If only because politicians frequently quote them, you’re likely familiar with poet Seamus Heaney’s stirring lines about the too-rare possibility that “justice can rise up, / And hope and history rhyme.” President Joe Biden, for one, has often cited the poem from which they come, including in the speech accepting his nomination at the Democratic National Convention in 2020, and Lin-Manuel Miranda recited it at Biden’s inauguration.

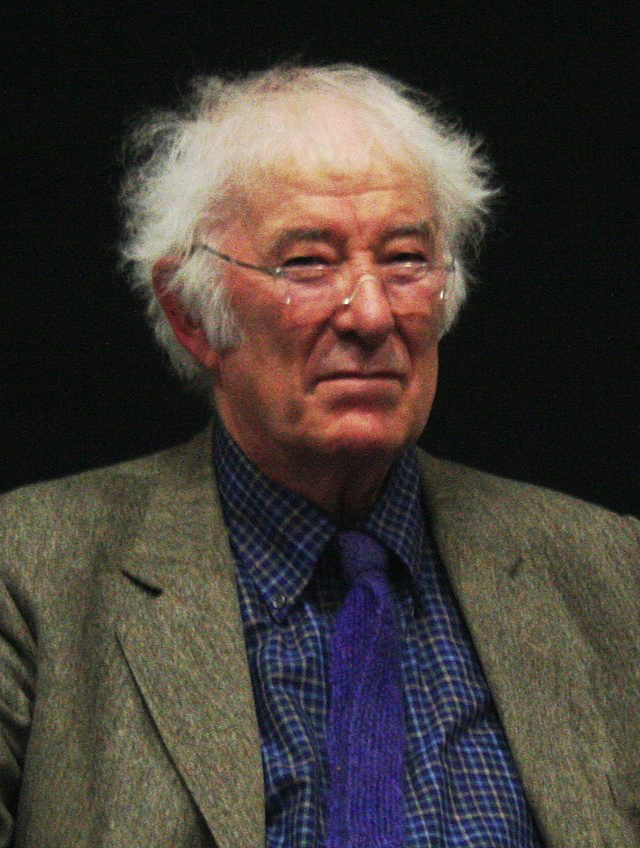

Seamus Heaney at the University College, Dublin in 2009

If you’re a Heaney fan, you might know that the lines come from a late Chorus speech in his 1990 play The Cure at Troy, itself a reworking of the Sophocles drama Philoctetes. You may also know that the late-twentieth-century Troubles—30 years of political and sectarian conflict between unionists, mostly Protestant, who want Northern Ireland to remain in the United Kingdom, and nationalists, largely Catholic, who would like to see it as part of a united Ireland instead—provided the play’s immediate context. The Irish government made the pursuit of peace in Northern Ireland a priority throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and today lines by Heaney from this climactic speech are displayed in every Irish embassy and consulate worldwide.

The Cure at Troy

Photograph courtesy of Marilynn Richtarik

But you probably don’t know that Heaney, Litt. D. ’98, wrote The Cure at Troy in Cambridge, during his tenure as Harvard’s Boylston professor of rhetoric and oratory. And you’re almost certainly unaware that John Hume, the primary architect of Northern Ireland’s peace process, also had important Harvard ties. Moreover, as I argue in Getting to Good Friday: Literature and the Peace Process in Northern Ireland, Heaney might well have been pondering Hume’s contemporaneous activities as he worked on the play. Now, at the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, signed April 10, 1998, that history is especially resonant.

A founding member of Northern Ireland’s Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), and a community organizer and civil rights campaigner before he became a politician, Hume put reconciliation at the top of his agenda throughout his career. As a constitutional nationalist, he favored Irish unity, but only on an agreed basis. By the mid-1970s, he was regarded as one of his party’s most inventive theorists. After a 1974 strike by unionist workers led to the collapse of Northern Ireland’s first power-sharing executive (in which he had served, too briefly, as minister of commerce), Hume concluded that no internal solution to its problems would be effective. Because the British government had allowed the strikers to prevail and the Irish government had been unable to persuade the British to protect the North’s new political institutions, he also inferred the need to get other powerful forces involved. Specifically, he sought to induce the United States to take an interest in Northern Ireland. The State Department had, at least since WWII, taken a pro-British line, so he set his sights on Congress and the White House.

Near the start of the Troubles, Hume decided that his political activity in the United States needed to focus on the center of power in Washington, D.C., rather than on Irish-America’s diffuse grass roots. And he believed that the road to Washington ran through Massachusetts. In the early 1970s, Hume established a close relationship with Senator Ted Kennedy ’54, LL.D. ’08. During a long one-on-one conversation in November 1972, he explained to Kennedy why the traditional Irish nationalist demand for British withdrawal from Northern Ireland did not address the fundamental issues there, which, in his view, could only be assuaged through respectful communication and negotiation. Converted to Hume’s approach, Kennedy was happy to help him enlist the support of other U.S. lawmakers. Hume’s lobbying had two main objectives: to challenge British dominance of U.S. foreign policy and subject the U.K.’s actions in Northern Ireland to critical examination; and to convince Irish-Americans not to support the armed struggle of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) but to push for a peaceful settlement instead.

All Hume needed to cultivate American influence was an extended period of residence in the United States; a fellowship at Harvard’s Center for International Relations during the 1976 fall semester provided that. Writer and filmmaker Maurice Fitzpatrick explains in his book John Hume in America: From Derry to DC that the invitation came from Williston professor of law Roger Fisher, who had a special interest in conflict resolution and would go on to found the interdisciplinary Harvard Negotiation Project, precursor to the acclaimed Program on Negotiation (see “Peacemakers,” March-April 2004). Hume no doubt found the intellectual atmosphere at Harvard stimulating, but an equally important attraction was the fact that Tip O’Neill, then House Majority leader and soon to be Speaker of the House, lived in Cambridge and returned there every weekend. After Kennedy introduced them, Hume and O’Neill soon became fast friends.

Hume and Heaney had known each other since their schooldays at St. Columb’s College in Derry and had kept in touch over the years, especially through holidays in Donegal. During Heaney’s first semester as a visiting professor at Harvard in the spring of 1979, Cambridge became another place for them to connect. He was soon offered an annual spring appointment at Harvard and, on Hume’s regular visits to Cambridge, would be included in gatherings while his old friend was in town.

In January 1988, Heaney wrote from Cambridge to his friend Brian Friel, a playwright with whom he served on the Field Day Theatre Company’s board of directors, confiding his desire to engage more closely with developments in Northern Ireland at what he saw as a crucial juncture. News recently had broken that their mutual friend John Hume, SDLP leader since 1979, had met with Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams. Because Sinn Féin refused to condemn IRA attacks in support of their shared republican objectives, the party had long been treated as an outcast by those who renounced violence in Northern Ireland. Hume’s willingness to talk with Adams thus represented a departure from his party’s established position and provoked a largely hostile response.

The chorus of condemnation would have been even louder had Hume’s critics known that he’d been conversing secretly with Adams for some time already on the invitation of Father Alec Reid. A Redemptorist priest based in Belfast, Reid believed the IRA might end its military campaign if the leadership were persuaded that a unified front of republicans and constitutional nationalists, including the SDLP and the Irish government, could achieve nationalist aims more successfully through politics than through force. As Hume’s friends, Heaney and Friel must surely have paid attention when his private relationship with Adams became a controversial public one.

The widely reported meeting between Hume and Adams in January 1988 had been occasioned by their decision to include their parties in their discussions; these party-to-party talks would begin in March. Before they did, though, Northern Irish people absorbed a series of shocks to rival any felt during the Troubles. On 6 March, three unarmed IRA members planning an attack in Gibraltar were shot dead at point-blank range by British undercover agents, confirming the opinion of many Irish nationalists that the government was pursuing a “shoot-to-kill” policy against republicans. Ten days later, at the funeral of the dead activists, mourners were attacked by a lone man with guns and grenades; three people were killed and more than 60 wounded, with republicans suspecting collusion between the gunman and the security forces. Three days later, as mourners gathered for the funeral of one of those murdered at the cemetery, two British Army corporals inexplicably drove their car into the procession and could not extricate themselves. Members of the crowd, fearing another attack, pulled them from their car, beat and stripped them, and shot them dead.

Tensions on all sides were running so high after this terrifying fortnight that Heaney attracted negative attention to himself at a banquet where he accepted the Sunday Times Award for Literary Excellence. Commenting on the double standard of regarding republican military funerals in Belfast as “a tribal and undesirable form of solidarity” while those in which “the victims were British soldiers” were “somehow immunized against tribal significance,” Heaney reminded his listeners that “local Belfast paranoia—generated by a recent graveyard bombing and shooting—played some part in the shamefully automatic cruelty and horror of the two British soldiers’ deaths which followed.” Some of those in attendance shouted “rubbish” after Heaney’s comments—an unusual if not unprecedented response to his words.

I was a senior during the spring of 1988, enrolled in Heaney’s course on twentieth-century British and Irish poetry. Looking back on that semester, I cannot recall being aware of any of this. I remember Heaney as an excellent professor, whose lectures were accessible and who always seemed completely focused on what he was telling us. This impression says more, I’m sure, about my obliviousness to current events at the time than it does about Heaney’s poise under pressure, though the latter was clearly immense.

In an atmosphere in which it took some fortitude for Heaney to align himself publicly with an Irish nationalist position by criticizing “mainland” British complacency, Father Reid was not wrong to suppose that republicans and constitutional nationalists should be able to identify broad areas of agreement. But the three 1988 encounters between Sinn Féin and SDLP representatives (the first took place just days after the last Gibraltar-related funeral) resembled strained arguments more than the exploratory discussions previously conducted by the parties’ leaders, and they gave the participants a clearer sense of their differences than of what they might have in common. Although they agreed in principle on Ireland’s right to “self-determination” and opposed any purely internal solution to Northern Ireland’s problems, Sinn Féin equated self-determination with a united Ireland and held to this as a firm objective. The SDLP, following Hume’s reasoning, pointed out that unionists, too, were part of Ireland’s population and thus shared in the right to self-determination. Because the British government in the 1985 Anglo–Irish Agreement had effectively stated that Irish unity and independence could come about through people who wanted it persuading those who didn’t, it seemed evident to SDLP members that the armed struggle was counterproductive. Because republicans did not share this view of the British government’s neutrality, the parties largely talked past each other. Nonetheless, the Hume–Adams dialogue, which now involved the Irish government as well as Father Reid, continued privately after the SDLP–Sinn Féin talks ended.

Heaney had been thinking about adapting the Sophocles play since at least November 1985—partly inspired by Michael Blumenthal, Harvard’s Briggs-Copeland lecturer in poetry and later director of creative writing, who showed Heaney the text of a lecture he’d delivered on the operation of justice in Philoctetes. In January 1990, Heaney finally agreed to produce a script of the play that Friel jokingly referred to as Phil O’Ctetes for that fall’s Field Day tour and, back at Harvard, he got to work. Because he did not know Greek, he was delighted to discover, in the bowels of Widener Library, a late-nineteenth-century literal translation of the play. He compared this with two more literary translations in compiling his own “version,” written mostly in blank verse apart from the Chorus speeches and a few passages of prose. Field Day produced The Cure at Troy that fall, touring throughout Ireland during October, November, and early December.

The public aspect of theater’s production and reception took Heaney aback as a writer accustomed to the privacy of poetry. He told an interviewer during the Field Day tour that “I wrote the words in a study at Harvard, just concentrating on being faithful to the text, thinking abstractly: ‘This must be speakable.’ That was all.” He knew, though, that people attending a Field Day play expected political commentary, however oblique. So what associations did he expect the play to evoke for contemporary Irish (and especially contemporary Northern Irish) audiences?

Philoctetes was a legendary Greek warrior who won fame as an archer, having inherited the magical bow and arrows of Hercules. Bitten by a snake during a stop the Greek forces made on the island of Lemnos on their way to Troy, he was left behind by his comrades when the wound became infected. Ten years into the war, the Greeks learned from a Trojan soothsayer that Troy could not be taken without the assistance of Philoctetes and Neoptolemus (son of the pre-eminent Greek warrior, Achilles). The two men were brought to Troy, Philoctetes was cured of his wound, and the Greeks proceeded to prevail.

In the Sophocles play, Odysseus—responsible, in many versions of the story, for the abandonment of Philoctetes—arrives on Lemnos with Neoptolemus in tow, determined to obtain the magic bow by any means necessary. He proposes that Neoptolemus, who was not a member of the original expedition to Troy, should approach Philoctetes, gain his trust by telling his own story of mistreatment at the hands of Odysseus, and take the bow when he lets down his guard. Neoptolemus meets Philoctetes and lies to him along the lines suggested by Odysseus. Instead of seizing the bow, however, he befriends (or pretends to befriend) the outcast, agreeing to take him home to trick the wounded warrior into coming with him willingly. Philoctetes trustingly allows Neoptolemus to hold the bow, after which the older man is overcome by a paroxysm of pain that pushes him to the limits of his endurance. While Philoctetes sleeps after this fit, the Chorus urges Neoptolemus to slip away with the bow, but he insists that it will be useless without its owner—that Philoctetes himself must be given his destined share in the Greek victory to fulfill the oracle.

When Philoctetes wakes, they start walking to the ship, but Neoptolemus, overcome with remorse about deceiving the injured man, feels compelled to tell him the truth about where they are going and why. Philoctetes then angrily refuses to leave, demanding that Neoptolemus return the bow. He is about to do so when Odysseus enters and commandeers it. After a heated argument between Philoctetes and Odysseus, the latter orders Neoptolemus back to the ship with him. The Chorus urges Philoctetes to reconsider and come to Troy of his own free will to be healed and win glory, but he remains adamant in his refusal. Neoptolemus and Odysseus come back, and, in direct defiance of his commanding officer, Neoptolemus returns the bow to Philoctetes. When Odysseus leaves to summon the rest of the Greeks to punish the insubordinate youth, Neoptolemus pleads with Philoctetes one last time to put aside his grievance and come with them. The older man refuses still and reminds him of his earlier promise to take Philoctetes home, and Neoptolemus agrees to keep it despite his fear of his comrades’ retribution. As they prepare to depart, Hercules appears and orders Philoctetes to go to Troy to fulfill his destiny. The intrusion of this deus ex machina at the end of Philoctetes comes as a resounding anticlimax.

But the point of the play, for Heaney as for Sophocles, lay in the difficult decisions Neoptolemus must make without foreknowledge of their outcome. Neoptolemus’s moral quandary was what drew Heaney to Philoctetes, for reasons that had everything to do with his Northern Irish upbringing. “That kind of dilemma,” he observed in an interview with poet Dennis O’Driscoll, “was familiar to people on both sides of the political fence in Northern Ireland,” where “to speak freely and truly on certain occasions would be regarded as letting down the side.” Heaney felt, because of having grown up there, “a fascination with the conflict between the integrity of the personal bond and the exactions of the group’s demands for loyalty.”

Neoptolemus is the only one of the play’s three main characters able to acknowledge the legitimacy of both sides of this conflict. The dramatic interest resides in watching him move between the fixed poles represented by Odysseus and Philoctetes, who cling tenaciously to their belief in the righteousness of their respective positions. Neoptolemus is also the only character to change significantly during the drama. At first, although he deplores the deceitful methods advocated by Odysseus, he does not doubt their right to deprive Philoctetes of his bow to win the war. He even suggests that they should simply overpower the crippled man and take it by force. By the end of the play, he has become, effectively, a traitor to the Greek cause through his unwillingness to lie to Philoctetes. This does not mean, however, that Neoptolemus thinks Philoctetes is right to refuse to help the Greeks. Rather, he feels personally obligated to keep his promise to the older man and not to take advantage of his trust or force him to come to Troy against his wishes.

On one level, The Cure at Troy can be read as Heaney’s defense of a political stance that involves seeking to understand various positions on an issue, whatever one’s own opinion about it may be. As Neoptolemus’s case demonstrates, this attitude is not without risk. A genuine willingness to listen to different points of view and seek common ground can leave one “[d]angerously out between” opposing factions, as Heaney wrote about his friend Sean Armstrong, a social worker killed in 1973 because of his activity on both sides of the sectarian divide. John Hume also left himself open to charges of double-dealing or worse as he continued to converse secretly with Gerry Adams throughout the period when Heaney was working on his play, while at the same time participating in an initiative by Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Peter Brooke to convene talks involving the British and Irish governments and the four main constitutional parties in the North: the SDLP, the Ulster Unionist Party, the Democratic Unionist Party, and the centrist Alliance Party. Hume’s then assistant Mark Durkan, one of the few people who knew about both sets of conversations, recalls that Hume regarded them both “as necessary, compatible and potentially complementary” and that he sought to build “layers of understanding in both dialogue channels so that a convergence could be achieved.”

In this context, Hume’s developing personal relationship with Adams acquires a significance akin to that between Neoptolemus and Philoctetes in the play, and it is worth remembering that Hume’s emotional insight and integrity were the qualities Heaney chose to emphasize in a November 1969 essay about his friend, asking, “What other politician has Hume’s attentive intelligence and sympathy for his opponent?” Adams, who understood that “We were more the ‘enemy’ than the British and the unionists for some of the SDLP leadership,” appreciated that Hume risked his reputation by continuing to meet and talk with him. Like Neoptolemus, Hume sometimes acted in ways that seemed contrary to his own party’s interests in pursuit of what he regarded as higher aims, and political scientist Cathy Gormley-Heenan writes that “hindsight has shown that Hume’s sustained and successful attempts at engaging Adams in the [peace] process were undertaken at the expense of the SDLP’s electoral successes in later years.” Hume himself likely understood and accepted that this would be the case; this was, after all, a man said to have told colleagues who disagreed with his tactics that “If it’s a choice between the party and peace, do you think I give a fuck for the party?”

Heaney described The Cure at Troy as “a kind of ‘post-cease-fire’ writing avant la lettre,” although he understood that the uplifting sentiments expressed by his Chorus remained “in the realm of pious aspiration.” The vision he presents at the end of The Cure at Troy seemed utopian in 1990, but it would be realized before the end of the decade to an extent that no one could have predicted when the Field Day production was touring.