He was the eldest son of a shoemaker turned Universalist preacher. When he was 15, his father died, but his father’s message, “the gospel of inclusion”—that God loves us all, asking us to do the same for others—became his life mission. He became the sole support of his mother and five younger siblings, working in a store, as a teacher, a bookkeeper, while studying Latin, Greek, French, and German. At 17, he wrote a friend of mixed race, explaining transcendentalism. “Starr,” as everyone called him, was arguably clearer than Ralph Waldo Emerson, who lectured on the subject.

At 18, he became the principal of a Boston-area high school, thanks to a colleague of his father, and at 20, he took his father’s pulpit in Charlestown. The older members saw him only as an overgrown boy—he was small in stature—yet he had a deep voice, a sharp mind, and rhetorical skills that rivaled the best. He published learned essays. He introduced himself to the Boston literati: Longfellow, Emerson, and Theodore Parker, the Unitarian transcendentalist and abolitionist who coined the phrases “government of the people, by the people, and for the people,” used by Lincoln at Gettysburg; and “the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” as paraphrased by Dr. King. Parker met Starr at 19, called him “a capital fellow,” and gave him use of his extensive library.

At 23, he left his father’s pulpit for that of a dwindling Unitarian congregation in Boston; many members had left to follow Parker. Starr King revived it, repeating the quip that the only difference between Universalists and Unitarians was that the former “thought that God was too good to damn them, while the latter felt themselves too good to be damned.” Unitarian Harvard then awarded him an honorary A.M. in 1850, when he was only 26. Yet with a wife and child to support, as well as his mother and a disabled brother, he had to supplement his salary on the lyceum circuit. Parker and Emerson often recommended him to speak on “Substance and Show,” “Socrates,” or a dozen other topics. He would go anywhere, he said, for “F.A.M.E – Fifty dollars And My Expenses.”

But he was exhausted, and already showing signs of TB. He often sought relief in upland New Hampshire. In 1859, he published The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscape, and Poetry, then sought a new post.

In early 1860, he accepted a call from the Unitarians in San Francisco, a struggling and isolated outpost in a state nominally “free,” but dominated by pro-slavery Democrats. Arriving in April, he quickly attracted throngs, enabling him to pay off the debt on a church building seating 1,000. Soon that was too small. Jessie Benton Frémont, daughter of a U.S. senator and wife of Colonel John C. Frémont, the 1856 Republican candidate for president, embraced him for preaching Unionism on a nonsectarian basis. At the Frémonts’ home, overlooking Alcatraz, Starr met the city’s thinkers, writers, artists, and naturalists. One was a young congregant, the writer Bret Harte, who had spoken out against recent massacres of Native Americans. He also met the pioneering photographer Carleton Watkins. Frémont, trying to revive gold mining on his ranch in the foothills below Yosemite, had hired Watkins to take pictures to entice investors.

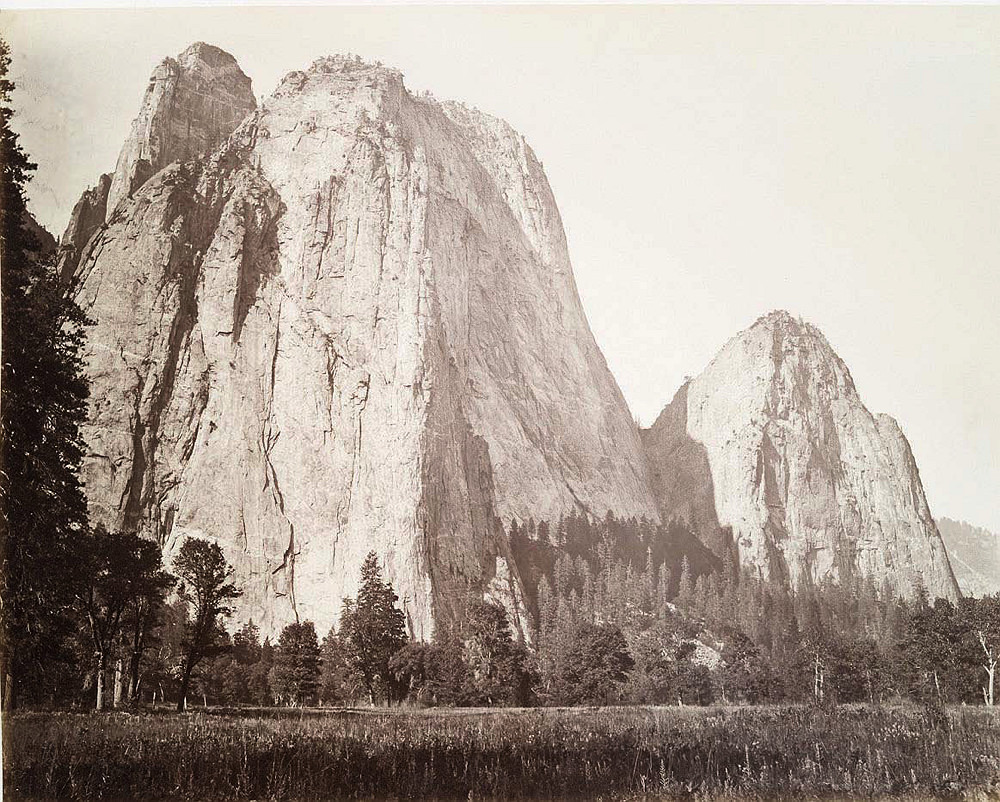

Photograph from Agefotostock / Alamy Stock Photo

Starr King went to Yosemite for a more spiritual purpose. He returned to speak about “Yosemites of the Soul.” Transcendentalism had come to the West. He published 37 letters about California in the Boston Evening Transcript. In his preaching, he held up both the Good Book, with its stories of liberation from slavery and of love transcending even suffering and death, and the Book of Nature, with its enduring witness to eternal renewal and re-creation. And he would do something rarely acknowledged: he saved Yosemite. He asked Watkins to photograph the valley. Not easy! The apparatus was huge; the technology, primitive. The results, spectacular! Hoping to preserve those vistas, Starr King sent prints to influential friends back east. Two Watkins images still hang in the Emerson House in Concord.

He is said, also, to have “saved California for the Union” with his lecturing. This is no exaggeration. Lincoln won California’s four electoral votes by 734 ballots, with 34 percent of the vote. When secession came, Starr King raised more money for humanitarian relief during the Civil War than anyone else in the nation. His congregation became the most influential in the state, building for him a Gothic cathedral at the heart of San Francisco, on Union Square (which he had named).

But in 1864, already worn down by TB and his exertions, he contracted another infection. He died that March, at 39. Ten thousand people crowded Union Square for his funeral. Abraham Lincoln, when told of his death, openly grieved. That summer, in the midst of civil war, Congress passed the Yosemite Bill, setting aside the valley in perpetuity as a park where the public could commune with Nature, almost as a memorial to Thomas Starr King.

Mountains are named for him, both in New Hampshire and in Yosemite. An African American historian has called him “perhaps the only truly anti-racist white Californian of his time.” For 75 years, a statue of Starr King represented his adoptive state in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, until a 2007 vote of the California legislature, under Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, replaced it with a statue of Ronald Reagan. As one Republican legislator said at the time, “I don’t even know who he was. Most people don’t.” Perhaps more of us should.