In a drawer in Harvard’s Museum of Natural History lies a skeleton of Lachnolaimus maximus, the hogfish, its delicate bones wrapped in a yellowed, crinkled letter whose paper lay untouched for more than 100 years. “My dear father,” the letter begins in Spanish, “The other day I sent you…fifteen and a half yards of cloth for wrapping fish. The barrel left on Saturday, and you should have received it by now….” It is signed “Your daughter, Amelia.”

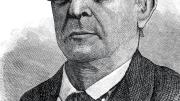

Felipe Poey, the fish aficionado so impatient to send this fish to Harvard that he wrapped it in a letter from his own daughter, was one of the most prolific but sadly underappreciated naturalists of the nineteenth century. Born in Havana to a French father and Cuban mother, he moved with his family to France when he was five, and in three formative years there developed a lifelong appreciation for the natural world and for the arts. His subsequent education in Cuba, and briefly in Spain, trained him for the law, but his return to his native country reawakened his passion for natural science and collecting (fish, in particular). When he moved to Paris in 1825 with his Cuban bride to resume his law practice, he brought along a series of his own drawings of Cuban fish and a barrel containing more than 80 fish preserved in brandy. He quickly integrated himself into the network of leading European naturalists by sending his drawings and samples to the premier ichthyologist of the time, Georges Cuvier, now considered the father of comparative anatomy and paleontology. Cuvier was so impressed that he included several new species credited to Poey in his Natural History of the Fishes and invited the young man to become his student.

Poey returned to Cuba in 1833 and dedicated himself to studying and cataloguing its wildlife, publishing in several languages and winning many awards. In 1839 he established Havana’s Museum of Natural History; in 1842, he became the first professor of zoology and comparative anatomy at the University of Havana. As an official correspondent of the New York Lyceum of Natural History, the Boston Society of Natural History, and other prestigious institutions, he was in touch with many prominent scientists, including Louis Agassiz, the founder and first director of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. The two men maintained a lengthy correspondence, and Poey supplied hundreds of samples to Agassiz’s museum, most of which remain wrapped in letters or, more often, Cuban newspapers. (Indeed, he was preserving more than fish; he was saving pieces of history, both Cuba’s and his own. The digital archives of the newspapers in which he wrapped his samples go back only to 1890, making the fragile copies currently cradling iridescent fish skeletons at Harvard some of the few, if not the only, issues available in North America.)

When he prepared the hogfish for Agassiz in 1869, Poey was 70, still busily collecting specimens, teaching, and writing his magnum opus: Ictiología Cubana, a compendium of all the fish in Cuban waters—a labor of love that he kept expanding until his death. In the note that accompanied his 1883 manuscript of 758 species, Poey wrote, “The preparation of the text has cost me an immense amount of time and labor. In the determination of the species it is rarely that a single one has not occupied me for an entire week. I have wished to make known the certain as certain, and the doubtful as doubtful, so that I shall declare nothing to be new unless it is so in reality.” (The complete, two-volume work remained unpublished until 2000, just after the bicentennial of his birth.)

Poey regarded naturalism as not only his profession but his calling, and valued it for reasons that transcended scientific discovery:

While one part of humanity, diverted from its higher destiny, wages war against the other, the naturalist takes refuge in Nature’s breast, and asks the Supreme Being for peace and happiness for all. He does not aspire for riches nor power; he sees a brother in every man. He cultivates his own understanding, because it must be his faithful companion when grace, agility, love and health abandon his body in old age. He prefers to study natural history...because it enlarges his soul, initiating it into the sublime mysteries of Creation, which exalt in his unblemished, moral intelligence.

Why is he so little known today? In part, because students at the University of Havana preferred to study the “new” fields of medicine and engineering. With little local support, Poey built an international ecosystem of colleagues who disseminated his work, allowing him to focus on what he knew best: the fish of Cuba. He visited the Havana fish markets daily to see what potential new species he could find: in an 1884 profile of Poey for Popular Science Monthly, ichthyologist David S. Jordan reported that a visiting naturalist need only claim to be a “friend of Don Felipe’s” to elicit honorable treatment and sincere offers of assistance from the local fishermen, who had become his friends.

His specimens still lie largely untouched at Harvard, but for Poey, their preservation alone would probably be recognition enough. He was “simple, direct, unaffected, but possessed of a quiet dignity…certainly one of the most delightful men I have ever met,” wrote Jordan at the end of his sketch. “Of all men I have known, he has best learned the art of growing old.”