In 1895, Harvard deployed the most powerful photographic telescope in the world to a high-altitude observatory in Arequipa, Peru, where it played a seminal role in discoveries about Earth’s placement in the cosmos, and ultimately, the expansion rate of the universe.

The Bruce telescope owes its name, fame, and subsequent rediscovery, respectively, to three women. Miss Catherine Bruce, a wealthy, unmarried New Yorker, donated $50,000 to have the telescope built, and thus gave the instrument its name. (The lens blanks, ordered from a French glass manufactory, took three years to arrive). It owes its place in history to Henrietta Leavitt, an 1892 Radcliffe graduate employed at the Harvard College Observatory, who in 1908 published her observation that the peak brightness of certain pulsing stars called Cepheids was related to the length of their pulsing cycle, or period. Later astronomers realized that this fundamental insight could be used to calculate the distances to these unusual stars, by comparing a Cepheid’s observed brightness from Earth to what its brightness should be based on its period. Edwin Hubble used Cepheids in the 1920s to establish that the Milky Way was just a single galaxy in a universe of many, while John Huchra, the late Doyle professor of cosmology, used them in 1993 to help calculate the Hubble constant, the expansion rate of the universe.

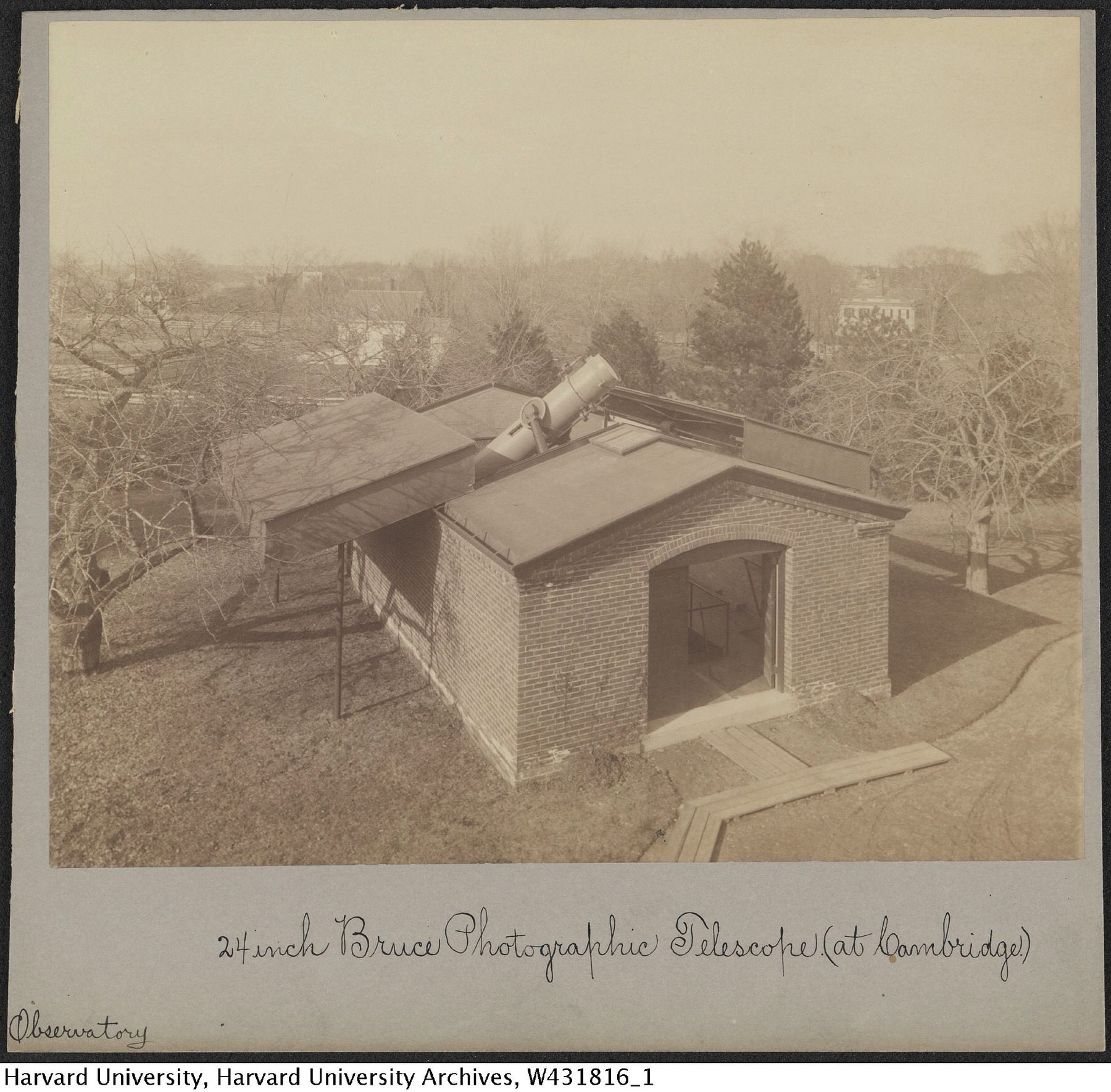

The Bruce Telescope as set up in Cambridge, ca. 1893-1895

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

The Bruce Telescope as set up in Cambridge, ca. 1893-1895

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

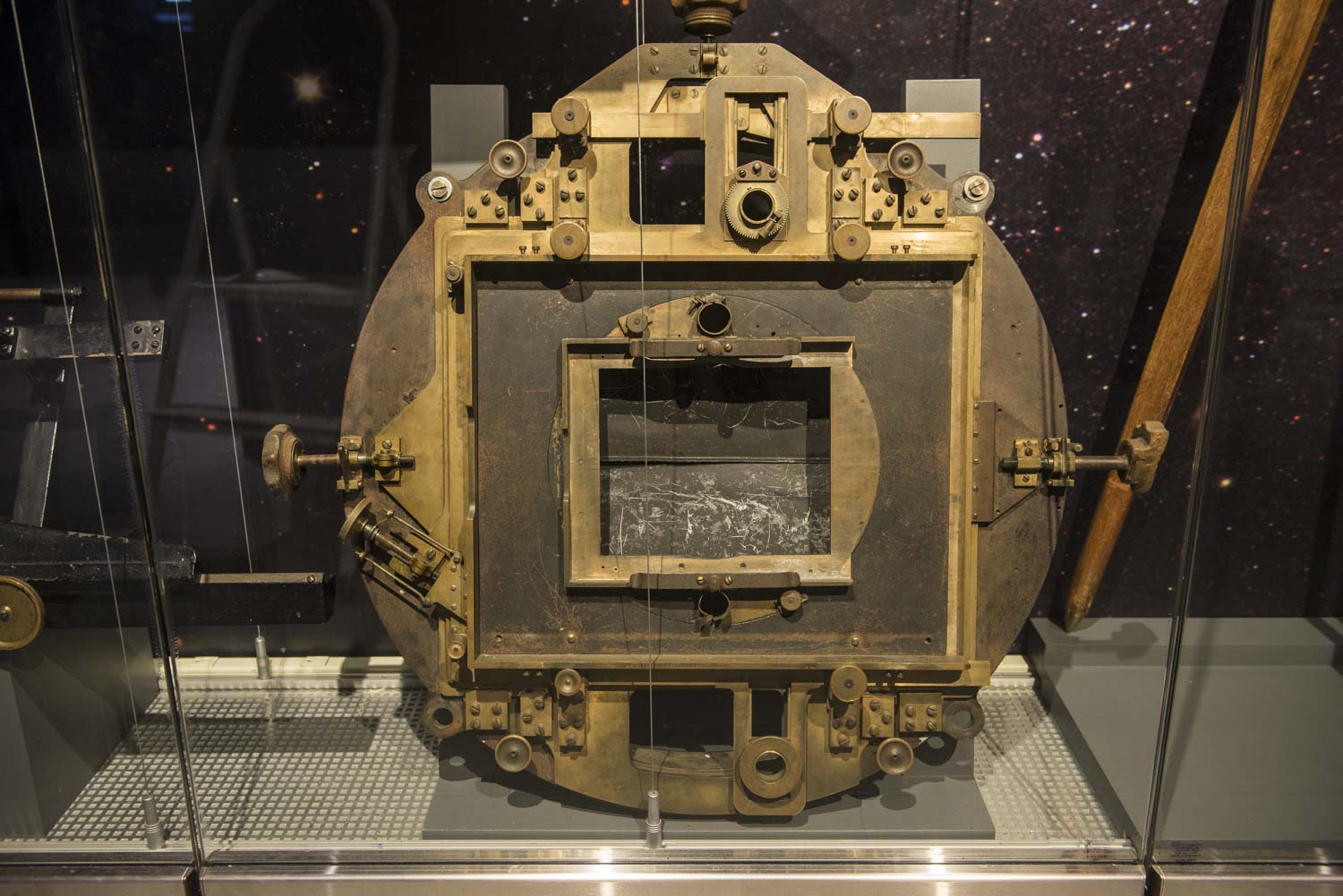

This double-side plate holder served as a tailpiece of the Bruce photographic telescope. It held glass plates as large as 14 inches by 17 inches.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Arequipa Station (Peru), view from west, El Misti in background, with the 24" Bruce telescope dome completed, ca. 1897-1915

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard College Observatory Library

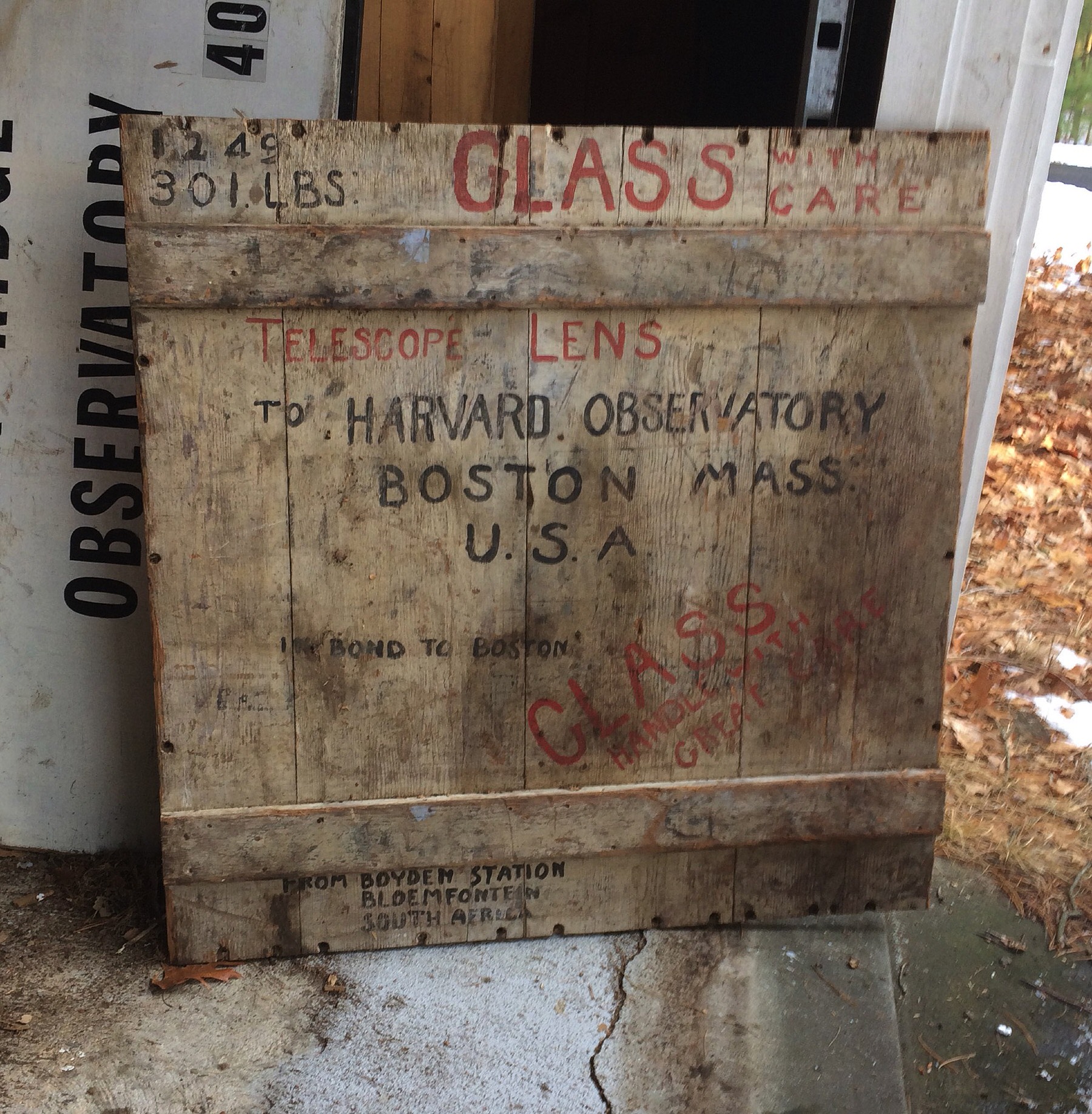

Part of a shipping crate used to return the telescope from South Africa to Cambridge

Photograph courtesy of Sara Schechner

A portion of the disassembled telescope

Photograph courtesy of Sara Schechner

But the telescope itself, if not its contributions to scientific discovery, might have been lost if not for Sara Schechner, Wheatland curator of the Harvard Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, who recently stumbled upon its lenses while doing reconnaissance at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics’s decommissioned Oak Ridge site in Harvard, Massachusetts. (The scene, she says, with trees growing up around abandoned buildings and garages, was right out of Planet of the Apes.) The telescope had been shipped from Peru to South Africa in 1927, but its fate after the 1950s was undocumented until Schechner found the lenses, wrapped in flannel and padded with pillows of hair and straw (inhabited by mice), still in the wooden crates shipped back from South Africa. Once she realized what they were, she located the rest of the telescope in a building nearby. Now restored, the lenses and their original brass and cast-iron holders (called “cells”) are on display, destined for the permanent collection she oversees, where the contributions of Catherine Bruce and Henrietta Leavitt will long be remembered.