Look through the hole, and a world appears in miniature: a train chugging down a tree-lined track, pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages bustling on either side. This optical illusion is a “paper peepshow”—a device that layered paper cutouts to create a three-dimensional scene. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these tiny theaters captivated crowds in salons, village squares, and fairs across Europe. Relatively few of the fragile creations survive, but two are housed at Harvard Business School’s Baker Library.

The peepshow’s rise mirrored the rapid expansion of Europe’s material world. In the eighteenth century, travelers mapped distant lands, royalty staged lavish operas, and astronomers explored the cosmos. Yet for most Europeans, these discoveries remained distant, only accessed secondhand—until the peepshow arrived, offering a pocket-sized portal to far-off worlds.

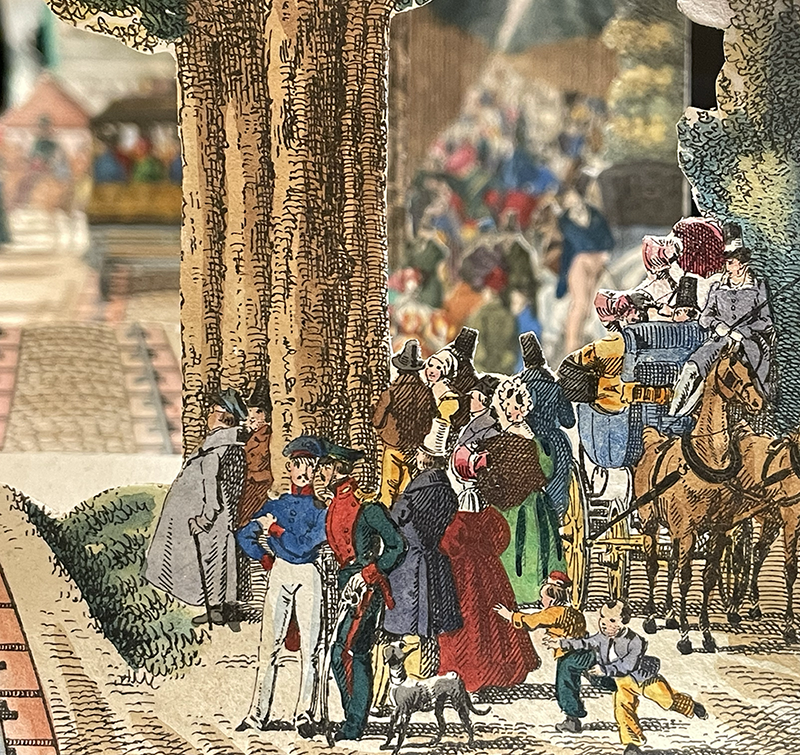

Augsburg engraver Martin Engelbrecht was a pioneer of the artform. He designed sets of six engraved cards—one solid backdrop and five cutouts—each of which was slotted into a boîte d’optique, a box with slots for each card and a peephole at the front. His first peepshows replicated the grand scenery of contemporary operas, offering ordinary viewers a glimpse of the unobstructed stage (a privilege usually reserved for those in the imperial box). He then began to depict more quotidian moments, turning mundane scenes into spectacles. One such work, held at Harvard, transports viewers to a fair in Engelbrecht’s home region. The layered cards bring to life a lively marketplace: merchants hawking textiles and tableware, figures weaving through the crowd, three performers on a stage. The final layer reveals a distant skyline, adding depth and heightening the illusion.

Starting in the 1820s, a simple innovation made the boîte d’optique obsolete: bellows on the sides of the cards. Now, viewers could hold the front card to their eyes and allow gravity to pull the others into place. The Baker Library holds one such example from around 1835, depicting Germany’s first railroad, the Nuremberg-Fürth Railway. Unlike Engelbrecht’s carefully engraved sets, these peepshows were mass-produced—offering viewers a glimpse of a technological wonder that few could witness firsthand. Then as now, the peepshow offered an intensely personal escape, sealing off the present and drawing the viewer into another place or time.