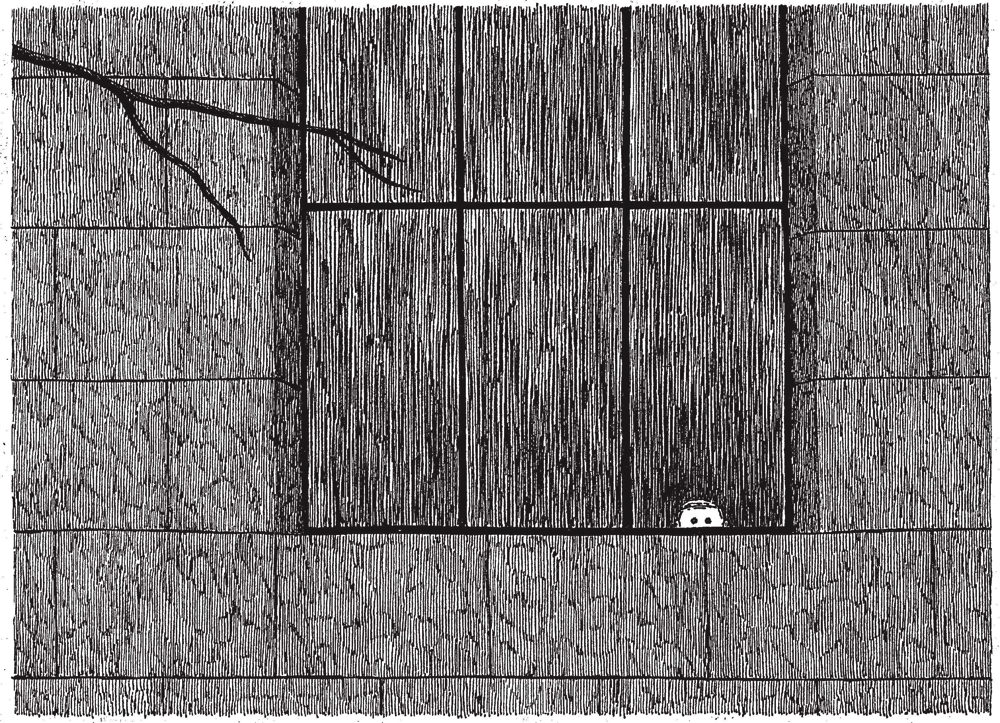

A very small boy, only his eyes and forehead visible, stares out of an enormous, tall window three panes across. The tip of a single bare tree branch, which he does not see, stretches down toward him from the top left. It may be raining, though the fine vertical cross-hatching makes it hard to tell. Below, a caption, in the style of an old-fashioned primer: “N is for NEVILLE who died of ennui.”

This was a favorite drawing of its creator, Edward Gorey ’50, from The Gashlycrumb Tinies, a mock-schoolbook that teaches each letter of the alphabet with an illustration of a child’s death, usually violent. “N” captures a number of Gorey’s characteristic preoccupations: humor simultaneously absurd and deadpan, the subversion of a children’s genre, the vaguely English sound of the name “Neville.” The drawing (black and white, in pen) is spare to the brink of geometric abstraction, yet also lavish in its meticulous hand-drawn imitation of the fine lines of nineteenth-century lithography. The caption is terse, yet also hyperbolic. The joke turns on the last word: “ennui,” redolent of France and fainting couches, is far funnier than “boredom.”

The unfortunate Neville, “who died of ennui” in Gorey’s alphabetic mock-schoolbook

Used by permission of the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust

During the course of a five-decade career as an illustrator, designer, and author, Gorey became famous for his category-defying small books—bearing titles like The Doubtful Guest, The Beastly Baby, The Curious Sofa—filled with dark, cartoonish surrealism and Anglophilic light camp. He began publishing almost as soon as he graduated from Harvard, and his popularity surged when his work was anthologized in the 1970s. Gorey’s talents, however, ranged well beyond those books. As a young commercial artist, he produced a number of striking book covers and illustrations; later, success opened opportunities to design costumes and sets for ballet and theater, including Dracula, for which he won a Tony. After he left New York City for Cape Cod in 1985, he passed much of his time creating small, barely comprehensible plays for local performance and his own amusement.

Describing only Gorey’s work, however, leaves out the many memorable eccentricities of his personality. He was a legendary balletomane who attended nearly every performance of the New York City Ballet during the Balanchine era from 1956 to the choreographer’s death in 1983. Tall and thin (a bit like the figures in his drawings), he accentuated his height with a collection of rippling fur coats, many in unusual colors—a get-up he adopted at Harvard and continued to wear into his sixties. His many rings and earrings, together with his thick beard, gave him a somewhat wizardly appearance—comically tweaked by wearing only old canvas sneakers below. He loved obscure old films, and thought the advent of talkies killed cinema. His homes came to resemble library-museums, bursting with books and unnerving relics: various mummy parts, battered stuffed animals, Roman coins, and an extremely large collection of rusting metal objects.

Mark Dery’s new Gorey biography, Born to Be Posthumous, applies inquisitorial fervor to its subject alongside a fan’s mania; at times, it is hard to tell whether Dery is worshipping Gorey or prosecuting him. “How to get to the bottom of a man whose mind was intricate as Chinese boxes?” he asks at the beginning of a book filled with half-answered rhetorical questions.

It’s clear what Dery thinks is in that smallest Chinese box: Gorey’s sexuality, to which he returns obsessively, at a level of scrutiny that Joseph McCarthy and J. Edgar Hoover couldn’t have bested, measuring each and every episode in Gorey’s life (and most of his art) against the question of whether he was gay. Gorey himself said he had occasional crushes and nothing more, remarking, “I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something. I’ve never said that I was gay and I’ve never said that I wasn’t.”

Dery is unwilling to let his subject’s stated indifference to romantic relationships stand, insisting that there must be some underlying truth of the matter. (For a biographer who repeatedly invokes various deconstructionists, he has a strange monomania for placing Gorey firmly in established categories of sexuality.) It is helpful to point out queer themes in some of the creative work—the title character in The Doubtful Guest, for example, may be read as a way of talking about queerness and social exclusion—but in Dery’s hands, these aspects start to overwhelm almost every other facet of his subject’s life, forming a feedback loop where the work attests to sexuality and sexuality deciphers the work. Dery thinks “media coverage of Gorey is consistently—and a little too insistently—oblivious to the gay themes in his art,” but he himself swings to the other extreme, making central a biographical issue Gorey repeatedly insisted was less important to him than others wanted to make it.

The book’s other main project is to vindicate Gorey as a genius by any means possible, usually by insisting that he either built on the work of brilliant predecessors or anticipated the work of brilliant successors—a wild gang including the I Ching, Samuel Beckett, Jacques Derrida, Roland Barthes, Peter Singer, René Magritte, Jorge Luis Borges, the Oulipo group, The Tale of Genji, Oscar Wilde, Art Spiegelman, Jean-Paul Sartre, and The Simpsons. (Dery reminds us multiple times that Gorey had an IQ of 157.)

The biography could easily have been titled Edward Gorey: Gay Genius. Dery thinks that people don’t take Gorey’s art as seriously as they should, writing in his introduction, “Only now are art critics, scholars of children’s literature, historians of book-cover design and commercial illustration, and chroniclers of the gay experience in postwar America waking up to the fact that Gorey is a critically neglected genius.” He undermines this assessment 400 pages later in enumerating the reactions to Gorey’s death in 2000: obituaries in every major newspaper in America and Britain (two in The New York Times), Le Monde, People magazine, a tribute featuring Gorey’s work in The New Yorker.

The enthusiastic audience in the artist’s own time included Edmund Wilson and Robert Gottlieb, who understood Gorey was doing something more than mere cartooning. As early as 20 years ago, he was the subject of such academic citations as George Bodmer’s “The Post-Modern Alphabet: Extending the Limits of the Contemporary Alphabet Book, from Seuss to Gorey” (Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 14/3, Fall 1989). Since his death, he has been the subject of multiple museum exhibitions. Dery seems to want to paint a picture of an artist transforming slowly in death from a kiddie cult object to an acknowledged great—but by his own account, the serious appreciators were there from the late 1950s onward.

The biography’s greatest strength is its use of interviews—many new, conducted by the author—and correspondence. Dery spoke with a number of Gorey friends and colleagues (who might never have been put on the record at such great length otherwise) about his life, and their recollections help soften a man who can come across in old profiles and interviews as calculatedly flippant about his own life and feelings.

Even in youth, Gorey moved in circles of remarkably accomplished people. He was a high-school classmate of the painter Joan Mitchell, and roomed in Eliot House with the poet Frank O’Hara ’50, with whom he had a close, if complicated, friendship. (Dery credits Gorey with helping O’Hara accept his homosexuality; the two apparently fell out shortly after graduation over a belittling remark by O’Hara about Gorey’s drawings of “funny little men.”) The recollections of novelist Alison Lurie ’47, a close friend of Gorey’s in their years just after college, together with Gorey’s early letters to her after graduation, provide an especially vivid portrait of a young artist of abundant raw talent trying to find his métier. Born to Be Posthumous is at its best when it shows Gorey through the eyes of others, especially because those others often have their own rich gifts of perception: the poet John Ashbery ’49, Litt.D. ’01, the publishers Jason and Barbara Epstein ’49, the artist and writer Maurice Sendak.

It’s helpful to read these contemporaries’ impressions because they provide some of the context necessary to make sense of Dery’s portrait of Gorey as a man out of temper with his own time, for whom an infatuation with a hazy Anglo-French fin-de-siècle was as much a reaction against the cheery conformism of the 1950s as Beat poetry or rock and roll were. This landscape was almost entirely fantasy: though Gorey was steeped in English and French art and literature, he never actually visited either country, and seems to have resisted doing so lest modern reality shatter his illusions. In an effort to highlight Gorey’s innovativeness, Dery wants to make this a kind of avant-garde impulse re-directed onto the past (“avant-retro,” he calls it, slipping into interlingual oxymoron). But there is a different word for an infatuation with times before your own—antiquarianism—which seems to apply to Gorey (owner of mummy parts, Roman coins, Victoriana) pretty well. Despite Dery’s repeated efforts to make him a person “ahead of his time,” the reader comes away with a sense that Gorey would have taken “innovator” as a slur.

Dery’s voice can exasperate at times. The biography has odd tics that start to grate after the first 50 pages or so. Time after time, it cajoles the reader down avenues of speculation (“It’s hard not to see,” “One can’t help wondering”), even when the conclusion drawn is not at all self-evident. Its author has a habit of needlessly invoking impressive-sounding cultural references, as if to dignify Gorey by association: his putative asexuality is called “very Taoist of him” and illustrated with an allusion to Melville’s Bartleby; The Unstrung Harp evinces “disenchantment with language reminiscent of Beckett or Derrida.” A little of this is fine (Gorey did love Beckett, and called him an influence), but here it is ubiquitous and becomes unilluminating.

At worst, the implausibility of the connections drawn sometimes undercuts appreciation of Gorey’s work. Twice Dery unconvincingly refers to Gorey and O’Hara as “postmodernists avant la lettre” solely because Gorey asserted “the virtues of anachronism.” It’s not clear what is meant: “postmodernism” usually means some kind of stylistic blending or questioning of master narratives, neither of which quite seems to fit Gorey and O’Hara. Moreover, the label draws attention away from what Gorey was actually doing with faux-Victorianism and antiquarianism.

“If his life looked, from the outside, like an exercise in well-rutted routines, its inner truth recalls the universe as characterized by the biologist J.B.S. Haldane: not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose,” Dery writes in his introduction. That sentence, in style and substance, sums up much of this biography’s approach. Gorey was full of idiosyncrasies, but the book sets those peculiarities at the heart of everything, leaving little else to talk about: every aspect of Gorey’s life assumes the scale of an eccentricity, even his very normal TV habits in old age. (He enjoyed The Avengers and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.) By the end, it’s hard not to return to Dery’s image of the Chinese boxes: the smallest one is usually empty. The boxes themselves, however, are the real work of art, and a full biography of Gorey, a man who devoted as much aesthetic detail to his lifestyle as to his work, is welcome.