Editor’s note: Meg Campbell ’74, an educator—she is the retired cofounder of the Codman Academy Charter Public School—lives in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood. She submitted this essay after attending her fiftieth reunion this past spring.

I read Helen Keller’s The Story of My Life in third grade, a Christmas gift from my mother. It was the original, not what my mother called a Reader’s Digest children’s version, which she held in low regard.

My mother came by her book snobbery through her father. He told her, whenever visiting someone’s home, to take note of whether there were books there, and if so, which ones—because the books one owned revealed a person’s character. The gift of the Helen Keller autobiography was part of a long trail of recommended books, usually biographies. Reading about illustrious stars from Marie Curie to Annie Oakley, though, often discouraged me, because the subjects showed great promise at the young age I was: to keep up, I needed to start inventing things like Thomas Edison had. His biography prompted me to concoct an air humidifier by standing under a towel with my head over a pot of boiling water. My mother shooed me out of the kitchen so she could make dinner.

Helen Keller ignited my imagination. She made me grateful I could see and hear. I knew pretending to be blind for a short time was nothing like being without sight; or putting cotton balls in my ears couldn’t come close to making me deaf. I had to think harder, work harder to summon an image—a feeling—of Helen at 19 months losing her sight and hearing.

The likeliest outcome for Helen would have been a life landlocked in her mind. But then young, feisty Anne Sullivan left Boston to teach and live with Helen in Alabama. Helen even went to Radcliffe.

I stopped reading. What is Radcliffe? I went to ask my mother.

She was changing sheets. She looked up, but kept moving, tucking the ends into the side of the mattress and sweeping her hand across the top of the bed to smooth out creases.

“Radcliffe is the best college in the United States for women.”

“Then I’m going there,” I said, and started out of the room, to return to my reading.

She added within earshot, “If you go there, you won’t be making beds the rest of your life.”

When I became a Radcliffe student in 1970, I searched for evidence of Helen Keller’s time at the college. I looked in the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, my favorite setting to study because it was the only place on campus where women’s accomplishments and struggles were studied and celebrated. I discovered the book, Helen Keller: The Socialist Years, which included her advocacy writings. There had been no mention of her political stands in her autobiography. I saw her as more complicated and generous. I admired her even more.

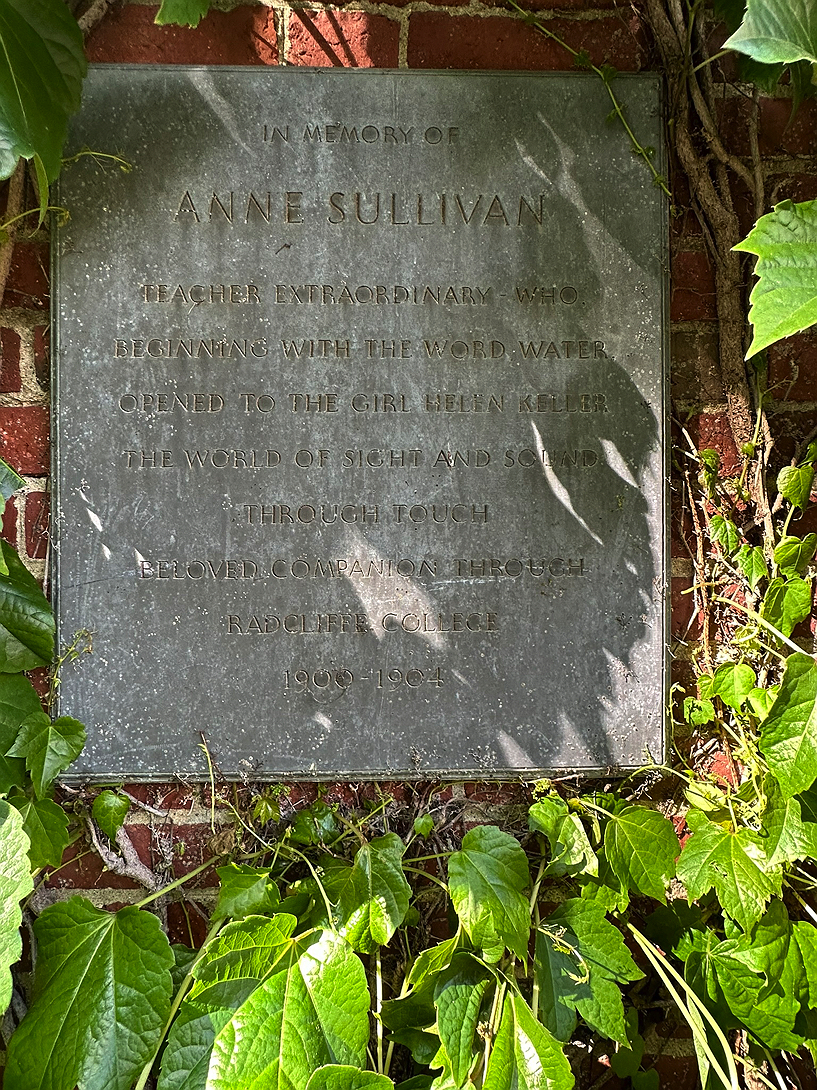

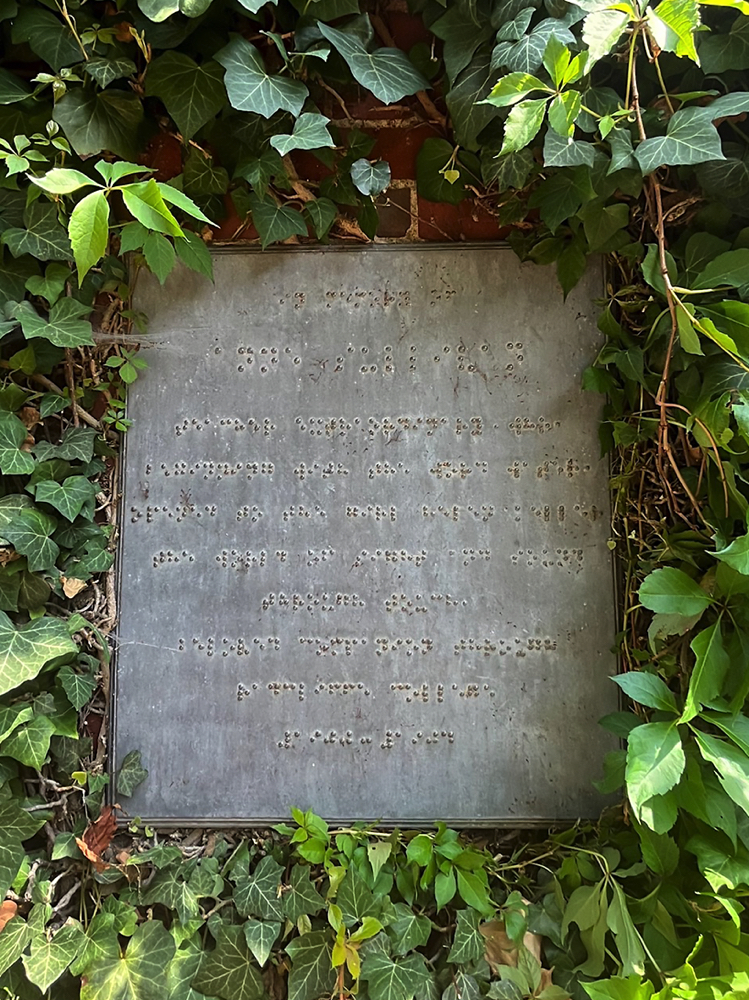

Across the street from the Schlesinger Library is a stately brick building, Cronkite, which was then women graduate students’ housing (and now is the Harvard College admissions office). We undergraduates were allowed to eat in their dining room, and I often did for I relished the genteel atmosphere and floor-to-ceiling paned windows overlooking a beautiful garden. The selection of plantings was made by Helen Keller based on their fragrance, informed by her own strong sense of smell. At one end of the garden Helen included a fountain extending from the brick wall over a half-basin next to a bronze engraved plaque. I liked to listen to the sound of water falling and read the inscription: In memory of Anne Sullivan, Teacher extraordinaire—Who with the word Water, opened to the girl Helen Keller the world of sight and sound through touch. Beloved companion through Radcliffe College, 1900- 1904.

At my recent reunion, I returned to the garden to thank both extraordinary women for influencing my life’s course. Helen’s example continues to challenge my expectations about human possibility in the face of the most daunting disabilities. Anne Sullivan’s gutsy, try-anything experience-based teaching methods have shaped my work and life as an educator. I owe them.

It was a warm day when I reached the garden, which was planted nicely enough, but not in accordance with Helen Keller’s original design focused on scent. The fountain was harder to find because there was no longer water flowing, and ivy covered the plaque.

I yanked vines back to be able to read the inscription. I imagined Helen Keller standing in this spot at the dedication of the Anne Sullivan Memorial Garden on June 11, 1960. Anne had died 24 years earlier, but she had launched Helen on to a global stage of influence. Starting at the age of 34, Anne tapped every word for every Radcliffe class for her pupil’s understanding. This was a feat of love and perseverance culminating in a degree with honors for Helen Keller.

Anne’s brilliance was in her unorthodox, deeply hopeful method. If she were alive now, she would be a MacArthur Foundation “genius” recipient. Harvard should continue to maintain the fountain and fragrance garden. The site and story would enrich admission tours, which begin a stone’s throw away. A posthumous undergraduate degree for Anne Sullivan would be appropriate too—and long overdue.