Amid the triumphant fanfare of the Harvard Tercentenary celebrations, Radcliffe College’s 1936 exhibit on “Women in Science” was remarkably unassuming.

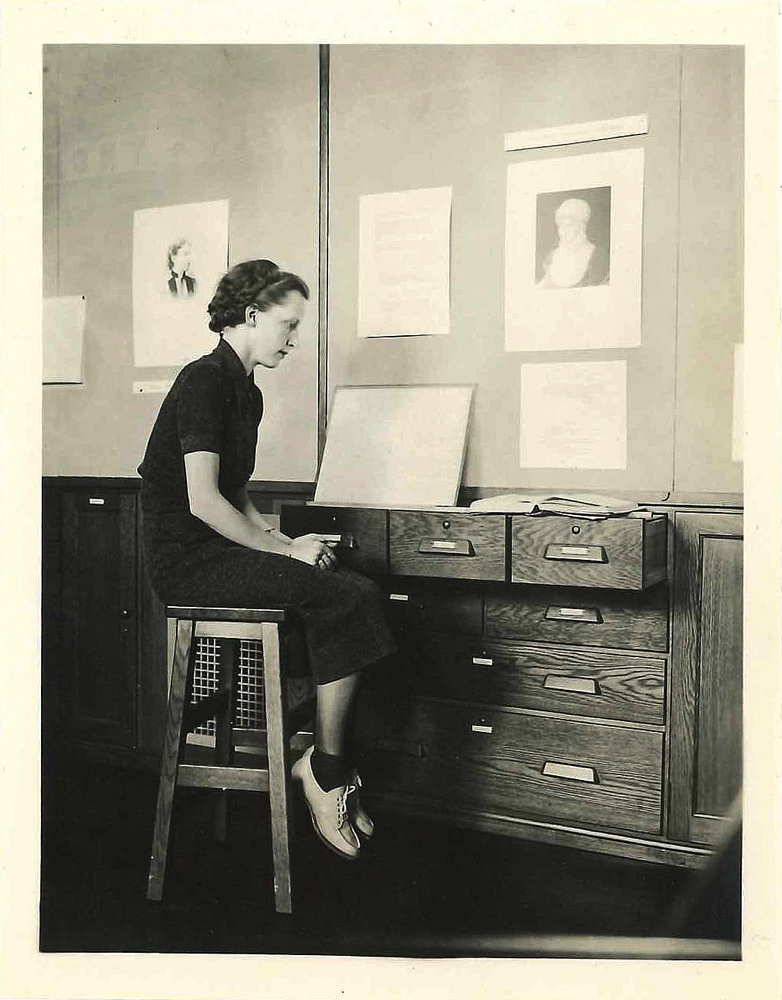

The exhibit marked the first Harvard centenary to celebrate women in university life. Tucked into a second-floor room of Byerly Hall, Radcliffe’s newly inaugurated science building, it showcased the work of nearly 200 “outstanding” women in the fields of astronomy, biology, chemistry, physics, and medicine.

Most displays featured women who were not household names like Marie Curie. They were scientists whose research was less earth-shattering, representing “good work which has been done […] by women who do not claim to be genius.”

The number of women in science had risen dramatically during the early decades of the twentieth century. But by the mid 1930s—at the low point of the post-Depression labor movement, and in a political climate that was increasingly unsympathetic to direct claims of inequality—women scientists at Radcliffe and beyond wanted to protect their hard-won professional gains. Many were reluctant to employ the radical feminist rhetoric of prior decades to agitate further for equality. Instead, they favored a nonconfrontational strategy of hard work and stoicism.

Photograph of the exhibit courtesy of Schlesinger Library/Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study

The exhibit echoed this conservative ethos, embracing the advice of exhibit committee member Elisabeth Deichmann, Ph.D. ’27, to avoid the “old militant spirit.” One contributing scientist noted that the exhibit was so “moderate” in tone that it even verged on “dullness.”

Similar restraint characterized the exhibit’s physical design. A “Letter to the Visitor” admitted that there was “very little material that is graphic or interpretive” on display. Instead, each scientist was represented by a folder containing reprints of her published articles.

These reprints may have been visually unremarkable, but they could be cheaply acquired, easily mailed, and uniformly mounted, making them ideal items to collect and arrange systematically. More importantly, a published article represented its author’s expertise and authority within the scientific community.

Like the exhibit’s moderate rhetoric, its assemblage of reprints showed en masse the accomplishments of women scientists through incontrovertibly unostentatious means—and ultimately, its “dullness” of tone and design worked in the committee’s favor. Edwin J. Cohn, the head of Harvard Medical School’s department of physical chemistry, praised that “restraint, which is likely to be more effective than the more often encountered aggressive statement.”

Few would have been able to disagree—or even agree—with Cohn: only 310 visitors ever saw the display in 1936. (The person who ran the exhibit’s front desk noted regretfully that “business was rotten.”) The reprints, however, remained in use as reference materials at Radcliffe, and today are archived in Schlesinger Library.

The significance of “Women in Science” accordingly lies more in its legacy than its Tercentenary reception. Decades before public attention turned with fervor to the excavation of buried stories of historical women in science, Radcliffe women were collecting these women’s names and work themselves, and fashioning them as dull, commonplace, and unremarkable in their production of “outstanding” scientific work.