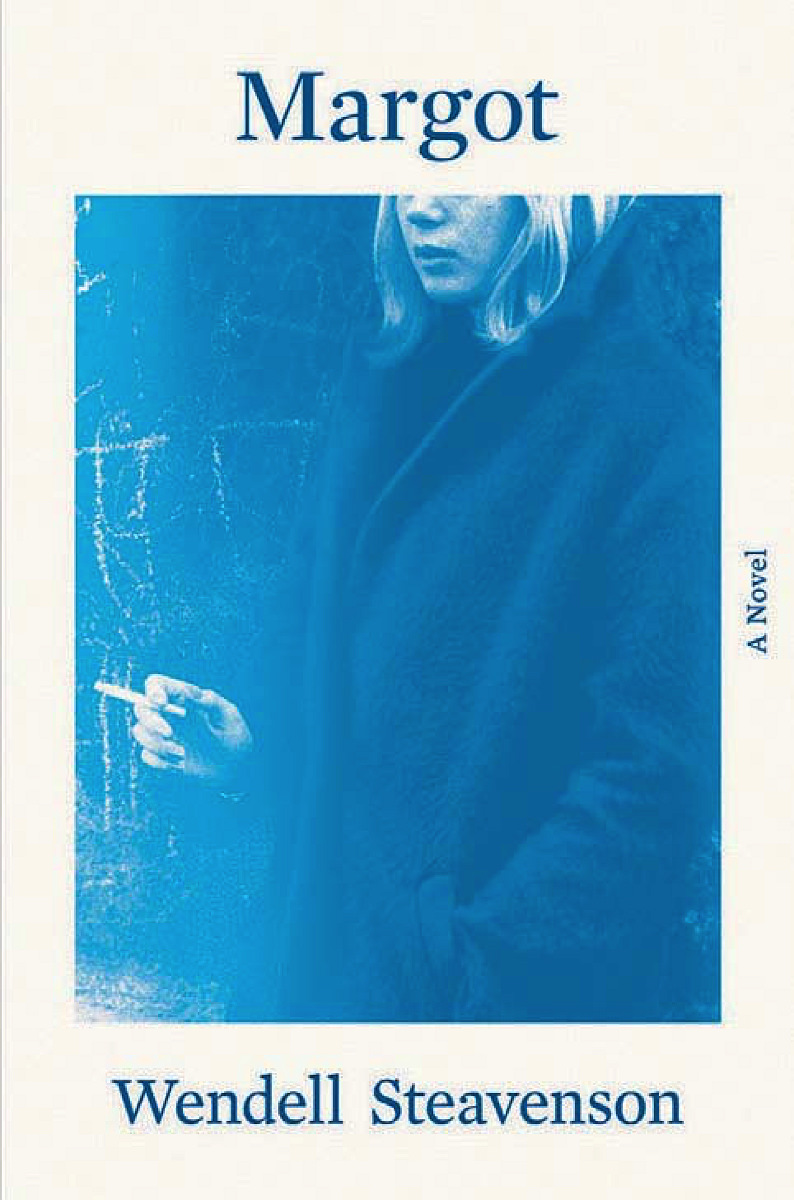

Thinking about her mother’s experiences, and her own a generation later, led Steavenson to the premise of the book, which was released in January. It follows Margot Thornsen, an oddball among her country club set (sensitive, academically gifted, awkwardly tall), as she grows into a young woman—and a 1968 Radcliffe College graduate—struggling to break free from a stultifying childhood and a mother single-mindedly fixated on her daughter’s marriage prospects. Meanwhile, all around her, the world is changing: the sexual revolution, the civil rights movement, Vietnam, assassinations and riots, campus protests. Steavenson also foreshadows the genetics revolution—and the moral conundrums that come with it—as Margot studies biochemistry under a professor whose ambition is to “slice and dice the human genome.” (The book sparkles with psychologically perceptive observations and poetically intense descriptive passages, and some of its most richly evocative scenes take place in the laboratory, with Margot peering through her microscope at the “tangle of chromosomes” beneath the lens.)

Steavenson chose Radcliffe as her protagonist’s academic destination partly because of the year she herself spent in Cambridge as a Nieman Fellow—“I had a sense of the place”—and partly because of Radcliffe’s history as a prestigious institution and a separate women’s college that no longer exists. The ambivalence over its merger with Harvard, the sense of something both gained and lost, the questions about equality and identity—these tensions carry through the novel as well.

“In hindsight, the 1960s looks like this great time of tearing everything down and new possibilities and breaking old paradigms,” Steavenson says. “And for some people it was. But I think it took much longer for most women of the ’60s generation to actually have careers and not be constrained by the assumptions that you would give up your job when you got married, or about what you could do and how much you’d be paid.” In the book, Margot rebels against those traditional assumptions, but also doesn’t quite know how to do it. “I think it was tricky,” Steavenson says. “I don’t think it was easy to imagine what might come next.”

Margot is Steavenson’s second novel. The first, Paris Metro, grew out of her experience reporting the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, where she was living at the time. She turned to fiction in 2018, after publishing three nonfiction books, including Circling the Square: Stories from the Egyptian Revolution and The Weight of a Mustard Seed, about the career and demise of a famous Iraqi general in Saddam Hussein’s regime.

She kept a journal that summer, “and I’ve been doing pretty much the same thing ever since.”

“I’m one of those people who always wanted to write,” says Steavenson, who studied history at Cambridge University. “That was nonnegotiable; there was no Plan B.” Journalism, like fiction, offered a way to tell stories, and traveling was a way to find them. “When I was 19,” she says, “the Berlin Wall came down, and for me that was formative as a writer.” In January 1990, she flew to Prague on her own to explore a city that six weeks earlier had been behind the Iron Curtain. “It was empty,” she recalls. “There were almost no restaurants open, almost no cafés. I walked and walked and walked; there were still Russian soldiers on the streets. It was magical and fascinating.” That summer, she and her then-boyfriend spent three months driving her Peugeot 205 around the Balkans and Romania and Bulgaria. “We were fascinated by the people, and they were fascinated by us,” she says. She kept a journal that summer, “and I’ve been doing pretty much the same thing ever since.” In the late 1990s, she spent two years living in post-Soviet Georgia, an experience that yielded her first book, Stories I Stole, a collection of anecdotes from a ruined, beautiful, absurd, sometimes terrifying country: periodic blackouts, fixed elections, a lover’s duel, a horse race in the mountains, plus plenty of wine, friends, and the occasional broken heart.

When she is not reporting from Ukraine and other conflict zones, Steavenson is working on a new novel (though it’s “too embryonic to know much yet”) and planning a sequel to Margot (the book ends on a cliffhanger, with the protagonist buying a one-way ticket to London). “I like toggling between nonfiction and fiction,” she says. “The cleanness of journalism helps discipline the fiction, and the empathy of storytelling helps you write articles that flow better, that pay attention to character and scene.” Perhaps there was a Plan B after all, but it was writing too.