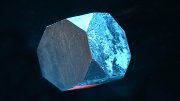

For several decades, Harvard physics professors have shared a small block of uranium with their students. It is a strange

object: although the cube is only 5 centimeters per side, it feels unbelievably heavy and is cold to the touch. But during its use as a lecture prop, its sinister origin story was not emphasized, says Sara Schechner, Wheatland curator emerita of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments (CHSI).

In 1939, as Germany invaded Poland, the Nazi government secretly initiated a nuclear program. Despite this early work, the Germans never managed to sustain or control a nuclear fission chain reaction, the necessary precursor for an atom bomb.

In late 1944, as Allied forces approached, a group of German nuclear physicists working for the Nazi government moved their laboratory to a cave beneath a castle in the small town of Haigerloch. Their final experiment, led by Werner Heisenberg, was the closest the Nazis came to unlocking the secrets of nuclear energy. According to a history of the cubes by University of Maryland physicists, 664 of these nearly identical uranium cubes were arranged into the shape of a chandelier and dipped into a tank of heavy water, but still did not sustain a reaction.

As German resistance collapsed in April 1945, the scientists disassembled their lab, burying the cubes in a field, hiding the heavy water in barrels, and stashing the documentation in a latrine. Soon after, a group of American and British soldiers and scientists—including professor of physics Edwin C. Kemble, Ph.D. ’17—swept through, apprehending their German counterparts and gathering physical evidence.

Schechner is unsure how Kemble, who taught at Harvard for 38 years, managed to keep this block of uranium for himself, nor whether he saw it “as a personal souvenir” or “as evidence.” Nonetheless, she says, it “stands in silent testimony” to “a project that the Nazis long denied.”

The cube was transferred to the collection before CHSI’s formal incorporation in 1968, says executive director Joshua Gorman. Professional practice at the time enabled a long-term loan to a physics instructor who frequently used the item in the classroom. Last year, Gorman says, the cube was returned to CHSI’s safekeeping, after changes within the physics department meant it would no longer be used regularly for instruction.

Back in CHSI’s care, the object can now serve as more than “a hunk of an element,” says Schechner. It can teach about the process of scientific thinking. She noted the significance of the cubes’ standardization. Instead of just tossing uranium chunks into a pile, she says, the German scientists “were making these cubes that are roughly the same size and shape,” demonstrating “the role of measurable units in science.” The cube can also teach about Nazi science, perhaps in conversation with other experiments from that era. Fortunately, given the Nazi regime’s aims and the unlimited nature of that global war, their scientific inquiry fell short. Rather than documenting a toll of potentially millions more lives lost, the small cube of uranium now resides in Harvard’s collection, cased in lead, ready to teach about geopolitics, history, and scientific processes.