Among Harvard’s greatest treasures are people who revel in discovery and disperse dusty clouds of ignorance. Among them was Ursula B. Marvin, who teased solar system secrets from meteorites, contributed to deciphering the Moon’s evolution from Apollo samples, and helped create the field of planetary geology—becoming a pioneer among women reshaping American science.

Early Life and Academic Beginnings

Ursula Bailey was born in 1921 in Bradford, Vermont; her father was an entomologist and her mother a teacher. Their home had spacious views of the White Mountains to the east that Bailey found breathtaking in evening alpenglow—a landscape that gave her a great love of the outdoors.

Bailey went to Tufts to major in history but became fascinated with geology. She said, “Geology lit a fire. I fell in love with it the first week.” Sadly, her professor, Robert Nichols, Ph.D. ’40, refused her request to switch majors, saying, “You should be learning to cook!” Her interest stymied, she took additional geology, physics, and math courses while completing her history degree in 1943.

Another Tufts geology teacher, Katharine Fowler-Billings (whose husband Marland Billings, A.B. ’23, Ph.D. ’27, chaired Harvard’s geology department), encouraged Bailey to apply to Radcliffe for graduate studies in geology. Bailey was awarded a scholarship and became the first woman to hold research and teaching-assistant positions in Harvard’s geology department. She completed a master’s degree in geology in 1946 and, after a short stay at the University of Chicago, reenrolled at Harvard to work on a Ph.D., studying the mineralogy of meteorites.

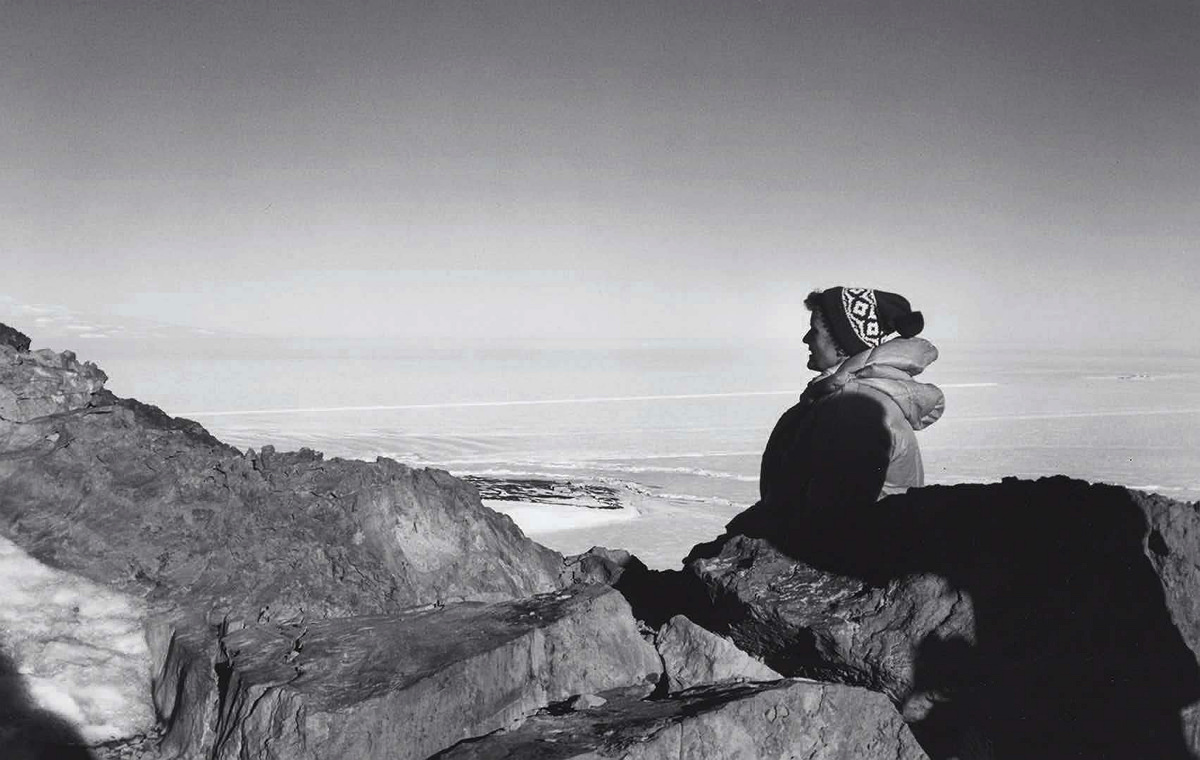

Ursula B. Marvin on a rock outcrop in Antarctica (1978-1979 season)

courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution image SIA2015-002618

She soon met another student, Tom Marvin ’39, Ph.D. ’52, to whom she would be married for more than 60 years. Ursula completed her doctoral coursework, but the couple was enticed to Brazil and Angola for mineral exploration in 1952 before she completed other degree requirements. After they returned to Cambridge, Ursula was offered a teaching position at Tufts by Nichols, who regretted his prior declaration, and then, in 1961, a post at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (later part of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) to study meteoritic samples of asteroids. Marvin spent the rest of her career there.

She quickly generated an enviable bibliography, with five papers in Science and Nature. Harvard’s then-Department of Geological Sciences, recognizing excellence in its midst, offered her an opportunity to take the oral examinations she missed in 1952 and to bind her publications in lieu of a thesis. Marvin accepted and was awarded a Ph.D. in 1969. That year, when NASA turned to meteoriticists for their expertise with extraterrestrial samples, Marvin was among the first to analyze Apollo 11 samples from the Moon. She coauthored the lunar magma ocean hypothesis that still guides our ideas of early lunar evolution and the differentiation of planets.

Groundbreaking Contributions to Planetary Geology

Marvin’s passion for meteorites carried her to Antarctica, where she became the first woman to participate in the U. S. meteorite recovery program, spending two field seasons along the Transantarctic Mountains and another field season on Seymour Island to study a mass extinction. She wrote an authoritative description of the first lunar meteorite recognized from Earth’s south polar region, concluding that “while waiting for future space missions we have found an elegant means of significantly extending the range of planetary samples by making our yearly expeditions to Antarctica.”

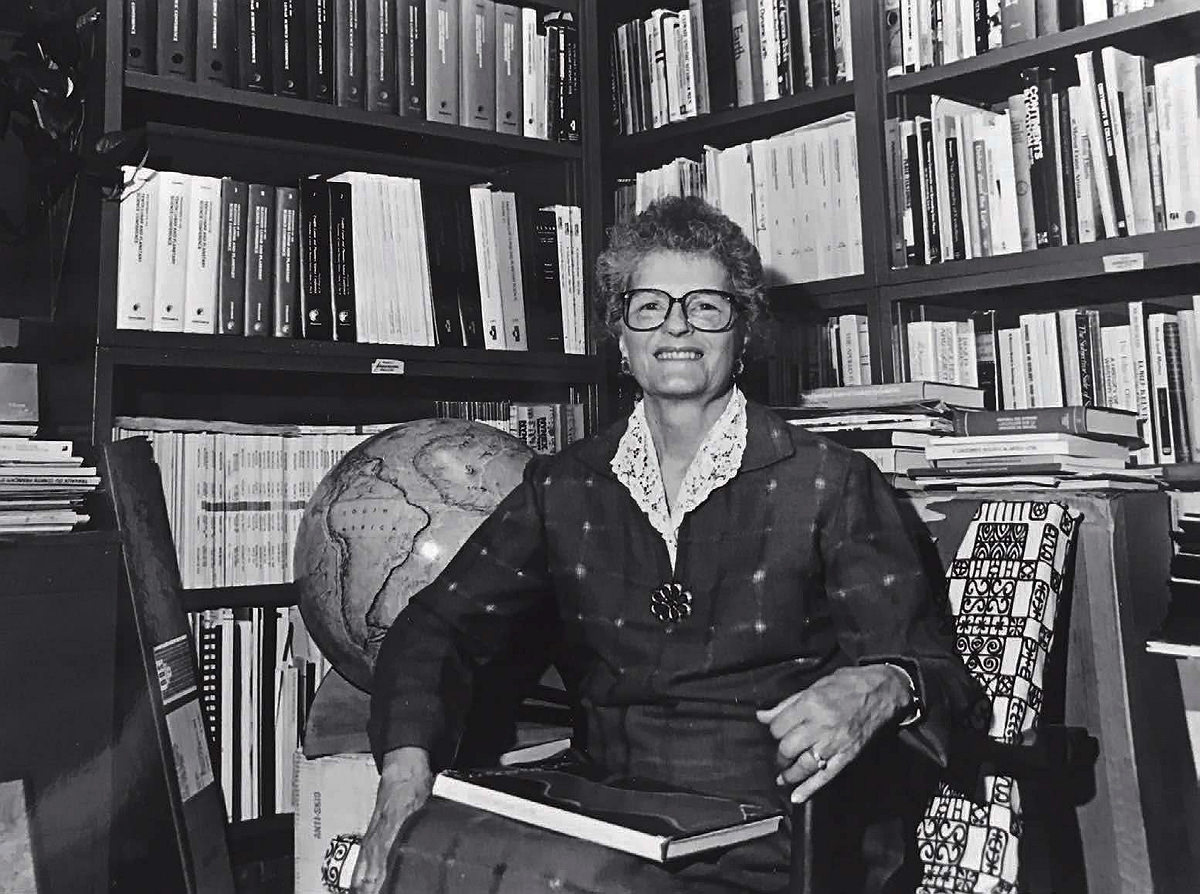

In her Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics office with her book, Continental Drift: The Evolution of a Concept, on her lap

Image courtesy of the Center for Astrophysics|Harvard & Smithsonian

While carving a niche for herself in history, Marvin drew upon her original education to become one of the most important chroniclers of geologic history. Early in her career, she wrote the influential book Continental Drift: Evolution of a Concept. She continued to probe science history, writing wonderful analyses of how the concept of meteorite falls evolved, and evaluating the historical implications of the impact mass extinction hypothesis (linked to the dinosaurs’ demise)—concluding it was a greater shift in geological tenets than plate tectonics. Marvin also captured a series of oral histories from other pioneers in twentieth-century meteoritics and the nascent field of cosmochemistry—a well-documented resource for future historians.

Legacy and Honors

Alongside her world-class research, Marvin overcame cultural and professional impediments and is appropriately celebrated for being an important pioneer for women in geology, meteoritics, and planetary science. Prominent among her honors are an eponymous asteroid and Antarctic nunatak.

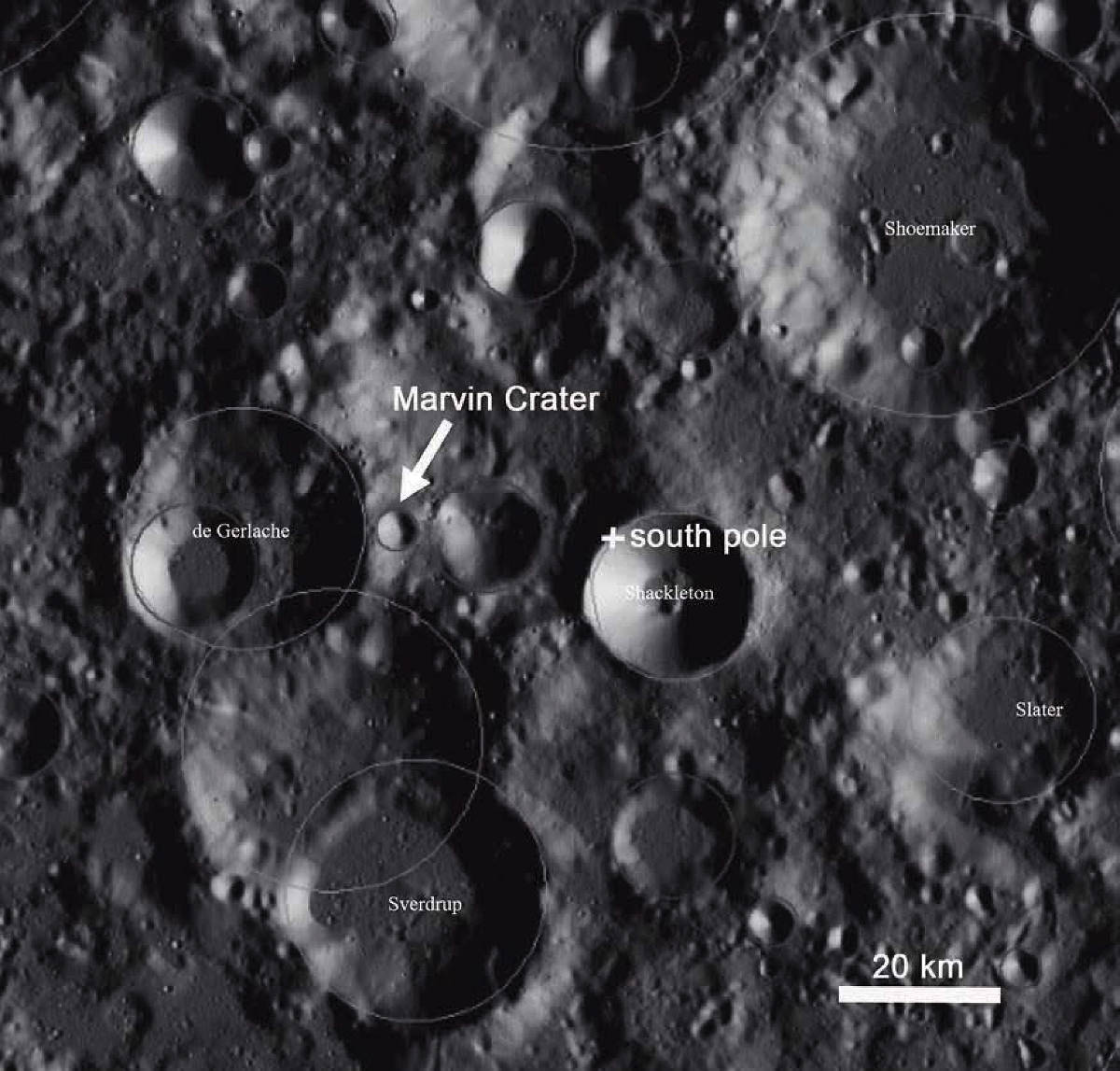

The 4.6-kilometer (diameter) Marvin impact crater near the lunar south pole—a region soon to be explored by Artemis astronauts

Images from top left: Graphic generated by the author using Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter data

Marvin died in 2018, but her work continues to resonate as NASA sets its sight on the Moon again. The Artemis program (named after the twin sister of Apollo) will land astronauts near the lunar south pole. Geologists mapping the region named a polar crater Marvin in celebration of her extraordinary work. Artemis is designed, in part, to inspire children in an increasingly diverse way; among the astronauts inspiring them will be women and people of color. Astronauts walking through terrain bearing Marvin’s name make a scientific legacy as bright as a full Moon.