Drew Gilpin Faust, then dean of the Radcliffe Institute, turned her historian’s lens on herself in “Living History” (May-June 2003), an account of her Virginia girlhood in the 1950s, amid intense resistance to implementing the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education striking down segregated, “separate but equal” public schooling. In her new memoir, Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), Faust, now president emerita, extends the story through her college education and arrival—via the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War—at the brink of adulthood in the traumatic year of 1968.

This excerpt details a period of formative activism. Faust spent the summer of 1964 in civil rights work in the South, and then enrolled at Bryn Mawr. After working on a rather feckless Students for a Democratic Society organizing project (she paid 25 cents for a mimeographed copy of the founding “Port Huron Statement”), she found herself in the spring of her first year again caught up in national affairs. Her exposure to Selma, where John Lewis suffered a fractured skull during Bloody Sunday, the first voting rights march, proved to be of lifelong importance: he received an honorary LL.D. in 2012; she attended the fiftieth anniversary of the Selma marches in 2015; he joined in affixing a plaque to Wadsworth House acknowledging Harvard’s slave legacy in 2016; and he was the guest speaker in 2018—Faust’s last Commencement. The book title is his phrase: a call to activism and advocacy for change. From chapter 10, “The Class of 1968.”

—The Editors

By the beginning of a new year and a new semester, I was no longer trying to organize South Philadelphia, but I soon found myself drawn into a more dramatic expression of my concerns about racial justice and civil rights. As I look back, I think of a story that Bryan Stevenson, lawyer for the condemned and dispossessed and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, tells about his life, a story that has helped me understand how I ended up in Selma, Alabama, in March 1965 when I was supposed to be back in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, taking midterm exams and completing my first year of college. Bryan is a spellbinding speaker—maybe the best I have ever heard—who transports you into his world of experience and compassion. There is one personal memory he shares often. It is about his grandmother, who always held him so tight it hurt and offered words that he has never forgotten: “‘You can’t understand most of the important things from a distance, Bryan. You have to get close.’” Proximity, Stevenson came to recognize—to the condemned, to the oppressed, to the suffering—gave him a purpose and a foundation for action that the abstractions of newspaper articles or law school textbooks could never provide.

My summer experience in the South had given me proximity. I had gotten close, and I could not see stories of racial injustice and white violence in the same way again. The incidents being reported from the voting rights drive that Martin Luther King Jr. had joined in Alabama were not remote. Even if the particular individuals I had come to know—Eddie and Willie from Orangeburg, George from Birmingham, or the families of the four young girls who had been murdered in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church—were not the specific individuals now being beaten or killed, it was people like them, people who were confronting the same injustices and sharing the same dreams. I had become invested in them and in their struggle in a way I could not have been before they gave it tangible reality in my mind—and heart. I had to get close again. The moment of truth for me was Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, when I watched on television as unarmed protesters, including John Lewis and the formidable 63-year-old civil rights crusader Amelia Boynton, were clubbed to unconsciousness by state troopers determined to prevent them from crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

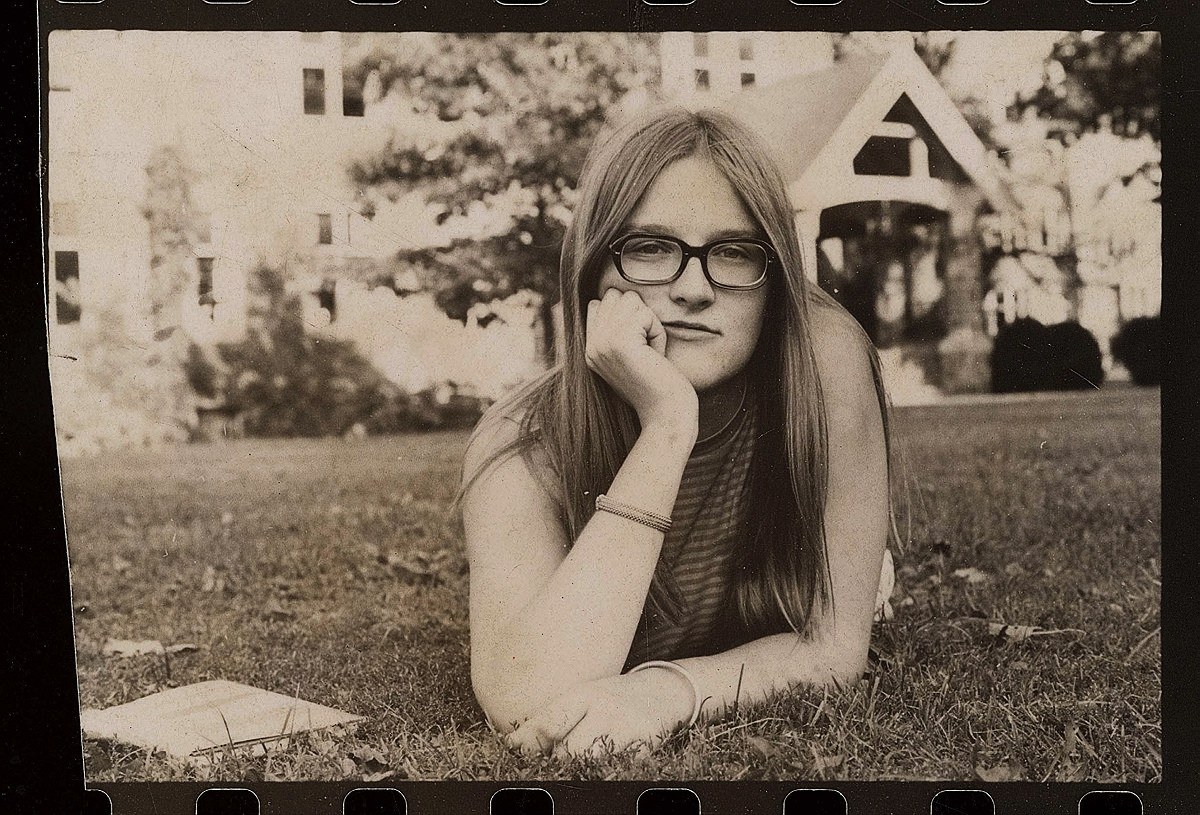

The author at Bryn Mawr, 1967

Photograph courtesy of Drew Gilpin Faust

In 1963, Alabama’s Dallas County Voters League, together with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had begun a voting rights drive in Selma. But it had been stymied by violence, intimidation, arrests, and court injunctions. Selma was a city of about thirty thousand people, 57 percent of whom were Black. Fewer than 1 percent of the city’s eligible African American population was registered to vote, and Selma was notorious for the violence of its response to any Black assertiveness or demands for change. Sheriff Jim Clark—close to a caricature but all too real in his beefy menace—led a posse of law enforcement officers who used nightsticks, whips, and cattle prods to impose what they called “public safety,” by dispersing civil rights meetings, beating Black leaders, and pummeling picketers and protesters. When these tactics seemed only to strengthen the burgeoning Selma movement, national civil rights leaders recognized an opportunity for a battle over access to the vote that could draw widespread attention and support. Selma’s activists formally invited Martin Luther King Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to join their campaign. They were correct in their assessment: as soon as King joined their efforts, Selma began to appear on the front pages across the country nearly every day. I, and many thousands like me, were caught up by the drama.

King arrived on January 2, 1965, to address a crowd 700 strong gathered at Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church to celebrate the 102nd anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. “Today marks the beginning,” King declared, “of a determined, organized, mobilized campaign to get the right to vote everywhere in Alabama.”In the weeks that followed, several thousand African Americans seeking to register were arrested, including King himself. After law enforcement officers violently broke up a march in mid-February, a young Black protester, Jimmie Lee Jackson, was killed by a state trooper, who also brutally beat his 80-year-old grandfather.

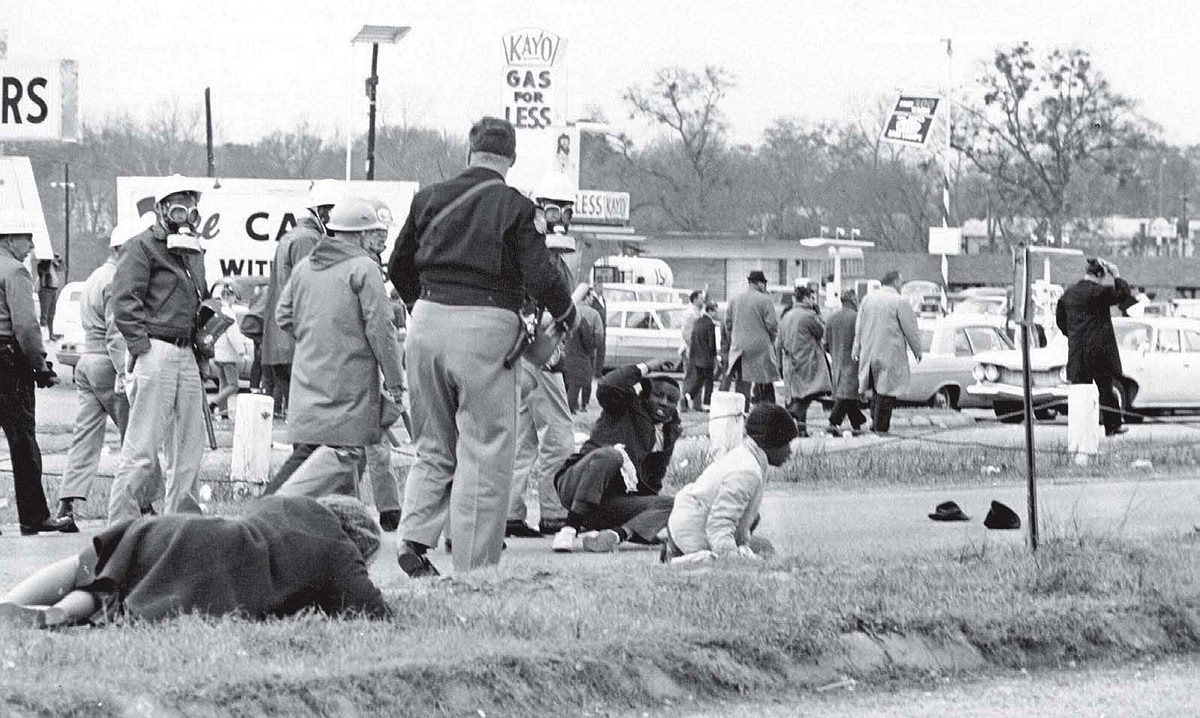

The time had come, James Bevel of the SCLC proclaimed, “to do something dramatic.” King would lead a 54-mile march from Selma to the state capitol at Montgomery. Alabama’s bombastic segregationist governor, George Wallace, vowed he would never permit it to happen. Bloody Sunday was the result, and it received all the national attention the march’s organizers could have hoped for. As the protesters, led by John Lewis of SNCC and Hosea Williams of the SCLC, advanced peacefully over Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge on the afternoon of March 7, they encountered a wall of uniformed men, armed with rifles, pistols, clubs, and whips, as well as hoses wrapped in barbed wire. Many of the troopers were mounted on horses, and many wore helmets bearing Confederate symbols. When the demonstrators did not immediately obey an order to turn around, the police advanced into the crowd, swinging their weapons at anyone and everyone in their path. The marchers tried to flee, stumbling over those who had been beaten and wounded. But police continued to pursue them, donning masks to cover their faces as clouds of tear gas enveloped the scene. They had come prepared not just to stop the marchers but to punish them.

Photographers rushed films of the bloody scene to their networks.

Photographers rushed films of the chaotic and bloody scene to their networks. In those days, news film for television had first to be developed, then placed in canisters to be flown to network headquarters in New York. CBS and ABC showed short clips on the 6:00 p.m. news, but by 9:00 p.m., ABC was ready to broadcast an entire 15-minute segment. It had no narration, which had the effect of inserting the viewer directly into the unmediated chaos. The unforgettable images of Alabama state troopers, mounted on horses, wielding billy clubs against helpless demonstrators have since become iconic. But as I watched on television, it was all too shocking and all too real.

Bloody Sunday: the March 7 march, intended to go from Selma to Montgomery, derailed by horrific state police attacks on the nonviolent protestors

Photograph by the Associated Press/File Photo

From that moment, I knew I had to do something. If I did not stand up, if I did not act after witnessing this, I would be ashamed forever. What more clear-cut confrontation of good and evil could one imagine? What more urgent obligation of American citizenship and basic morality than not just to speak but to act against what had happened on that bridge? All Americans, King declared, “are involved in the sorrow that rises from Selma to contaminate every crevice of our national life.”I knew it didn’t matter to the world at large what I did; I had no illusions that whatever action I took or did not take would have a significant impact on the fate of the Voting Rights Bill. This was an issue between me and my conscience about what was necessary for me to live my life.

Two days after Bloody Sunday, James Reeb, a Unitarian minister from Boston who had come to join the protests, was attacked and beaten by the Klan. On March 11, he died of his injuries, provoking further outrage across the nation—a level of indignation on behalf of a white victim, many Black activists noted, that had not been expressed over the earlier death of Jimmie Lee Jackson. SNCC, CORE, and other groups organized protests in more than 80 cities, including a noisy and disruptive demonstration outside the White House. Though President Johnson declared that he would not be forced into action, pressure to deliver a Voting Rights Bill and to protect demonstrators was mounting. And, as I closely followed the news from Selma and across the nation, I felt increasing urgency about what I should and would do.

On March 17, a Wednesday, an order issued by the federal district judge Frank Johnson paved the way for another attempt by protesters to make the journey from Selma to Montgomery. The march was scheduled for the following Sunday. King put out a call for “all of our friends of goodwill across the nation to join with us in this gigantic witness to the fulfillment of democracy.” I knew I was going to go, and I needed to quickly figure out how.

I enlisted my boyfriend, Adam [a pseudonym],to come with me; together, we persuaded his roommate to lend us his car, a blue Ford Falcon station wagon with room for one of us to sleep while the other drove. I entreated my best Bryn Mawr friend to type up the extremely rough—handwritten in those days—draft of my English term paper—the freshman capstone project—and submit it for me on the due date. I was also going to need to skip a sociology midterm exam, so I set off to tell my professor why, in the hope he might let me take a makeup.

Professor Eugene Schneider, like many on the Bryn Mawr faculty, had an office in the bowels of the college’s faux-medieval library. Tucked behind the cloisters, just off a graystone hallway, Mr. Schneider sat at his desk almost hidden behind piles of books and papers and the gloom of the pipe smoke that filled the room—a sweet-smelling cloud a world away from the fog of tear gas on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. His first question to me after I told him my plans was to ask if my parents knew I was doing this. My answer was an emphatic no.

I shared nothing of my political views or activities with them. They would disown me, I answered. He raised his eyebrows and puffed a few times on his pipe and then replied that since he believed I would be in danger, he wanted me to call him every 24 hours while I was south of the Mason-Dixon Line. If he didn’t hear from me, he would take action. What action? Call out the cavalry, he said. We never specified what that meant. I suspect he had no idea and assumed he would figure something out in the moment if it became necessary. But he left me highly motivated to prevent the summoning of any cavalry. I readily agreed to call.

The trip to Selma from Philadelphia is about a thousand miles. Adam and I decided we would switch off driving every hundred miles so we could stay alert. We wanted to be scrupulously law-abiding, especially as we got farther south. I was well aware of many instances of police harassing those suspected of being “outsiders” or civil rights activists, and we would be heading into Dixie with Ohio license plates. That also meant that we didn’t want to stay at motels or otherwise draw attention to ourselves, as I was only 17 years old, and Adam could be subjected to various kinds of legal unpleasantness for traveling with a female minor across state lines.

We stopped and regularly changed drivers as we had planned; we played the radio, ate the snacks we had brought along, talked about what might lie ahead, and unspooled our anxieties about whether this march would result in violence like the first. We were about halfway there when the radio announcer reported that President Johnson had decided to federalize the Alabama National Guard to protect the marchers. This made us believe we might survive our adventure.

By the time we got to Atlanta, about a 12-hour drive from Philadelphia, we knew we had to find a way to get some sleep. It was well after midnight, and we were confident we would be able to complete the remaining leg to Selma in time for the start of the march later that day. Where could we stay? I had an idea. From the time I had spent in Atlanta in between stints in Birmingham and Orangeburg the preceding summer, I had a vague notion of how to get around the city. I suggested we go to Morehouse College—a historically Black institution and in my mind a safe haven—and find a parking lot where we could sleep in the car. I remembered the correct exit from the freeway, and we located an empty lot where we parked and quickly fell asleep. But before long, there came an insistent knock on the car window. There stood a Morehouse security guard, displeasure evident on his face. We were on our way to march at Selma, I explained, and needed to get some rest before we went any farther. “Bless you.” He smiled and walked away.

We proceeded early the next morning, refreshed, and arrived in Selma as protesters were gathering at Brown Chapel, the SCLC headquarters and the starting point for the march. We were worried about where to park our borrowed car and about what might be done to it while it sat on the street during our absence. Jim Clark’s posse had frequently targeted the cars of civil rights activists, smashing their windows and tires, then arresting drivers for possessing vehicles in violation of safety regulations. And at many sites of civil rights activity across the South, bombs had been placed in vehicles, as in houses and churches. Aside from choosing a fairly exposed parking spot, there was not much we could do except hope for the best—and trust in the effectiveness of the newly federalized troops charged with keeping peace and order in the town.

As we hurried along the sidewalk toward Brown Chapel, we encountered a pair of guardsmen headed in the opposite direction. I felt a sense of great relief as I saw them and may even have smiled in appreciation of the responsibilities they had assumed for our safety. But as they came alongside us and we passed on the sidewalk, the guardsman nearest me reached over and punched me in the breast. I lost my breath—from surprise and shock as much as from the blow itself. They proceeded down the sidewalk as if nothing had happened; I turned and stood gaping at their backs as they moved away. I wasn’t badly hurt; I just had the wind knocked out of me. But I had received a message: even the president of the United States cannot truly federalize the Alabama National Guard. I was reminded that “Alabama” precedes both “National” and “Guard” in their title. And white Alabama remained unwaveringly committed to the racial status quo. As Governor Wallace had put it in his 1963 inaugural address, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

We squeezed into Brown Chapel and found ourselves in the midst of a mass meeting very like the one I had attended in Birmingham the summer before. But the excitement of this crowd was electric as it swayed in time to the familiar anthems of the movement, although many of the words were specific to the place and occasion:

Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me ’round

Turn me ’round, turn me ’round.

Ain’t gonna let no tear gas turn me ’round…

Ain’t gonna let no horses turn me ’round…

Ain’t gonna let George Wallace turn me ’round…

Gonna keep on a-walking, keep on a-talking

Marchin’ up to freedom land.

It seemed a bit like a pep rally in its joyous exuberance, but at the same time, there was apprehension about what might lie ahead. We were troops—albeit nonviolent ones—readying for battle, a band of brothers (and sisters), a happy few, exhorted by our own King to marshal our courage for the fight.

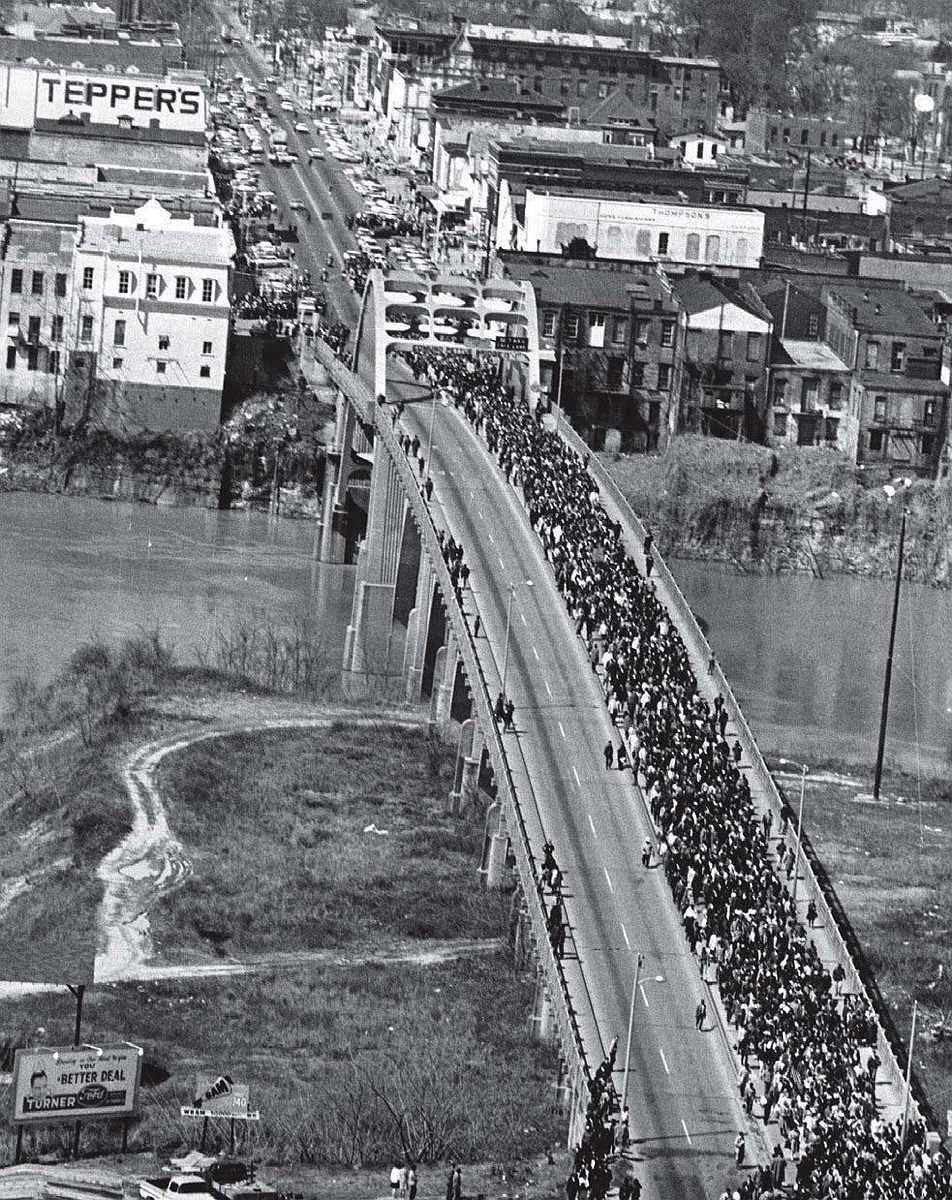

With federal protection, the March 21, 1965, march proceeded, as civil rights advocates crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge en route to Montgomery.

Photograph by the Associated Press/File Photo

The marchers poured out of Brown Chapel and snaked through Selma’s streets toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge. I could see its arches above the heads of the crowd, and soon I was walking up its steep incline. I reached the highest point on the bridge and looked down. Instead of the menacing wall of uniformed troopers I had seen on television two weeks before, determined to halt the marchers at the bridge’s end, National Guard members lined the road on either side, ensuring that the crush of onlookers did not block our way. Thirty-six hundred strong, we were a-walkin’ and a-talkin’ on our way to Montgomery and freedom land.

We marched seven miles that day. Clots of people lined the road. Many were well-wishers—Black residents of Dallas County shouting encouragement and appreciation. I recall numbers of them as either quite elderly or very young. Perhaps they were unable to march but glad to cheer. There were white detractors, too, who shouted hostile epithets and carried signs supporting segregation and urging outside agitators to return from whence we came. I worried that there might be snipers on the tops of the buildings we passed, but the heavy law enforcement presence had accomplished its purpose. Johnson had not just federalized the Alabama National Guard but also sent one hundred FBI agents and U.S. marshals, one thousand military policemen, and two thousand U.S. Army troops, as well as an assistant attorney general to accompany us.I had no notion of the number and variety of our protectors, but there were enough of them in evidence to give me confidence as we walked.

Adam and I were in the middle of the procession, able to see neither its beginning, where the dignitaries and civil rights leaders marched, nor its end. The people walking beside us were a combination of local Black citizens and visitors, like us, who had come south to join the effort. Ministers, teachers, ordinary people who had stories much like ours, they had watched the violence on TV and decided they had to come—for conscience, for America, for justice, and, often, for God. We marveled that we were there; we marveled that this was happening; we marveled at both the support and the opposition we witnessed along the way.

When Judge Johnson had ruled that the march could proceed, he had included a safety provision that had direct relevance for us. After the first day, Route 80 narrowed from a four-lane to a two-lane high way. At that time, and until the road opened up to four lanes again as it entered Montgomery County more than 20 miles later, only 300 marchers were permitted. These would, of course, be the individuals at the heart of the Selma movement, as well as the national leaders who had come to participate. It would not be until Wednesday afternoon that others would be able to rejoin the march for the triumphant entrance into Alabama’s capital city.

The continuing marchers would spend the night in a field close to the designated route. Two local Black farm owners, David and Rosa Bell Hall, had overcome considerable fear of retribution to offer the use of their land as a campground. When we arrived, volunteers were spreading out blankets, singing as they worked. With the fading light of an Alabama early spring day, it seemed to me a pastoral setting far removed from the fears and threats of violence that had surrounded us. We were directed to an area where other volunteers were assigning protesters to buses and cars for the return to Selma. There were also families offering to take marchers into their homes for the night. Suddenly I remembered I had not called Mr. Schneider for more than 24 hours. I had no phone or access to one. Not knowing what to do, I turned to a local woman I had been walking near during the day and asked if she would be willing to make a collect call on my behalf when she got home. She readily agreed, and Mr. Schneider received a mysterious call later that evening assuring him of my well-being. I was grateful he accepted the charges.

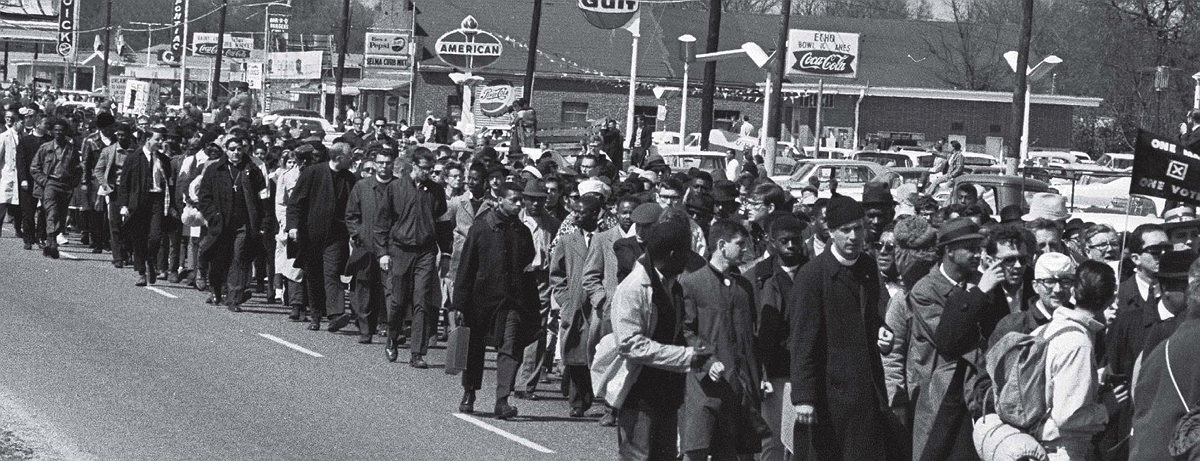

On the road on March 21, beginning the long walk to Alabama’s capital city—and passage of the Voting Rights Act

Photograph by William Lovelace/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty

The couple who took us into their small and tidy house were elderly—at least to my 17-year-old eyes—and had long memories of the constraints and oppressions with which Black Alabamians had lived. They showed us to a well-appointed room—I suspect it was their own—where we collapsed from the exhaustion of a day that had begun in Atlanta so many hours before. When we had learned we would not be able to march again until at least Wednesday, we had decided to return north, as we had no idea where we could stay or how we would occupy ourselves for three days without becoming a burden to others like our generous hosts. In the morning, we were offered a ride back to downtown Selma and, we hoped, our car. The blue Falcon was where we left it, seemingly untouched, though we had a moment of fear about a possible explosion as we turned on the engine. But soon we were under way, feeling safer than we probably should have. Just four days later, at the end of the march, Klan members shot and killed Viola Liuzzo, a 39-year-old white woman who had come from Michigan to participate, as she drove away from Montgomery.

I remember nothing of the trip home. Soon I was back at Bryn Mawr, which had not changed a bit during the four momentous days I had been gone. Its quiet seemed surreal after the intensity of what I had experienced. But I soon received reminders that I had been gone as I confronted the havoc caused by my academic derelictions. My English paper—which my friend had indeed typed and submitted, but which I had never even seen—was returned to me covered with scribbled corrections and outraged comments. My professor, Robert Patten, minced no words about one outcome of my trip:

While sympathizing as a person with your decision to involve yourself in Selma rather than staying at Bryn Mawr to proof-read your paper, as a teacher I cannot help deploring the effect on the paper that decision all too evidently had. The final version is characterized throughout by a degree of sloppiness and laxity that has never before been prominent in your work. This is all the more to be regretted, since you have the insight to have made this a really first-rate study of Camus’ fiction. To begin with, the writing is consistently flaccid. You employ far too many imprecise formulations; there is too much bad jargon and shorthand…A certain imprecision in structure has led to two other flaws: paragraphs are not crisply determined, and ideas and phrases are repeated far too often.

On and on for several typed single-spaced pages.

Since kindergarten, I had strived to be a perfect student, but I received this chastisement with a certain satisfaction. I knew Mr. Patten was right. The paper was a mess. But I secretly wondered what Albert Camus, its subject, might have thought of the whole episode. I had originally chosen my topic and envisioned my paper as a sort of homage to him, but going to Selma was a far better one. We must live our lives, Camus had urged, so as not to be on the side of the executioners. That was the side I had been born on, the one I was struggling to escape.

I thought of the many remarkable people I had encountered in Selma and the risks they took every day in pursuit of freedom and equality. The couple who permitted marchers to camp on their farm; the husband and wife who had welcomed us into their house; the thousands of marchers who had been in the fight for months, years, and even decades, their lives perpetually in danger. The sacrifice of my freshman English paper was the very least I could do. I knew I had not made much of a contribution to the civil rights cause, but I had done something important for myself. For me, going to Selma was an affirmation that some things matter more than others in life. And some things are bigger than any one of us. I had gone to Selma, as Dr. King had requested, to bear witness.

The movement was coming apart, even as I walked down Highway 80…

I had idealized the civil rights movement even before my trip, and my reverence was only strengthened by my days in Selma. It was a thrill when the Voting Rights Act we had marched for became law the following August. But the movement was coming apart, even as I walked down Highway 80.…

Selma was in many ways the end of a chapter. What the progressive social critic Marcus Raskin once called “the We Shall Overcome period of American life” seemed to be over. Even though opening the rolls to Black voters would ultimately transform American politics, activists like Stokely Carmichael did not believe conventional measures could produce the deeper change they sought. The script for my morality play was being abandoned, and it was no longer clear where a white person could fit in with the movement’s changing directions. There was no inspiring demonstration for me to attend, no organization to join, no specific piece of legislation to champion.

It may be that moral clarity inevitably becomes more elusive as one ages. Perhaps my generation understood this when we warned that you should never trust anyone over 30. But even for Dr. King himself, the path forward became more difficult and less obvious. And the emerging tragedy of Vietnam would only make it more so. The first American combat troops arrived in Vietnam on March 8, 1965, the day after Bloody Sunday.