Harvard celebrated the launch of the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence on Thursday afternoon with a whirlwind of performance art, presentations, and panel discussions centered on the institute’s mission: elucidating the fundamental principles that underlie human and machine intelligence.

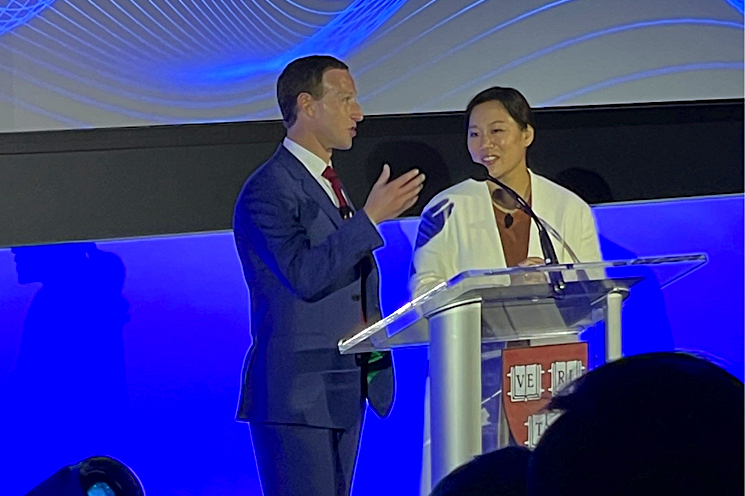

Priscilla Chan ’07 and Mark Zuckerberg ’06, LL.D. ’17 (Facebook, now Meta Platforms, cofounder, chairman, and CEO), whose Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) pledged $500 million to create the institute in December 2021, shared their vision for the new enterprise. President Lawrence S. Bacow spoke about how far artificial intelligence (AI) has advanced since he was a freshman at MIT, and University provost Alan Garber described how students catalyze the interdisciplinary collaborations among faculty that develop the next generation of leaders in new fields. There were even prerecorded well-wishes from business leaders who have shaped the new economy—Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates ’77, LL.D. ’07; Eric Schmidt, former CEO and chairman of Google; and Andy Jassy ’90, M.B.A.’97, president and CEO of Amazon—suggesting the portent of the moment. As Jassy put it, “in the future, almost every application that any of us use will be using AI in some meaningful way.”

Mark Zuckerberg ’06, LL.D. ’17, and Priscilla Chan ’07

Photograph by JS/Harvard Magazine

The co-directors, Moorhead professor of neurobiology Bernardo Sabatini (who noted that it is now possible to not only “watch the brain in action,” but to “literally write patterns of activity into the brain”) and McKay professor of computer science and professor of statistics Sham Kakade, shared their goals for the Kempner Institute, while Stanford professor Stephen Quake, the CZI’s head of science, put those aims in a larger context, as he outlined its mission of curing, preventing, or managing all diseases by the end of the century. Recorded remarks from the deans of Harvard Medical School, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences emphasized the power of interdisciplinary research, while video messages from eminent cognition scientists suggested how much there is to learn about both human and machine intelligence. Nelson professor of biomedical informatics Isaac Kohane explained how artificial intelligence (AI) can improve the field of medicine; and two panel discussions among researchers from Harvard and other institutions focused on the tremendous potential of scientific investigations at the intersection of natural and artificial intelligence.

Kempner Institute co-directors Sham Kakade and Bernado Sabatini

Photograph by JS/Harvard Magazine

Setting the tone for the afternoon symposium—held in Winokur Family Hall, the largest of the lecture halls in the Science and Engineering Complex in Allston (see “A 500-Year Building”) where the Kempner Institute will be housed—was a dance choreographed by ballerina and quantum physicist Merritt Moore ’10, who performed with the Boston Ballet’s Tyson Ali Clark, flanked by two gracefully motile industrial robotic arms.

Bacow thanked Moore and Clark for their artistic interpretation of how humans can interact with machines. Then, in humorous introductory remarks, he drew on his own experience to illustrate how far machine intelligence has come since he was a student. In 1968, as a junior in high school, he recalled, he was very much taken by Arthur C. Clarke’s science fiction story about a computer, Hal, that managed all the systems on a spaceship, and by the film adaption, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. “That was my introduction to artificial intelligence. And of course, if you know the movie, you know the story of how it sort of went off the rails. Really interesting—but we’re not going to go there.”

Still photo from a dance performed by Merritt Moore ’10 and Boston Ballet dancer Tyson Ali Clark, in partnership with composer Nick Jones and the Harvard University ArtLab.

Photograph by JS/Harvard Magazine

As a student at MIT, Bacow was introduced by a classmate to one of the earliest interactive computer programs, designed to probe how a person was feeling that day; and later, when he was chair of the faculty at MIT, he was astonished by a demonstration of a robot that could catch a softball, a computationally sophisticated innovation that was nevertheless “something that any four-year-old can do.” Now, he said, “Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg have given us” an incredible opportunity “to imagine taking what we know about the brain and about neuroscience, and taking what we know about how to model intelligence,” to put them together in ways that can inform both, “in order to advance our understanding of intelligence from multiple perspectives.”

The Zuckerberg and Chan Perspectives

Chan and Zuckerberg, who were reportedly deeply involved in the planning of the Kempner Institute, spoke about how their backgrounds have shaped their philanthropy. Zuckerberg recalled reading the newspaper as a child, encouraged by his grandparents to sharpen his mind, and said the institute bears his mother’s and grandparents’ name to honor their focus on “the power of the mind and intelligence to try to improve the world.” Chan, a pediatrician who has founded several schools, emphasized the importance of her undergraduate education, recalling how the Mind, Brain, and Behavior interfaculty initiative (introduced in 1993) had allowed her to pursue interdisciplinary study. The daughter of Vietnamese refugees from Quincy, she teared up as she described her parents’ 18-hour workdays running a restaurant while her grandmother cared for her and her sisters, and how attending Harvard “meant the world to me. But to be able to stand here on this stage and give back,” she said, “is truly a dream come true.”

Zuckerberg and Chan met as Harvard undergraduates. In 2015, when their first daughter was born, they pledged 99 percent of their equity in Facebook to fund the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which announced the following year an ambitious program to end human disease by the end of the century.

Chan, noting that “every profession is being transformed by AI,” nevertheless emphasized the “huge roadblocks to building better AI that helps people. For one thing, we barely know how these systems work. And we want to help machines make good choices, which is even more complicated” (see the feature article “Artificial Intelligence and Ethics” for a discussion of such challenges). Zuckerberg added:

[I]f we can learn more about how the brain works, then we should be able to use that to engineer more intelligent AI systems. And the reverse should also be true. If we can apply machine learning to human biology, then we can learn a lot more about who we are, and how the brain works, and how to keep it healthy when things aren't working the way they’re supposed to. [For example], let’s say that you want to…sequence a million neurons in the brain? It sounds like a lot, but there’s like 86 billion neurons. So it’s not that big of a cross section….And then, let’s say that for each of those, you want to study 30,000 different mRNA molecules in each of the cells…a mathematically huge space…that’s not a thing that people can make sense of in their own minds. That’s the type of problem that really is well-suited for machine learning. So, there are all these different kinds of examples of how artificial and natural intelligence [complement] each other, and advances in one are going to help understanding of the other….

Zuckerberg hopes the Kempner Institute will spur cooperation between “cognitive scientists and neurobiologists who study the brain, and mathematicians, statisticians and engineers who study machine learning and AI,” in a way that hasn’t previously occurred at scale. “The institute [will]…give them the tools and the opportunity to take on some new grand challenges together. And the result, if this works out,” he said, “should be a one-of-a-kind institute…that helps us discover what intelligent systems really are, and how they work,” and how to repair them when things go wrong. The broader implication, he added, is that “once you understand how something is supposed to work, and how to repair it once it breaks, then you can apply that to the broader mission” of CZI, “to empower scientists to help cure, prevent, or manage diseases.”

Pillars of the Institute—and Many Questions

In a presentation that followed, Kempner co-directors Bernardo Sabatini, who has been a member of the Medical School faculty since 2001, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator since 2008, and Sham Kakade, who joined the engineering and applied sciences faculty in January, spoke about three of the institute’s guiding principles:

- research, including the creation of better algorithmic design principles;

- education, encompassing the training of the next generation of scientists and researchers in this field and;

- computation, bringing together shared technology and expertise.

Among their near-term research goals is to reveal some of the fundamental mechanisms of biological intelligence; and in the domain of machine learning, to overcome hurdles to the creation of artificial general intelligence (systems that can learn like humans—for instance, by transferring knowledge acquired in one domain and applying it in another). Sabatini touched on the enormous potential of neural prosthetics, enabled by brain-machine interfaces, for alleviating suffering and remedying, for example, paralysis.

What followed was wide-ranging commentary from scientists, a sampling of which follows, some delivered in person, and others via pre-recorded remarks, which raised numerous intriguing questions that the institute might tackle:

Beyond general intelligence are many other seemingly intangible products of the human mind. What underlies inspiration, motivation, and ambition?, asked cofounder and CEO of DeepMusic.ai Carol Reiley. “How do you break human creativity into its fundamental steps?”

Daniel Huttenlocher, dean of MIT’s new Schwarzman College of Computing, added that “…the parts of intelligence that we’ve really been able to formalize don’t, for the most part, include things like emotional intelligence, like good judgment, like split second decisions.”

Even more complex is the intelligence that controls social behavior, pointed out Higgins professor of molecular and cellular biology and Ezpeleta professor of arts and sciences Catherine Dulac, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator who studies the control of instinctive behavior in animals.

Another vivid example of the gap between AI systems and human brains, said Yann LeCun, vice president and chief AI scientist of Meta, and a professor of computer science, data science, neural science, and electrical and computer engineering at New York University’s Tanden School of Engineering, is the fact that “Any teenager can learn to drive a car in about 20 hours of practice, whereas we still don’t have fully autonomous self-driving cars, despite training them for thousands of hours with lots of data from experts and all kinds of techniques. And so obviously, we’re missing something big in terms of the background knowledge that humans can use before they learn new tasks.”

Isaac “Zak” Kohane, inaugural chair of the department of biomedical informatics, explained how AI is already transforming medicine by reducing surgical errors, improving clinical knowledge and decision-making by physicians working with patients, and allowing, for example, a paraplegic who cannot speak to express himself via conversion of brain signals into text on a computer monitor. In another instance Kohane cited, computer-aided analysis of patient health records revealed the characteristic pattern of domestic abuse, a problem that can too easily escape the notice of physicians, even in Massachusetts, where healthcare providers are mandated to ask whether a person feels safe in her or his own home.

Berkman professor of psychology Elizabeth Spelke, who studies cognitive development, said that when her research indicated that very young babies have the ability to distinguish objects, faces, and places, she was initially skeptical that this might be provable. But interdisciplinary approaches, including the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging, supported her findings, and she said, “I started to see that I didn’t need to answer these questions alone, that they can be answered” by “bringing together people from different fields….”

And professor of neurobiology Sandeep Robert Datta, who has developed evidence for a grammar of behavior and is currently studying how the brain processes olfactory information, explained how the ability to analyze massive amounts of high-dimensional data had led to his lab’s surprising discovery of the way that SARS-CoV-2 can disrupt the ability to smell: not by attacking neurons directly, but rather the cells that support them.

In his concluding remarks, Bacow noted that the most important problems confronting society do not respect disciplinary boundaries: “And one of the reasons we’re excited about the Kempner is because it’s going to help us knit together a variety of fields, a variety of disciplines.” He also touched on the importance of collaboration: among faculty and students, across departments and schools, and even institutions. As he noted, “…we sit in the center of the densest concentration of academic talent in the world” contributed by the many institutions in the area. “We draw upon that talent, we exchange students, we work together with colleagues in many of the great universities” and teaching hospitals “that are within just a few miles of here. This is an enormous strength, which allows us to do things that are very, very hard to do in other places in the country.” Another is the University’s prospective investments in computational power, including through its quantum initiative, “which will allow us to do things that we are incapable of doing today.”

And finally, acknowledging the Kempner Institute’s commitment to providing students with the support that will allow them to undertake study that crosses traditional academic boundaries, Bacow emphasized students’ importance to the research enterprise, and to making the world better. At Harvard, he said, “…technology transfer is really called Commencement; it’s when we turn these amazing students out into the world,” whether to pursue careers in academia or industry, to become leaders in “so many different fields, some of which haven’t even been imagined.” He concluded by quoting the reflections of a Talmudic scholar who said, “I’ve learned so much from my teachers, more from my colleagues—but most from my students.”