“Free should the scholar be,” claimed Ralph Waldo Emerson in 1837. “Free even to the definition of freedom.” Speaking to Harvard’s Phi Beta Kappa Society, the writer was inviting students to engage in debate and inquiry unrestrained by any kind of censorship, surveillance, or preconceived notions. Radical intellectual freedom is still considered the foundation of the American university. Each year at Commencement, Harvard’s president confers doctoral degrees by saying that he entrusts graduates with “the free inquiry of future generations.” This May, after almost eight years of study, I was among those standing in red robes that granted official entry to the halls of scholarship, with the paradoxical duty of free thought.

But this year, the celebration of freedom was joined by a reminder of its opposite. As the Class of 2023 received their degrees in the open air of Tercentenary Theatre, the nearby Houghton Library exhibition “Sentences: Prison Writing through the Ages” demonstrated how intense intellectual commitment can arise behind bars. If academic writing is supposed to develop in freedom, how do we understand the words of incarcerated authors?

In contemporary America, this question is critical. The United States has the largest prison system in the world, with more than 2.1 million people incarcerated. The exhibition features materials from nearly 50 writers who created works during or after their confinement, from memoirs, poetry, and novels to philosophy, history, and letters. “Sentences” is one of several 2023 exhibitions that have reflected on mass incarceration in the United States: “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration” is currently on view at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and on Alcatraz Island, “The Big Lockup” examines the site’s history as a military and federal prison.

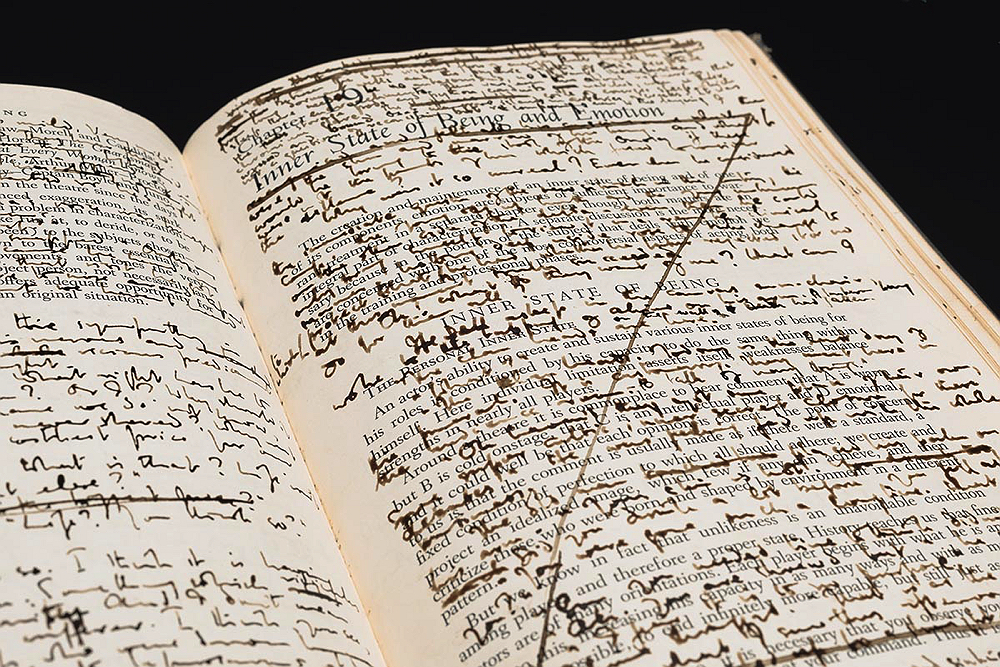

Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, a poet, playwright, and political activist, spent 22 months in prison during his home country's civil war, where he wrote on cigarette wrappers and in between the lines of other books.

Image courtesy of Houghton Library

At Houghton, curator Peter X. Accardo decided to take a more global perspective. “You might easily conceive of an exhibition of prison writings from America in the 1960s and ’70s,” he says. “You could fill up a room with that.” But instead, he chose a broader sweep: “Across the world, across the centuries, and across all cultures, prisons are sadly a part of our world.” The exhibit includes writings by Mahatma Gandhi, Oscar Wilde, Wole Soyinka, and Rosa Luxemburg. The first thing visitors see upon entering is a manuscript of Dostoyevsky’s The House of the Dead, which expands on the novelist’s experiences in the Siberian labor camps.

“Sentences” displaces the usual condemnatory image of prisoners, elevating them to thinkers, writers, and philosophers. This has the perplexing effect of making the jail not just a place of imprisonment but also an intellectual institution. The exhibit’s inspiration, Accardo says, stemmed from a personal, though very different, experience of confinement. “I was hospitalized, and I brought with me a copy of Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, a book I had read about but never actually read.” The Roman philosopher and senator had written it during a yearlong imprisonment in the early sixth century as he waited to be tried—and, later, put to death—for treason. “I found a beautiful 14th-century manuscript,” Accardo says, “with the illuminated initial that depicts a dialogue between Boethius and Lady Philosophy, discussing the transience of most mortal things and that we can transcend almost any obstacle we can encounter in life through the kind of higher plane of thought and philosophy.” It struck him that Boethius’s poverty of experience had produced a wealth of critical imagination.

The exhibit’s global scope was a challenge not only for the curator but also for the library. Accardo found gaps in the collection as he searched for representative voices from around the world. No Easy Walk to Freedom, a collection of Nelson Mandela’s speeches, articles and letters—including his famous Rivonia trial speech, delivered from the dock in 1964—was acquired during the preparation for the exhibition. “I think in a continent like Africa,” Accardo explains, “prison writing, diaries, memoirs, are a really important genre to talk about the different political upheavals that have taken place in recent years.”

The exhibit also casts a critical eye on how American culture has represented prison. Jail has long been glamorized by the media, and sites like Alcatraz have been transformed into tourist attractions. “Sentences” confronts this development, juxtaposing works like the “detention diary” of Nigerian environmental activist and writer Ken Saro-Wiwa with a copy of Piper Kerman’s Orange is the New Black, the memoir on which the eponymous TV drama is based, and Stephen King’s The Green Mile, a serial novel that later became an Oscar-winning movie starring Tom Hanks.

Although prison writings span eras, most of the pieces in this exhibit belong to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Seen through the lens of time, “Sentences” carries a certain sense of urgency and acceleration. It revisits controversial moments in recent American history, including materials related to the Black Panther Party. The decision to address the organization’s history connects with other contemporary artistic efforts to redefine the group, such as filmmaker Bouchra Khalili’s 2018 short documentary Twenty-Two Hours, and a current exhibit on Black Panther propaganda at the Poster House in New York City. Overshadowed for many years by a reputation for violence, the Black Panther Party was an important source of inspiration and training for a generation of activists and politicians, and it organized community service programs that offered food, clothing, and transportation to neighborhood residents.

The Houghton exhibit includes letters written by Angela Davis, who in 1970, was accused of supplying firearms to the group responsible for attack on the Marin County Civic Center, a kidnapping and attempt to free Party activist George Jackson, who was in custody and charged with murder. Four people died in the incident. Davis’ correspondence, displayed in the exhibition, helped launch a global campaign to fight for her freedom—a conspicuous example of a larger cultural strategy linked to letters. Accardo laments that, due to its size, he could not include a Black Panthers newspaper that reprinted letters from prison. “These were a means by which people from that community who were incarcerated were able to get their word and their messages out to the public that needed to hear from them,” he says.

Instead of certainties, the exhibition emphasizes the political paradoxes of mass incarceration. Lady Constance Lytton’s “Prison & Prisoners” presents what is probably one of the most cruel illustrations in the exhibit. A British suffragette, writer, and prison-reform activist, the aristocratic Lytton disguised herself as a seamstress and endured the brutal, and unequal, treatment that working-class women received in jail, exposing practices such as tube force feeding and hard labor. Mahatma Ghandi’s “Jail Experiences Told by Himself” presents a different dilemma: Why should someone face prison time for defending peace?

For scholars of Latin America, the Houghton exhibit holds particular resonance. All of the materials remind visitors of the central role prison plays when assessing a government’s democratic credentials. Today, this is an urgent lesson. I cannot help but think of President Nayib Bukele’s construction of a massive prison in El Salvador—intended eventually to hold 40,000 inmates—and of potential presidential candidate Evelyn Matthei arguing for reinstating the death penalty in Chile, my home country. The exhibit exposes society’s fraught relation to punishment by bringing these contradictions to the surface.

The implicit statement in “Sentences” is that writing not only can denounce the dire conditions of imprisonment, but can also help imagine a way out. In Felon, Reginald Dwayne Betts creates poems by using a black marker to obscure long passages of text in official court documents, leaving only selected words uncovered, mimicking the process of redaction. In 1996, at age 16, Betts was charged with six felonies related to an armed carjacking, tried as an adult, and sentenced to prison. Reading poetry, he has often said, saved his life while he was incarcerated. Today he is a poet, a scholar and graduate of Yale Law School, and the founder of Freedom Reads, an organization that builds libraries inside of prisons. Houghton’s exhibition actively engages with Betts’s artistic and moral sensibility. “The voices of people who are currently incarcerated, who formerly didn’t have the ability to be heard, now have advocates that are allowing their writings to be broadcast,” Accardo says. “Now these are people that have the most valuable testimony to offer in this current debate about the state of prisons in this country.”

The exhibition’s impact lingers, inviting a return to Emerson’s words. It is possible to free ourselves, even from the definition of freedom, and to hear the muted sounds of people behind bars writing their liberty.