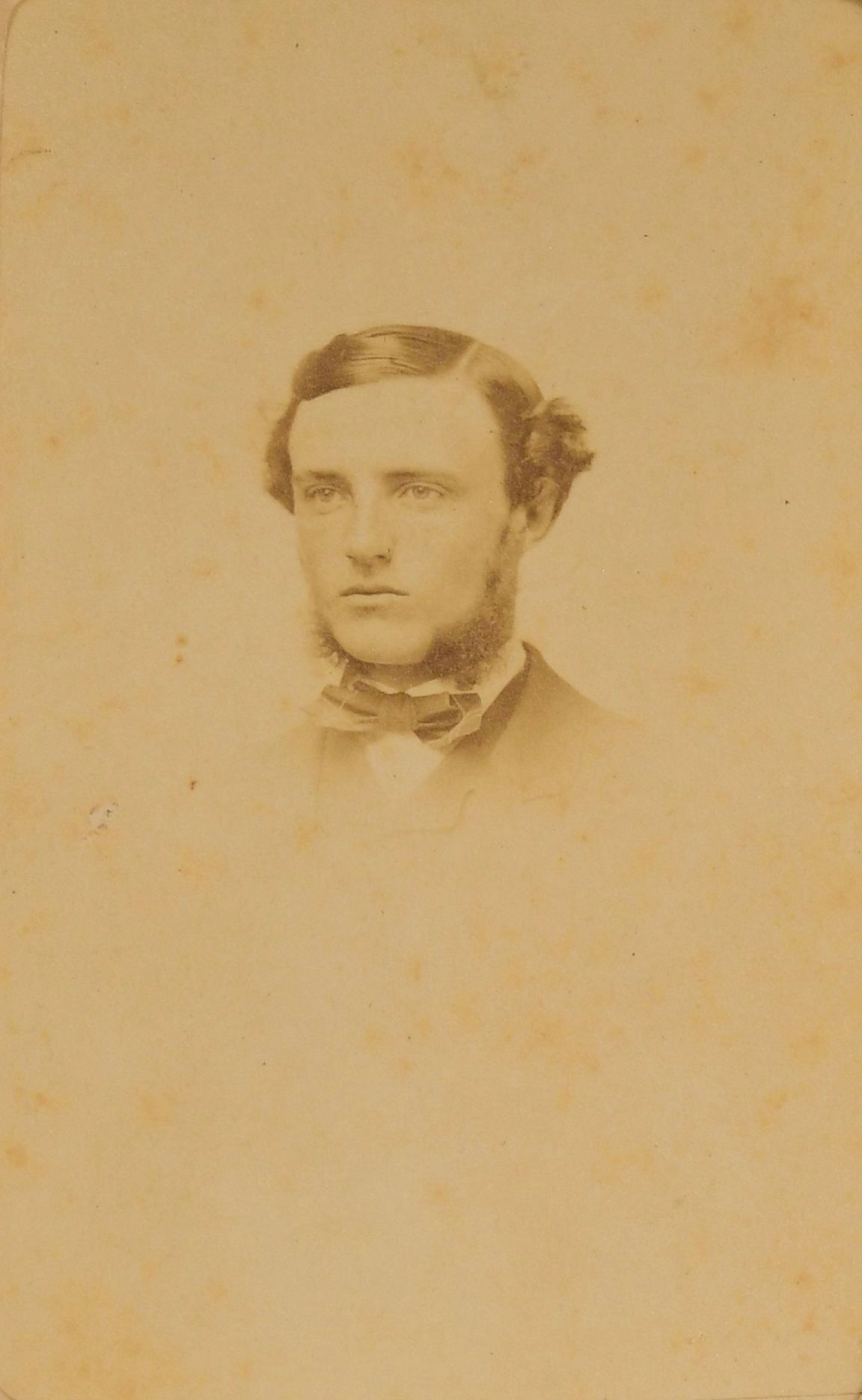

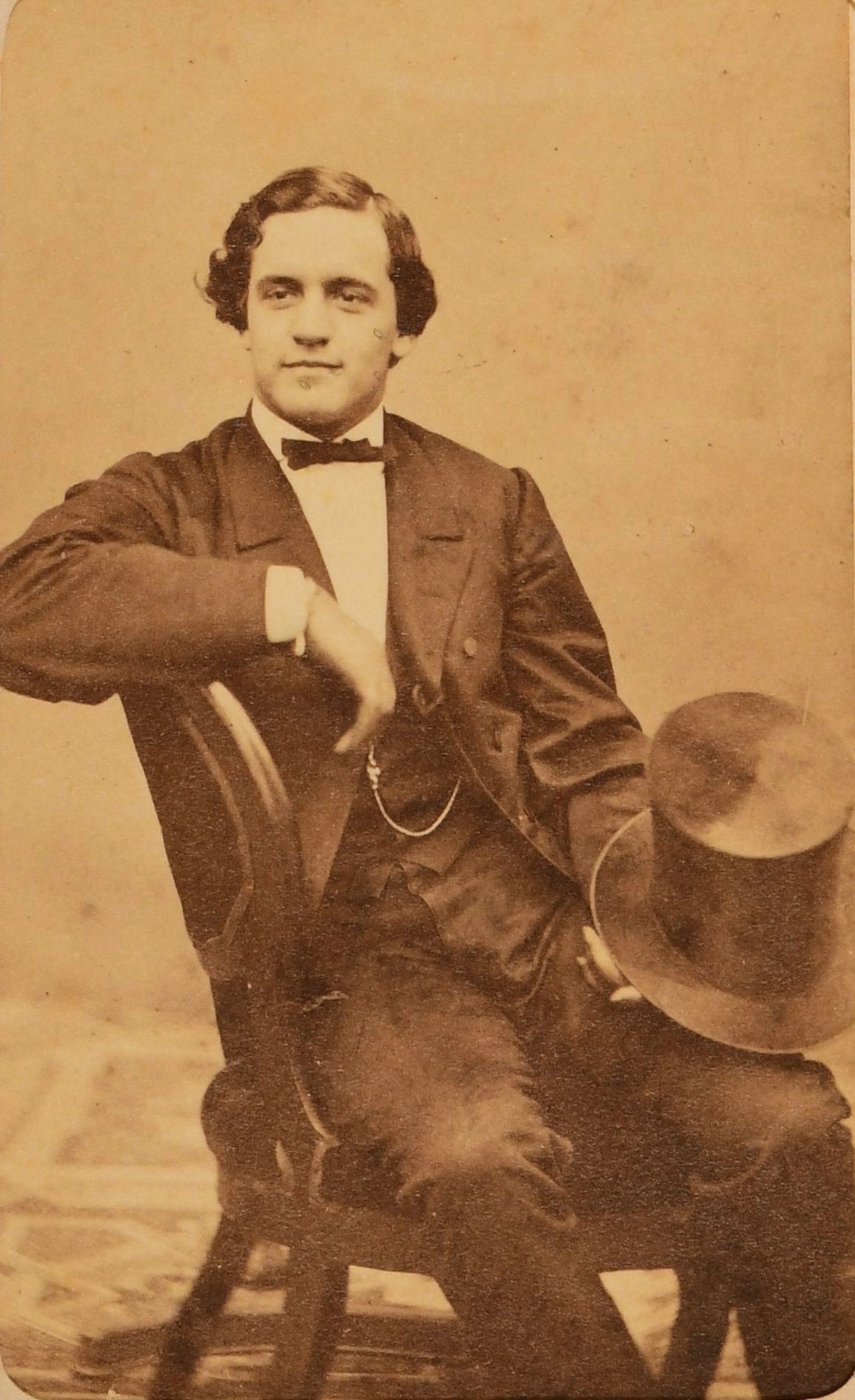

In 2004, the Rotch-Jones-Duff House and Garden Museum in New Bedford purchased a collection of documents that included the William Rotch (1844–1925) family papers. Among them were 75 letters that young Willie and his friend Henry Arnold Taber (1841–1868) exchanged between 1858 and 1861. Willie was the great-grandson of William Rotch Jr. (1759–1850), who built the house that became the museum. Both Willie and Henry would go on to graduate from Harvard. Beth Luey, a scholar and documentary historian who now volunteers at the museum, has transcribed and annotated the letters, identifying people, places, and events.

The collection may be unique in offering both sides of a correspondence between two young men at Harvard in the nineteenth century. Their studies, friendships, families, and personalities come to life in these letters. Herewith, a selection that focuses on Henry’s life at Harvard. -The Editors

“Here I am at college and thus far I like it very much indeed.”

On September 9, 1859, Henry Taber, A.B. 1863, wrote his first letter from Harvard to his childhood friend William Rotch, A.B. 1865, then a student in his last year at the New Bedford Friends’ Academy. The Academy, founded in 1810, was one of only a dozen schools outside Boston that sent its graduates to Harvard. The College also recognized it as a suitable place for students who had been rusticated for bad behavior to spend their probationary terms. Academy students welcomed these older exiles as sources of information about college life—and as valuable additions to their football team in their rivalry with New Bedford High School.

Preparing for Harvard

The New Bedford Friends’ Academy curriculum was rigorous for all students. Those hoping to attend college were given advanced instruction in mathematics and classics to prepare them specifically for the Harvard entrance examination. The eight-hour test covered Latin (Virgil, Cicero, grammar, and writing), Greek (Xenophon’s Anabasis, Homer’s Iliad, grammar, and writing), algebra, geometry, and geography. Willie told Henry that he was studying “some of the old college papers in Greek grammar and Latin prose composition.” (Harvard distributed the previous year’s exams to preparatory schools to help them shape their curriculums.) Willie continued, “We have finished and reviewed the four orations against Catiline, and are going into Virgil next term. I think it will be rather easier than Cicero has been…Greek prose composition seems pretty easy now.”

Willie was a diligent student. As the Harvard exam approached, he wrote, “I have to study so much now that I don’t have much time for anything besides taking care of my rabbits and chickens…I have to study about forty five hours in the week.”

Henry, distracted by an overactive social life, had failed the Harvard exam in 1858. His father sent him to a small boarding school in Jamaica Plain run by Rev. Joseph Henry Allen, A.B. 1840, M.Div 1843, A.M. (Hon.) 1879, S.T.D. 1891. Allen was a noted scholar, the author of a Greek grammar still in use. Despite the chaos of a household with six boarders, two monkeys, and many small children, Henry learned enough to gain admission to the class of 1863.

The boys began corresponding in 1858, when Henry was in Jamaica Plain. Willie, a scion of New Bedford’s wealthiest family, kept Henry up to date on political and social events in the town and at the Academy. New Bedford, built on wealth accumulated from whaling and shipping during colonial times, rivaled Boston in prosperity and importance. By the 1840s, its economy had shifted to finance and textile mills. It was home to a large free black population and had long been a center of abolitionist activity and a haven for freedom seekers. As the threat of civil war approached, its harbor was quickly fortified on both sides of its entrance, and Willie reported on the soldiers training at Forts Taber and Phoenix:

“Horatio Wood has been down there twice and was court-marshalled once for speaking disrespectfully to the officers. They have a pig down there, and one night Horatio got up and threw him out of the sty. He made such a squealing that sergeant Fisher got up to see what was the matter. He went into the men’s room to see who was gone, but before he got there Horatio was back in his bed and sleeping soundly.”

Until the fall of 1859, Henry had been writing about the antics of his fellow boarders, but now he was a College man. He could tell his younger friend about Harvard life—the side that probably didn’t make it into letters to his father.

Life at College

“September 9, 1859

Dear Willie,

Here I am at college and thus far I like it very much indeed. We have not been hazed at all as yet. I wish you could have been here to see the foot game or rather fight, for there is quite as much fighting as there is kicking. We beat the first two games but as most of our boys did not know the ball was by they continued kicking & the ball was sent home at last by the Sophomores. We kick now nearly every evening the real foot ball game.

I recite three times a day except Mondays and Saturdays—some Mondays four times and on Saturdays but once early in the morning. I have to study quite hard now, but I hope, when I have got used to things, and have learned to divide my time rightly, that it will not take me so long to get my lessons.

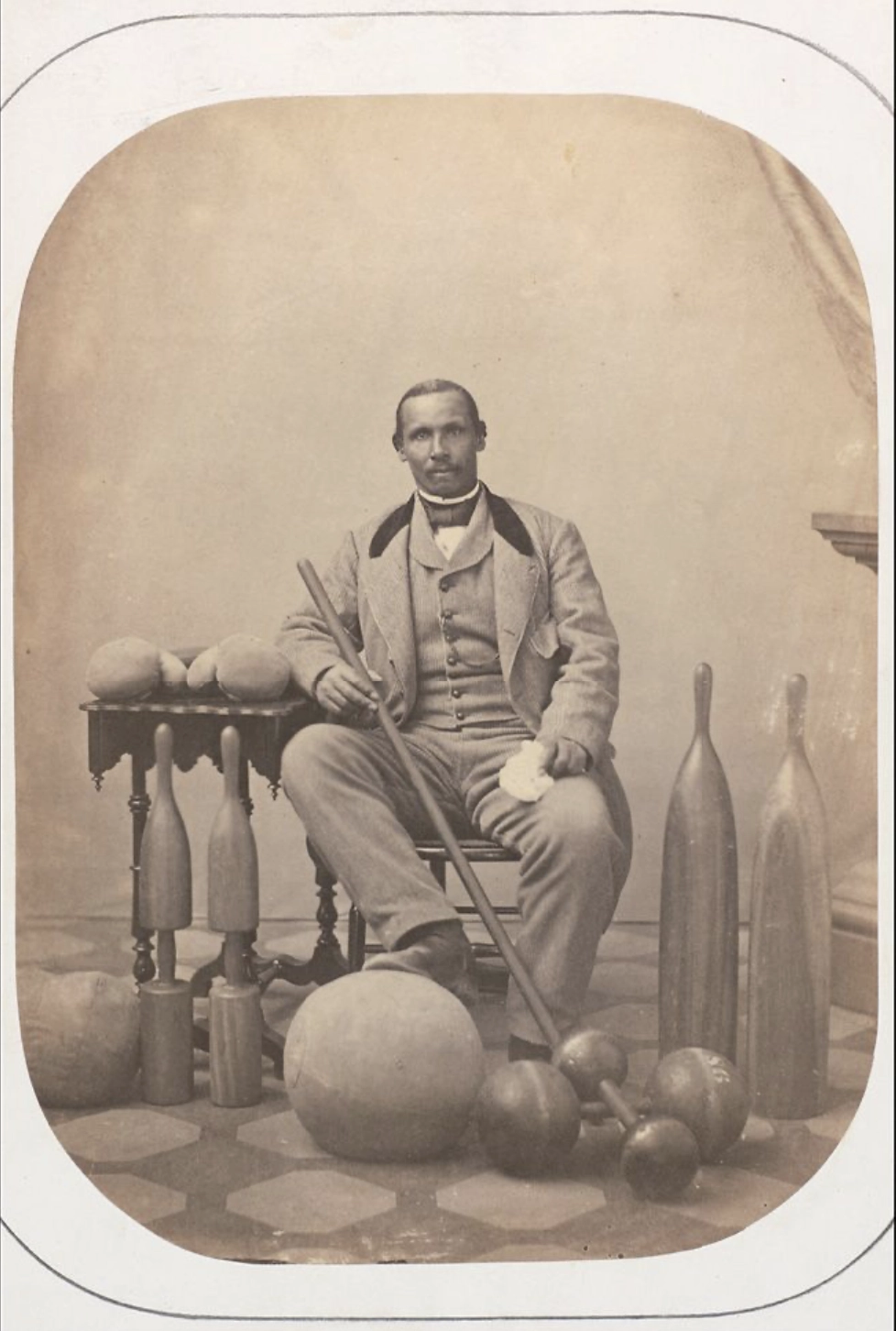

The Gymnasium which belongs to the College is to be opened next Wednesday. Each class has particular days and hours for exercise. A colored man is teacher & superintendant of it. I had heard that Mr Maggi was to be but it seems they have got some one else. You must excuse me from writing any more this time as it is time to go to bed.”

Henry spent a lot of time in the new gymnasium, supervised by Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett (1820–1871), a professional trainer and the first African American to join the teaching staff. Both boys knew Alberto Camillo Maggi (1824–1880), who taught at the New Bedford Friends’ Academy after being exiled to the United States for his role in the unsuccessful Italian Revolution of 1848.

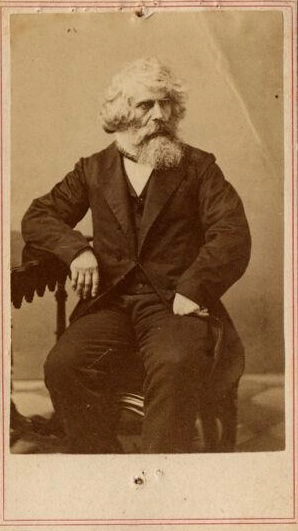

Henry wrote often about how hard he was working, but his descriptions of classes were rare. He mentioned only two instructors besides Hewlett. Evangelinus Apostolides Sophocles, professor of Greek, did not inspire him:

“Cambridge Sept 25th [1859]

…Mr. Sophocles is the funniest man. If you tell him you do not understand what he says, it makes him very angry. The other day, one fellow told him he did not understand him, but he made no reply & the fellow said so again & again. When Sophocles said, you no pay attention! Sit down! Sit down! I do not think it is right by him here, for he does not mark you as you recite well, but just as he takes a fancy to you.…Mr. Sophocles is the hardest one to get along with he will say, ‘Such and such a verb is imperfect tense is it not’ and the boy is pretty sure to say ‘yes’ and he will say ‘no tis not—de next man.’”

James Jennison, a tutor in history, did not fare much better:

“Cambridge March 25th 1860.

We study history this term & the tutor makes us draw maps of Italy. I do not see what good it does as we all trace them and he told us we might do it. Mr Genisson the tutor who heard us recite in history is a queer man. The other morning when he told us about drawing the map we kept asking him questions so that we had to recite only 20 mins out of the hour. One would ask him if he wanted the map painted—another if he wanted it drawn with ink or pencil & so on until no one could think of any more questions to ask.”

Henry wrote mostly about extracurricular activities—hazing and fighting. Early in his freshman year he wrote:

“There has been a good deal of hazing, but we have not had any yet. One fellow they made to stradle a stove pipe & bark like a dog & then they stuck his head into a pail of water. Another fellow they tossed up in a blanket, and they cut of the whiskers on one side of a fellows face, and another hair on the top of his head so that it sticks up straight. They go around and knock on the fellows doors & when they tell them to come in they open the door & squirt on them with a squirt gun.”

The faculty were not spared:

“Cambridge Nov 6th 1859.

The other night as all the Tutors were at Faculty meeting Mr. Genisson had Chinese lanterns hung out of his windows, the door to his room locked and the key hole filled with sealing-wax, and night before last they blew up the pump in the yard with powder. Saturday morning when [we] went to prayers what should we see painted on the large window over the pulpit but ’62, which means the sophomore class because it graduates in 1862.”

Along with other colleges, Harvard had long tolerated hazing as a way for students to develop class loyalty, but by 1860 the antics had gotten out of hand. The faculty outlawed hazing with some success, although, as Henry reported on September 23, 1860, “The Freshmen do get hazed some in spite of Pres. Felton but I should not want to engage in it for if you are caught you will be expelled immediately.” Nor did intramural rivalry end. Two months later, Henry boasted: “We had quite an excitement at chapel last Friday morning. Some of the Freshmen have been in the habit of coming out of our door so our fellows thought they would stop them and accordingly all halted just out side of the door standing close together so that the Freshmen could not pass between them and when the Freshmen attempted to come out our fellows gave a little push and sent them tumbling into the chapel again, but the tutors coming around soon put a stop to the fun and since then some of our fellows have been summoned to come before the faculty this evening.”

In a serious blow to college life, the College banned football, which had become a violent encounter between freshmen and sophomores. Henry reported the students’ response:

“Cambridge Sept 2 1860

Monday night we are to have a great time—a mock burial of foot ball. About seven o’clock in the evening all the class form a procession. First will come the music—a muffled drum—then the foot ball carried in a regular coffin which the six fellows who are the class crew will carry, then the class two by two. We are all to wear light colored pants with crape down the leg and a black coat and an old hat the worse looking the better. I have got one and have cut out 63 and put white paper inside to make the figures show. We are to march to the Delta, the place where we usually kick foot ball, and in one corner of the lot a grave will be dug and the foot ball buried and an oration will be delivered over the grave. We are expecting to have a great time I can tell you and I wish you could see the performance. If any of the papers have a good account of it I will send you one.”

Students did enjoy less violent social activities. On March 24th, 1861, Henry wrote:

“We had quite a nice time the other evening acting charades &c. All the fellows who room in this entry—except the Freshmen—got together in a room which no one occupies and we really had quite a nice time. I guess you would have laughed to have seen me acting the part of a woman in a charade. We had a dance too, and although we had some difficulty in telling who were gents, and who ladies inasmuch as they were both dressed alike, yet we had a jolly time of it.”

By December 1860, national events began to intrude on Harvard Yard. On the 18th, Henry wrote: “We shall lose some fellows from the South on account of the troubles about secession. The fellow who came home with me last time—Kidder from N.C. I suppose will not come back next time and there are a good many others who will not come back if the troubles continue.” In fact, Edward Hartwell Kidder (1840–1921) was the only Southern student to remain at Harvard and graduate during the Civil War (class of 1863). His brother George fought for the South.

The boys’ correspondence ended in 1861. Willie passed his entrance exams, and both boys were at Harvard that fall. However, the museum’s archives have one letter from 1863 that Willie, then a junior, wrote to his father, William J. Rotch, A.B. 1838, A.M. 1870. Letters to parents are a different genre—valuable in their way, but casting college life in a very different light:

“Cambridge, Dec. 12th, 1863

My dear Father,

I had a letter from Helen yesterday, and she says she expects to be in Boston to-morrow, and wants me to go to the Fair with her Monday evening, as it is to be opened that evening by an Organ concert. I shall go again also, for I think I can get some of my New Year’s presents there.

I got a pair of trousers the other day for $13 at Nason’s, who makes the clothes of almost all the students. The last two pair that Earle has made me have not fitted at all—they are too short at the bottom, and hardly meet the vest at the top.

My overcoat is wearing out and I shall have to get another pretty soon. I have not had a new one for five or six years, and I have worn the one that you had all the time I have been in College. The prices range all the way from $35. to $50.˜ but I think I can get a pretty good one for about $35.˜

I should like to have you send me some money for the Fair, and I shall have to pay three or four dollars for the music at the Sociables. The third one takes place next Wednesday at Miss Page’s in Watertown, and we are going to charter one or two cars to go up & come down in.

I went last evening to Mrs. Jared Sparks’, to a party given for her daughter, who is just coming out into society, and for her friend Miss Anderson—daughter of Brig. Gen. Anderson—the hero of Fort Sumpter.

I have been skating twice this week—once on Monday on Grays’ pond, and yesterday afternoon on Bird’s pond, where it was very good.

James Russell Lowell’s daughter was there and skated very well. I have not seen her at any of the parties in Cambridge, but she may be too young, although she looks as if she were sixteen or seventeen.

Prof. Agassiz lectured at City Hall last Tuesday evening on Glaciers, and this morning I went to hear him on the formation of mountains. Oliver Wendell Holmes lectures next Tuesday.

It began to snow last evening and continued till about eleven to-day, when it turned to rain, so that the skating is all gone.

I think I must have left my account book at home, for I have not seen it since I got back. I wish you would ask Morgy to look for it. I should also like to have one or two candles & tumblers.

I hope the children are all well, and Grandma & Aunt Clara.

Affectionately your son,

William Rotch”

After Harvard

Henry graduated and returned to New Bedford, where he joined his father’s firm. He died of tuberculosis on October 5, 1868, at the age of twenty-seven. He was remembered fondly by his classmates. The annual class report noted, “We can all recall his pleasant smile, his cordial greeting, and his love for his classmates. Many of us know more intimately the hospitality of his home and the virtues of his domestic life. His life was short but complete. He has left us an example worthy of our imitation, and his memory will abide forever in our hearts.”

Willie graduated in 1865 and sailed for Paris to study engineering at the Ecole Impériale Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, earning a degree in civil engineering. He became a consulting engineer for railroad companies in the United States and Mexico and was appointed a director of railroads and other companies. He remained a loyal son of Harvard, attending all the Harvard athletic events that his schedule allowed. He sent both his sons to Harvard and his daughters to Radcliffe.