‘‘Everyday Briefs for the Everyday Hero.” This advertising tagline for incontinence underwear won an industry award, making it Seth Taranoff’s greatest achievement, one he is certain is the first step toward life as an agency partner with perks, pay raises, and power.

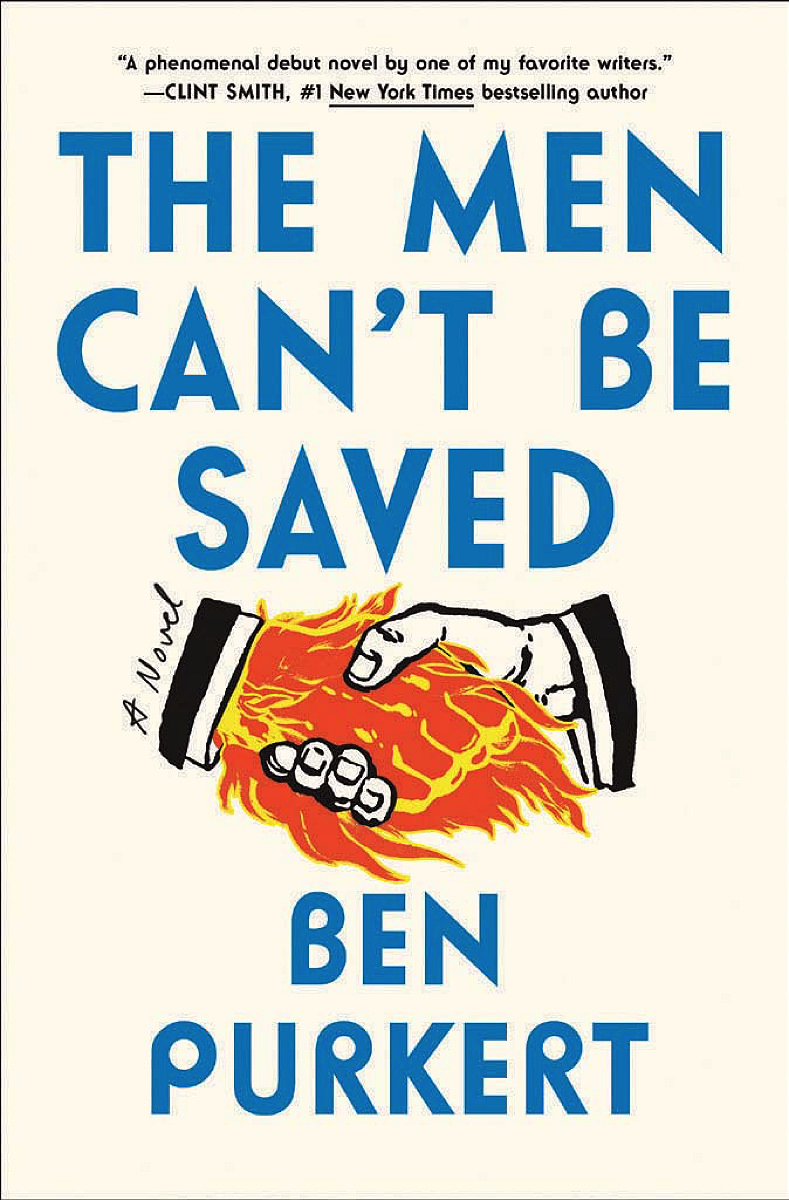

If you’re not particularly impressed with this bit of doggerel, you’re not alone. In Ben Purkert’s debut novel, The Men Can’t Be Saved, published in August, Seth floats along on delusional masculinity—his privilege propels him through his days and nights, his work and his relationships, while he remains remarkably oblivious to how others view him. He thinks himself a good guy, superior to his actual superior at work, Moon, whose boorish frat-boy behavior conjures the more traditional image of toxic masculinity. In Seth’s own mind, “he’s a savant,” says Purkert ‘07, “but the fact that he really can’t see himself is part of why he’s utterly disposable at work and in his relationships.”

When Purkert began the novel a decade ago, he started with a character, not a sociocultural agenda. After writing poetry as an English concentrator, he found a job as an agency copywriter. He was grateful for a paycheck during the Great Recession and loved playing with words, but found the work “soul crushing,” he says. “It didn’t feel like a tagline was a mini-poem, so making art in the service of selling a product felt like a really big compromise.”

In his novel’s first draft, Seth shared that ambivalence, but altering the character’s worldview gave the plot momentum and sharpened the thematic focus. “I’m interested in masculinity and to what extent men are willing to look at themselves and see where they are weak and see where they are strong and be open and vulnerable about that,” Purkert adds before noting that “the very fact I’m saying ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ shows how masculinity is so baked in.”

Overrating his skills on all fronts leads Seth to lose both his job and the woman at work with whom he was having a desultory affair. He lands a barista job and finds a girlfriend who feeds him an assortment of pills he blindly takes to please her; after she dumps him and heads to rehab, he spirals further, becoming a semi-homeless, pill-addicted stalker. “It’s not satire, but there are satirical aspects,” Purkert says. Seth’s obtuseness seemed outlandish when he started writing, but “that was before Trump was in the White House, and #MeToo. Delusional and toxic men have only become more current.”

The women his protagonist spends time with are mostly clear-eyed realists. “Seth has the privilege and option of being ignorant and naïve, while the women he knows do not,” Purkert says. “A lot of the wisdom in the book lives with the women.”

The novel follows his 2018 poetry collection, For the Love of Endings, published a few years after Purkert returned to school (at New York University) for an M.F.A. The poems are tightly wound and darkly beautiful; like unexploded bombs, wrote Jess Smith in The Kenyon Review, carrying a “unique, unsettling mix of clarity and dread.” Shifting from poetry to fiction wasn’t easy. But Purkert’s ability to do so didn’t surprise Boylston professor of oratory and rhetoric Jorie Graham, who taught him poetry. “For a poet to become a novelist, they have to be interested in syntax as a current that runs through a wire that can transmit emotion but also have compassion and curiosity about people,” she says. “Ben always had those capacities.”

Poet Jay Deshpande ’06, who met Purkert in their first undergraduate poetry workshop, says that compassion and curiosity set him apart. “And in the first class, Ben said he was contemplating whether a poem can have a thesis, so he was asking questions other people don’t.”

Purkert, who grew up in suburban New Jersey and now teaches creative writing at Rutgers University, is more modest about his early days at Harvard. “I always wanted to be a writer, but while the vast majority of writers were voracious readers as kids, I’m embarrassed to say that wasn’t me,” he recalls. “I was a terrible writer until I became a reader. That didn’t really start until college, when I was around these students who had such a deep knowledge base, and not just about the books on the syllabus.”

He wrote his first draft at breakneck speed. “It’s easy to do if you don’t know what you’re doing,” he says.

He began with poetry because his interest lay less in plot and character than in language. “Poetry seemed like the genre for people who loved words more than anything,” he says. A course taught by literary critic James Wood broadened his horizons. “He was a real close reader and would spend an hour on a paragraph of a story,” Purkert says, adding, “I loved that. I owe him a lot in terms of making this move across genres.”

Switching to fiction required mapping out a plot. So he approached his novel like E.L. Doctorow, who said, “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” He wrote his first draft at breakneck speed. “It’s easy to do if you don’t know what you’re doing,” he says. Still, he thought it was terrific “and would be published tomorrow.” He spent years learning the truth: “It took lots of turns of the crank.”

In the end, those turns of the crank—and the time they took—changed his writing in ways he hadn’t expected. Purkert grew up in an interfaith home, and for the novel, he deepened his exploration of Seth’s Jewish identity. The author’s relationship to religion, like his relationship to advertising and reality, differs from his protagonist’s, and over the years the gap grew wider. “He was always the same age, but I was getting older and there’s a danger there,” Purkert says. “I have less in common every day with this character, but it doesn’t make Seth’s reality any less important or valid,” he adds. “I always strived, like an actor, to maintain a faithfulness to his voice.”