With stitches as dense as an iPad’s pixels, this woven tunic represents the pinnacle of Inca artistry. The brutal Spanish conquest and the unforgiving march of time have destroyed most Inca textiles, but the tunic now at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., survived. Although its symbols captivate visitors and scholars alike, much is left to be learned about the garment. Who made it? Who wore it? Is it truly authentic?

Robert Bliss, who cofounded Dumbarton Oaks, Harvard’s center for Byzantine, Pre-Columbian, and landscape studies, purchased the tunic for his personal collection, so its acquisition history is not well documented. Added to the institute’s holdings in 1963, the tunic attracted scholarly attention as researchers attempted to decode its symbols, which they believed comprised a written language, despite evidence that the Incas did not write.

Much later, Andrew James Hamilton, Ph.D. ’14, now an associate curator at the Art Institute of Chicago and author of The Royal Inca Tunic: A Biography of an Andean Masterpiece (Princeton), analyzed colonial accounts of Inca life, and learned that this tunic symbolized power. The only weavers allowed to make these symbols (tocapus) were employed by the state, and the Inca emperor redistributed clothes with tocapus to his allies. “They were sort of like a state-controlled fashion statement,” he says. Only the emperor himself could don a garment with all of these tocapus—a way of telling his subjects, “I control you,” Hamilton explains. “My armies brought you all together. I am wearing you physically on my body.”

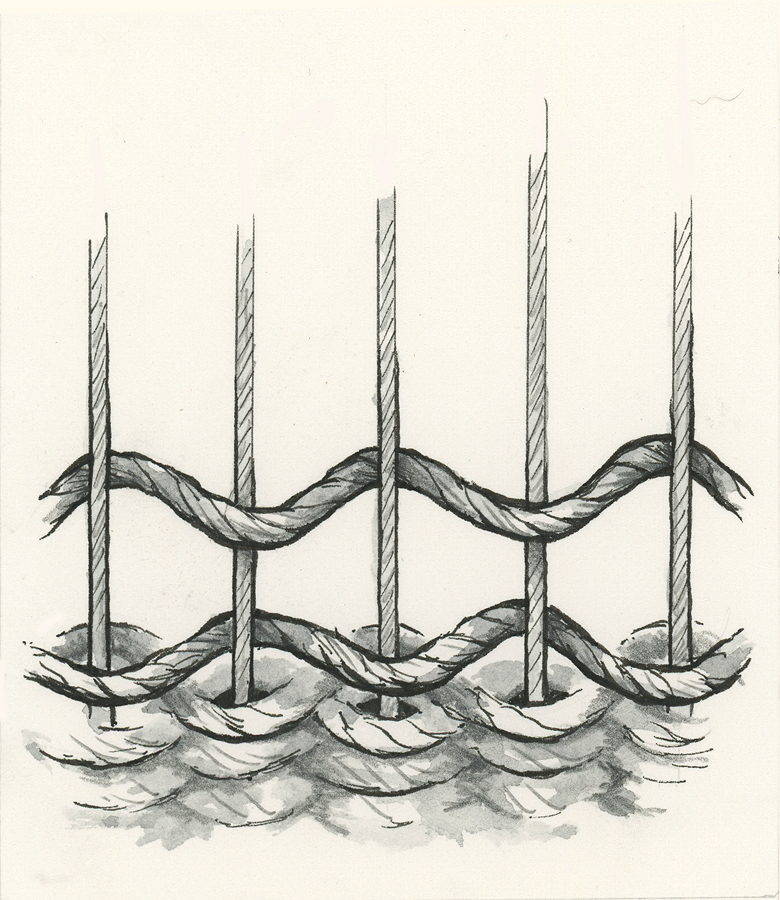

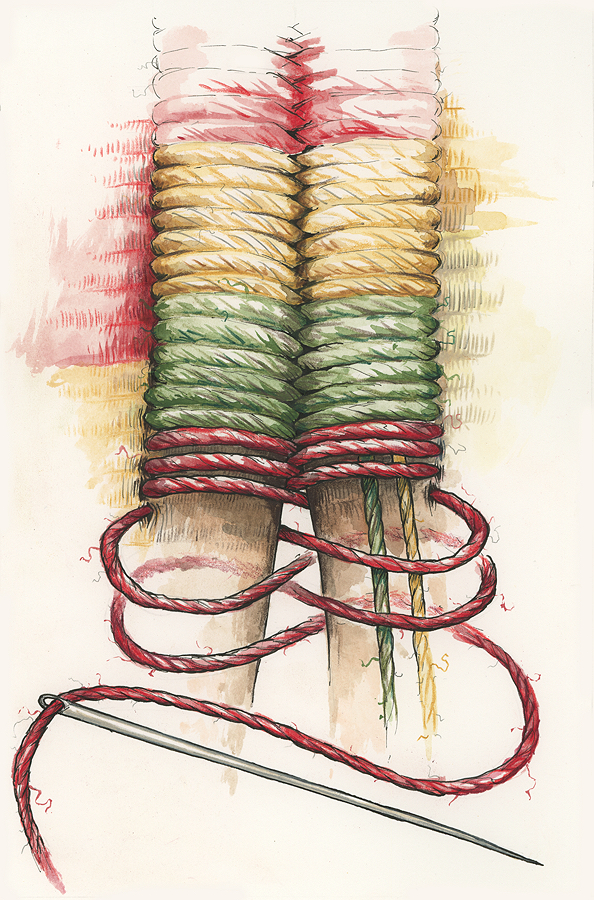

At Dumbarton Oaks, Hamilton in effect reverse-engineered the garment’s creation, learning to weave with similar materials. Analyzing the tocapus, he noticed that one side was more intricate and precise than the other, suggesting that the tunic was created by a pair of female weavers: a student and a master. He also observed needle holes around the edges, evidence of an unfinished zigzag embroidered edge. “There are very few moments in history,” he says, that a tunic “of this stature [could be] left unfinished.” The materials and designs are consistent with pre-contact Inca tunics: it does not employ silk brought by Spanish traders. Accordingly, he estimates the tunic most likely dates to the period of Spanish conquest, 1528-1533, perhaps intended to be worn by Atahualpa, the final Inca emperor.

Following the destruction of the Inca empire, the tunic continued to be worn; the garment was twice torn and repaired. “Even in the colonial period, there were very few people who would have had the social standing to…wear a tunic like this,” he continues.

Hamilton hopes that people will appreciate this tunic for its artistry and its historical significance. “Art history focuses on named makers,” he notes. “There are fewer opportunities for Indigenous artists to be recognized at the level of Picasso and Velázquez. This is a rare opportunity to…see the identities of two weavers from 500 years ago creating this object.”