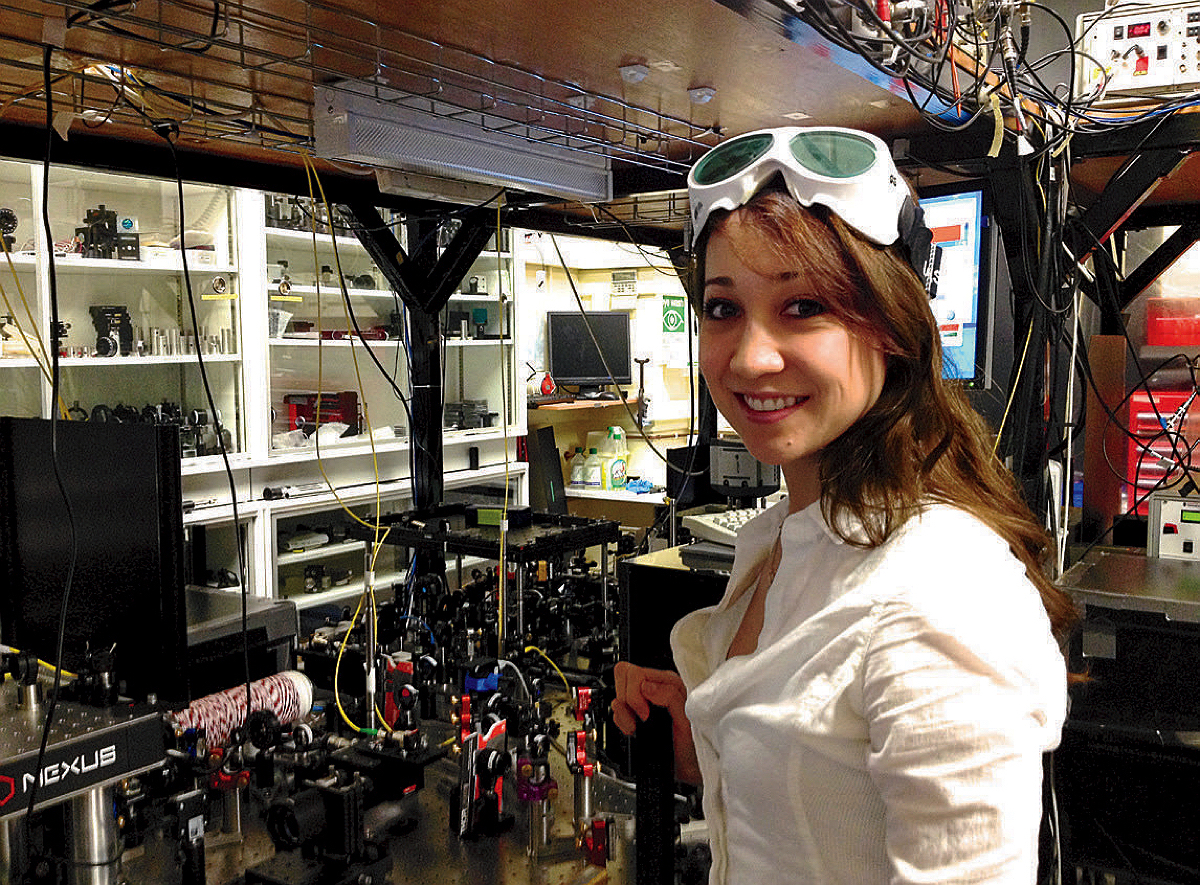

In the fall of 2009, between matinée and evening performances in The Nutcracker at the Boston Opera House, Merritt Moore ’11 would decompress in the basement of Harvard’s Jefferson Laboratory. “I’d take off the tutu and the pointe shoes and the crown, jump in a cab, get to the cleanroom, and put on a full body suit with the glasses and the gloves,” she says. Though she’d taken the semester off from her studies to perform with the Boston Ballet, where daily rehearsals could take eight hours or longer, she’d decided to continue her research with Charles Marcus, then a Harvard physics professor.

They spent the semester working on condensed matter experiments. After her evening Nutcracker performances, Moore returned to the laboratory to monitor the pressure of the vacuum chamber, doing stretches as she waited—often until one or two in the morning. “And then,” she says, “the security guards at the end of the month were like, ‘You know we have CCTV, right?’”

Moore has become used to this kind of multitasking. As an undergraduate, she worked on problem sets on her dorm room floor while doing splits. On school breaks and long weekends, she brought her textbooks on cross-country flights to audition for professional dance companies. While pursuing doctoral work in atomic and laser physics at the University of Oxford, she commuted two hours to London every weekend to train in ballet, doing seated ab exercises on the bus.

Fifteen years after her first appearance with the Boston Ballet, Moore is back with the company, rehearsing for performances of Raymonda and Cinderella while teaching creative robotics at NYU Abu Dhabi. “A lot of times people ask, ‘When do you get rest?’” Moore says. She’s speaking during a break from rehearsals, outside a dance studio, in a black Boston Ballet zip-up. “I think the beauty of it is that [ballet and physics] are quite different. So doing one is rest from the other.”

Lately, though, Moore has looked for ways to bring the two together. After she earned her Ph.D. in 2019, she had to choose between research or dance. She chose the latter, but a thought kept recurring: “Why not both?” After performing with the Norwegian National Ballet, she asked the company Universal Robotics if it were interested in a collaboration. It sent her a robot: three rods connected by joints that can swivel and bend, usually used in manufacturing applications.

Working with the robot, Moore found that its movement “inspired movement in me,” she says. The reverse was also true: using the robot to mimic the gestures of a human body created motions compelling in their own way. As the first artist-in-residence at Harvard’s ArtLab, she began to choreograph “duets.” In these works, Moore’s dancing is fluid and expressive, her arms and back often slithering gradually into shapes rather than forming them all at once—mirroring the maneuvers of the robot’s swiveling rods.

Moore posted her performances online and found that they resonated with audiences around the world, especially during the pandemic, when dancers couldn’t rehearse and perform with human partners. Today, she performs with the robot at venues as diverse as the Boston Ballet, the World Economic Forum, and Harvard’s Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence.

Moore has been using science and dance to connect with the world since childhood. Growing up in Los Angeles, she never found language an intuitive way of expressing herself; she didn’t speak until she was three. But math made sense: “I really liked patterns,” she says, “and I loved puzzles.” Later, in high school, physics offered a way to use math to answer concrete questions, she says, “to explore all the unknowns of the universe.”

Dancing, too, offered a nonverbal means of communication. Moore started ballet at 13, when her mother enrolled her in classes to improve her posture. She was “immediately hooked”—but she had started late, and she found herself behind her classmates. “I was always the worst one in the class,” she says. While auditioning for professional dance companies, “I would see new stuff for the first time and think, ‘Oh, OK, we’re going to learn this here.’”

At the end of high school, Moore auditioned for ballet schools but wasn’t admitted. She gave up her dreams of dancing professionally and devoted herself to physics—a field where her comfort with being the “worst one in the room” served her well. Some classmates in her freshman quantum-mechanics seminar had been studying physics since elementary school. Moore had taken her first physics class only the year before. But her interest motivated her to stay in the class: “This is real-life magic,” she remembers thinking.

Meanwhile, Moore kept dancing. She joined the Harvard Ballet Company, where she was able to perform frequently—an experience not possible at ballet schools, where more time is spent perfecting technique. Dancing for audiences of busy students helped her to focus on expression, sometimes breaking the conventions of ballet to convey something deeper. “[The people in the audience] aren’t here to critique my turnout; they’re here to have a good time,” Moore recalls telling herself before performances. “I can’t overthink things anymore. I just have to give.”

At Harvard, Moore started auditioning for professional companies—more for the learning experience than any expectation. But her sophomore year, she was accepted to the Zurich National Ballet. Thus began her zigzag career path, as she took time off from her studies to dance professionally.

Through her recent work with the robot, Moore hopes she’s found a way to pursue science and dance simultaneously. She’s exploring the use of artificial intelligence to help make the performances more interactive: “If I make a gesture,” Moore asks, “how can we teach the robot to make a gesture in response?” To achieve this, she wears a motion-capture suit and turns her dance moves into a series of data points. In the same way that large language models like ChatGPT learn from vast amounts of text data, the robot can learn from Moore’s movements to create its own choreography.

She hopes to eventually return to quantum physics, possibly exploring the intersection between quantum computers and AI—work in which dance will likely remain a part of the equation. “I’ve been trying to quit ballet for over 15 years,” Moore says. “The number of times I’ve quit and thought, ‘Okay, I’m done. I’m now going to be a good scientist, a good academic. I’m quitting. I’m burning the shoes.’ And I’m still here.”