Costume shirts, flashy posters, and hand-edited scripts live on in Widener Library’s Judaica Collection as relics of a bygone—but not yet dormant—art form. Beginning in the mid-1800s, European children and their bubbes headed to the theater to watch performances in Yiddish. At the time, Eastern Europe had a millennia-old community of Yiddish-speaking Jews, and they wanted to act in their native tongue.

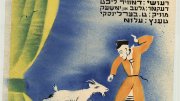

Poster for three New York City plays in 1904: Got, mensh un tayvel (God, man and devil), Shlomo Hokhem (Shlomo the wise), and Yeshivah bokhur Hamlet (Yeshivah student Hamlet)

Image courtesy of the Harvard Yiddish Theater Collection/Harvard Judaica Division/Widener Library

Troupes moved from shtetls to skyscrapers at the turn of the twentieth century as Jews immigrated to Western Europe, North America, and South America. New York City had dozens of Yiddish theater companies during the first half of the 1900s. The actors weren’t just sharing tales from the old country. Judaica Collection specialist Vardit Samuels says, “There were comedy and vaudeville and light entertainment, there was serious drama, there was a lot of experimentation in new vogue theatrical movements.” New York Yiddish theater troupes were at the forefront of the American modernist movement, performing plays with realistic styles and emotions while Broadway was dominated by melodramas. Later, some of those thespians made the jump from the Yiddish stage to the English-speaking screen, acting alongside stars like Gene Wilder and Harrison Ford.

Poster for Di Fraylekhe Kabtsonim starring the Burnstein Family in Haifa, Israel, 1963

Image courtesy of the Harvard Yiddish Collection/Harvard Judaica Division/Widener Library

Most practitioners and patrons of Yiddish theater were killed in the Holocaust. Postwar, assimilation chipped away at the Yiddish language, but the theatrical tradition persisted on a smaller scale. Holocaust survivors and their kin enjoyed robust Yiddish theater scenes in the United States and Israel through the 1970s, and some troupes still operate today (with great popularity, too, like the recent Off-Broadway Yiddish Fiddler on the Roof). Harvard’s collection is not stagnant, as it archives posters from modern shows and even collaborated with a student to put on a Yiddish opera. Though it now takes great chutzpah to perform in a nearly dead language, Harvard’s collection reminds us that Yiddish theater never lacked boldness.

Poster for Di Komediantke starring Sarale Feldman in Givatayim, Israel, 1985

Image courtesy of the Harvard Yiddish Theater Collection/Harvard Judaica Division/Widener Library