Disorienting and unexpected, a white room with a checkered carpet is turned sideways: tables are bound to the wall, and the wall lies at viewers’ feet. This room, collapsed and contorted, symbolizes the home within a collapsed East German state.

The installation is part of an exhibition opening today at the Harvard Art Museums. The artwork’s title, Ostalgie, a contraction of the German words for “east” and “nostalgia,” reflects both a longing for home and the complex, fragmented national identity that took hold in Germany in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The artist, Henrike Naumann, was born in Zwickau, East Germany, in 1984 and grew up hearing promises of “secure peace” from Erich Honecker, the country’s leader and Communist Party chief. At that time, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) boasted the highest GDP in the Eastern Bloc. When the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, the five-year old Naumann experienced the unification, at least on paper, of the two halves of Germany—and, as citizens of a sovereign nation, Germans watched the Soviet Union dissolve.

Now living in Berlin, Naumann studied costume and stage design at Dresden’s Academy of Fine Arts and scenography in Potsdam. Her installations often feature second-hand furniture and home accessories sourced online, adding layers of meaning to her work.

Ostalgie is one of the central works in Made in Germany? Art and Identity in a Global Nation, which features artwork made after 1980 and delves into what it means to be German in a country shaped by the history of the Third Reich, socialism, mass migration, and the evolving rise of the far-right and neo-Nazism. The exhibit explores questions of diversity and national identity, and although the artwork is German, the issues resonate strongly with viewers at the Art Museums, as similar themes have come to dominate American public discourse and the 2024 presidential campaign.

The exhibition features sculptures, found objects, installations, drawings, paintings, video art, photography, and mixed media; most of the pieces (including several recent acquisitions) come from the collection of Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum, which is dedicated to the art of German-speaking Europe from the Middle Ages to today. The show was curated by Lynette Roth, the Busch-Reisinger’s Daimler curator, alongside Engelhorn curatorial fellow Peter Murphy, and senior curatorial assistant Bridget Hinz.

Naumann’s Ostalgie is one of the exhibit’s most striking pieces. Part of its inspiration was the 1960s animated series The Flintstones. In the sideways room, animal fur rugs and plastic bones are scattered across an otherwise minimalist space, evoking the cartoon's prehistoric cave setting. Naumann watched The Flintstones on German television growing up—a U.S. import that became embedded in her memories, subtly linking the consumerist, middle-class American family with its imagined roots in a Stone Age past. In Ostalgie, Naumann hints at how Soviet and post-Soviet East Germany was often perceived by external observers as similarly “prehistoric.”

The installation is filled with clues, both subtle and overt, hinting at the influences shaping German identity. Three decades after reunification, Naumann explores how different ideologies all composing one culture manifest in domestic spaces. The home, meant to be a place of comfort and the dissolution of boundaries, becomes a metaphor for the uneasy complexity of German nationhood.

One striking element is a Soviet-era phone with a Viking horn in place of the receiver—a nod to the imagery co-opted by Germany’s contemporary far-right, which resembles the neo-Nordic and “pagan” symbolism adopted by the U.S. QAnon movement (such as the headdress worn by Jacob Chansley, the so-called “QAnon Shaman,” during the storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021). Nearby, a flag hung on the wall features 1950s industrial and agricultural workers—angry “Ossis,” or East Germans—who brandish blood-covered hammers and sickles. In the center of the flag, the communist emblem is encircled by language used by extremist far-right groups. Naumann purchased this flag online from an East German eBay shop: an act of material ethnography, offering a tangible representation of Germany’s politically muddled national narrative.

Post-reunification East Germany grappled with mass unemployment, a reduction in the achievements and status of the individual, seismic labor market shifts, and the erosion of social bonds—issues so alien to West German officials that they were paid an “outback bonus” to explore the territory. Today, these challenges remain woven into the character of the German people. For Naumann, as the other artists in Made in Germany?, understanding the modern German culture requires acknowledging the diverse forces that have shaped it.

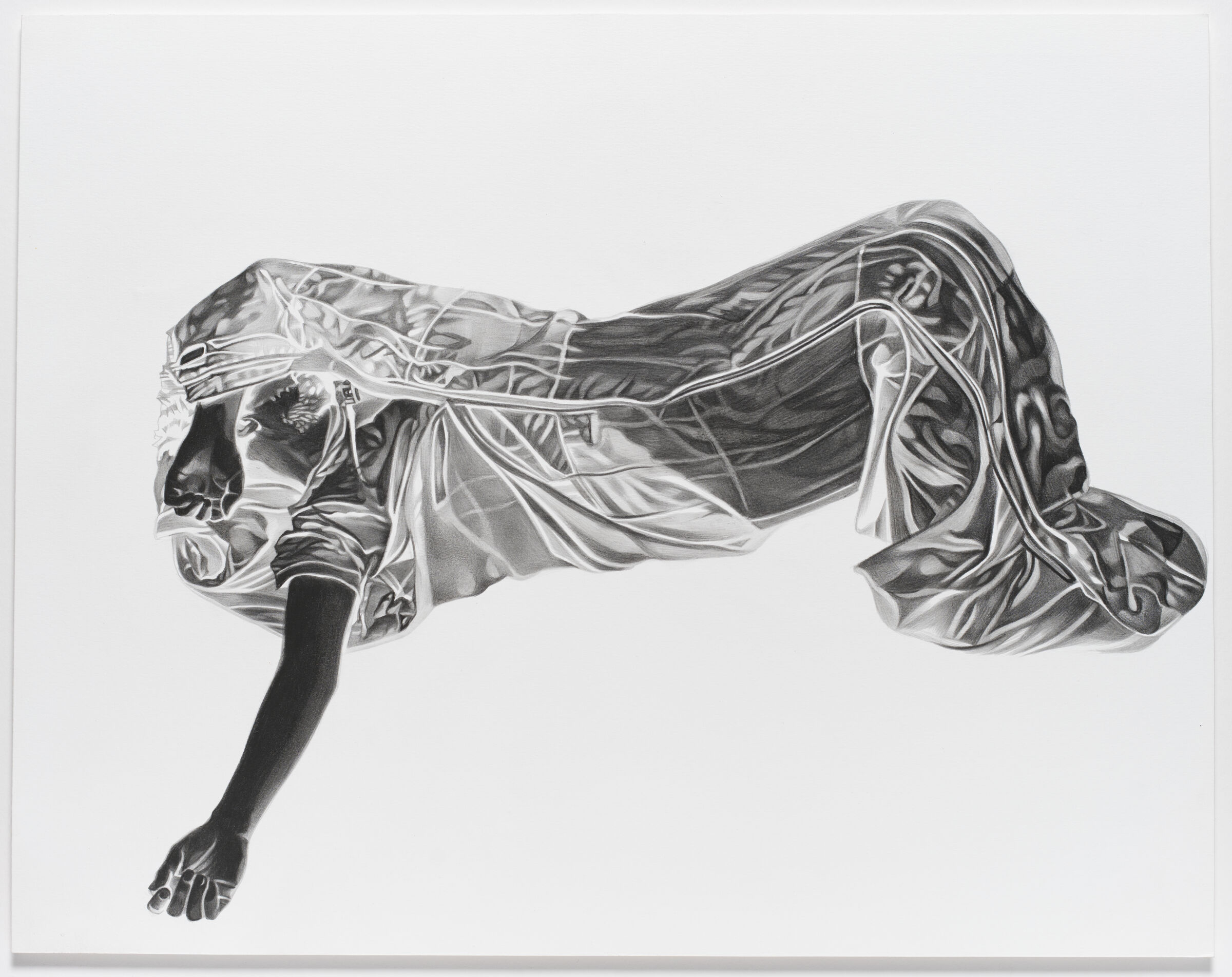

In 2024, Germany continues to contend with the impacts on national identity of migration and the cost of living. Works like Ngozi Schommers’s Commuters (2022), depicting two rolled-up sleeping bags illuminated by a portable light, speaks to the universal inhumanity of the housing crisis. Marc Brandenburg’s three Untitled pieces (2019), drawn in graphite, depict faceless individuals in sleeping bags—an image familiar in cities across the United States, where homelessness is an increasingly urgent national problem.

Throughout the exhibition, mixed media works explore migration, such as in Candida Höfer’s Turks in Germany (1979), a slide projection depicting the migrant population brought to post-war Germany to fill labor shortages. Similarly, Nevin Aladağ’s video project The Family Tezcan (2001) captures a Turkish migrant family grappling with identity in a nation where they are seen as “other.”

As contemporary Germany navigates its role in a globalized world, Made in Germany? serves as both a snapshot and a mirror, inviting audiences to engage with the nation's past, present, and future in its quest for an inclusive identity—and for Americans, perhaps to see the same debates as echoed in this nation’s conversation, on electoral and domestic stages.