The Instability of Truth: Brainwashing, Mind Control, and Hyper-Persuasion, by Rebecca Lemov, professor of the history of science (W.W. Norton, $32.99). “Brainwashing is hard to see,” Lemov writes in a timely, alarming account. “This is because it has a doubling effect, operating both on the world and on the observation of the world, so that you often cannot see it while it is happening.” An important, sweeping overview, this book encompasses everything from the formal manipulation of prisoners of war to the contemporary, technologically enabled “soft” shaping of perspectives through social media.

Learn, Lead, Serve: A Civic Life, by Thomas Ehrlich, ’56, LL.B. ’59 (Indiana University Press, $35 paper). The former Stanford Law dean, University of Pennsylvania provost, and Indiana University president also served under six U.S. presidents. His memoir (its modest title seems almost shocking today) will resonate with alumni of a certain age, evoking the “Red Book” curriculum and such faculty titans as Louis Hartz, I. Bernard Cohen, V.O. Key, and Samuel Huntington. Other insights echo more broadly: recalling his undergraduate studies, Ehrlich writes, “there was not a single teacher who was a woman,” nor “a single Black or Latino faculty member”—a circumstance fortunately now changed. But there have also been changes for the worse: reviewing his College coursework, he is “struck by the extensive comments my teachers wrote in the margins and at the end of the papers.”

Dreaming in Ensemble: How Black Artists Transformed American Opera, by Lucy Caplan ’12 (Harvard, $35). Of what practical use is a Harvard College concentration in history and literature? When combined with a Yale master’s concentration in public humanities and a doctorate in American and African American studies, plenty, equipping the author to become assistant professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. There, she blends historical scholarship on music, race, and culture, as in this deep dive into a counterculture of a century and more ago: composer-critic Nora Douglas Holt, soprano Caterina Jarboro, composer Shirley Graham Du Bois (whose Tom-Tom, premiered in 1932, was reviewed and discussed nationwide), and others. A revelation.

By the Second Spring: Seven Lives and One Year of the War in Ukraine, by Danielle Leavitt, Ph.D. ’23 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30). A postdoctoral fellow at Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute looks beyond the body counts and geopolitics—which have become especially harsh of late—to capture the experiences of “most Ukrainians [who] remain unknown and faceless, represented only abstractly in blue and yellow flags hanging from the occasional window.” Leavitt’s accounts push back against the “flattening” of fellow human beings, rendering them “palpable and resonant” as they “live inside the madness of an unwanted and brutal modern war.”

Clamor, by Chris Berdik ’96 (W.W. Norton, $29.99). The moron babbling into his cell phone on the bus and the jet roaring overhead are both part of “how noise took over the world” (the first part of Berdik’s subtitle for Clamor), leading to hope about “how we can take it back” (the merciful coda). The conundrum is that “sounds can trigger a visceral, even furious response from us in the moment, but barely a shrug when that moment passes.” Time to hold that response in mind, and raise a hue and cry about ubiquitous noise assaults.

Funny Because It’s True, by Christine Wenc, A.M. ’08 (Running Press, $30). Writing from her native Wisconsin, where she was present at/participated in the creation, Wenc details “how The Onion created modern American news satire” (the subtitle). It’s a real history, beginning appropriately with the folkloric concept of “the trickster.” That The Onion surely is. The publication often misses, and can be juvenile, but its capacity for equal-opportunity offense remains important—especially given the absurdist material daily at hand in political discourse, marketing blather, and pervasive dunderheadedness.

The Meddlers: Sovereignty, Empire, and the Birth of Global Economic Governance, by Jamie Martin, assistant professor of history and of social studies (Harvard, $24.95 paper). Economic institutions like the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, and the World Bank often become controversial when they work their will on sovereign nations that, say, incur too much debt or impose regulations that global regulators oppose. Martin traces these tensions to the origins of the League of Nations and the Bank for International Settlements, created after World War I. Struggles over attempts to legitimate such exercises of power as acts of international cooperation, rather than as coercive, date to their beginnings. The history matters now, when the U.S. government is challenging such arrangements. So does Martin’s observation about “how difficult it has always been to achieve real international cooperation, but also how dangerous giving up on it can be.” (See harvardmag.com/international-finance-23 for more about Martin’s scholarship.)

The University Unfettered: Public Higher Education in an Age of Disruption, by Ian F. McNeely ’92, JF ’98 (Columbia, $30 paper). A professor of history who is senior associate dean for undergraduate education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill examines what befell public universities from the Great Recession through the pandemic, as their state funding was decimated even as they sought to meet new demands. Although he is “profoundly ambivalent” about what such institutions have become—in emulation of the endowed private universities—he remains optimistic: “I…find it deeply uncomfortable to endorse such a thoroughly market-driven vision of the university’s role…, the exclusions it entails, and the meanness of spirit and waste of resources that relentless competition can invite. Yet I am forced to concede that productive rivalry is one of the few constants in the history of higher learning….” One may wonder, and worry, how that plays out in the environment for higher ed since his manuscript went to press.

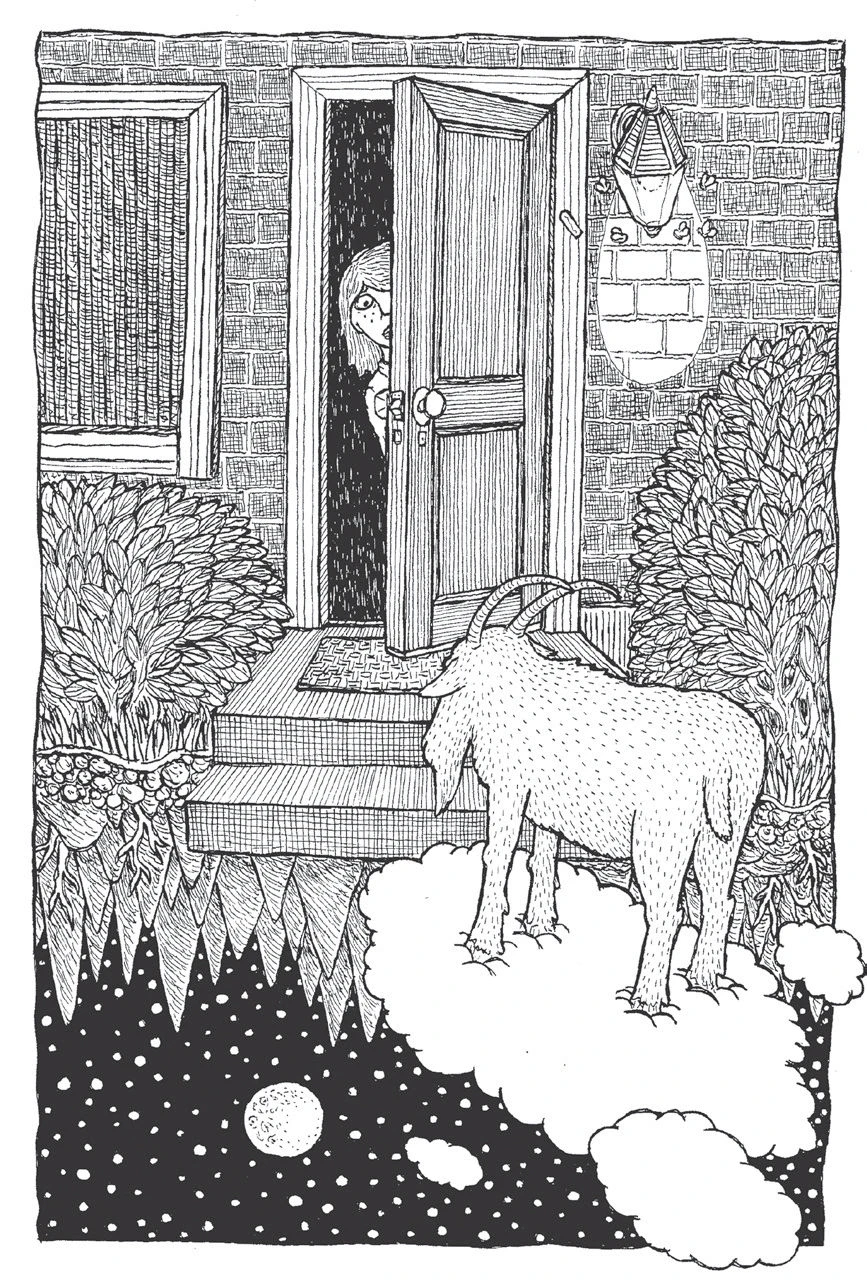

One Little Goat: A Passover Catastrophe, by Dara Horn ’99, Ph.D. ’06, illustrated by Theo Ellsworth (Norton Young Readers, $18.99). A middle-grade graphic novel on a Passover theme, somewhat alarmingly illustrated in black-and-white line art, written by Horn, the novelist and author of People Love Dead Jews; the author was profiled in these pages in “A Novel Take on Eternal Life” (January-February 2018, page 55).

Ellmann’s Joyce: The Biography of a Masterpiece and Its Maker, by Zachary Leader, Ph.D. ’77 (Harvard, $35). This may be a bit meta, but there is a substantial rationale for a biography of the biographer whose James Joyce (1959) is considered the twentieth-century exemplar in its field. Leader (general editor of The Oxford History of Life-Writing and the biographer of Kingsley Amis and Saul Bellow) handles his material to great effect: the “very different family [Richard] Ellmann was born into,” compared to his subject’s, immediately comes into play, as “its influence on his life and writing is clear, a source of his own sympathy and humanity—perhaps, also, of his depictions of Joyce as family man and of Joyce’s Bloom as family man.”

Ping: The Secrets of Successful Virtual Communication, by Andrew Brodsky, Ph.D. ’17 (Simon Acumen, $28.99). The author, possessor of a Harvard Business School organizational behavior doctorate, is assistant professor of management at the University of Texas at Austin McCombs School and CEO of Ping Group (really). A cancer survivor with associated immune deficiencies, he has a unique perspective on the value of interacting with others at a remove. “We’re all acutely aware of what it looks like when virtual communication goes wrong,” he acknowledges, but his focus is “the flip side…when things go right.” Hence this guide to navigating all the options “from mode choice to message framing.”