Growing up in Cambridge and wandering the wilds of Fresh Pond in the late 1800s, William Brewster scanned the trees and shoreline for signs of fluttering wings, listening for even the faintest peeps, tweets, and coos of avifauna. “It’s a phenomenon among a certain slice of people,” says Amy Montague, director of Mass Audubon’s Museum of American Bird Art, in Canton, “that they just fall madly in love with birds when they’re young.” This single-minded avocation sustained Brewster throughout life, and ultimately helped lay the foundation for the fledgling field of ornithology.

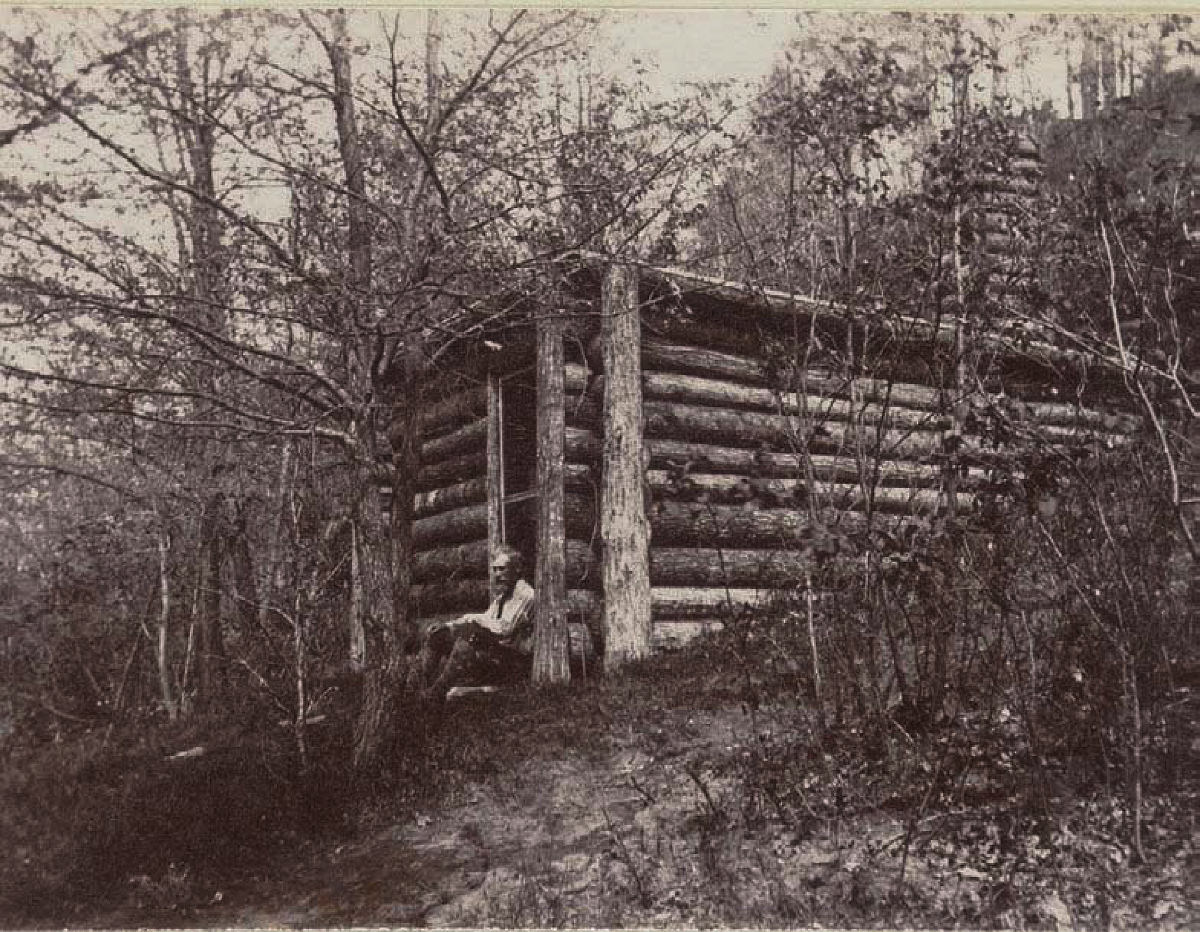

Brewster’s log cabin brought him closer to the birds.

Images courtesy of the Museum of American Bird Art/Mass Audubon

Frailty and poor eyesight reportedly prevented the boy from advancing past high school. Yet freed from the dictates of formal education and the need to make a living (his father was a wealthy banker), Montague notes, Brewster “devoted himself with academic rigor to his passion for recording in minute detail everything he saw and learned about birds not only in his journals, but through photography.” Mass Audubon, of which he became the first president in 1896, holds 2,000 of Brewster’s glass plate negatives, and Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (where he worked as a curatorial assistant and bequeathed his more than 40,000 bird specimens) has his photographic prints, along with hundreds of his journals, scrapbooks, and scientific articles. Many focus on observations made at October Farm, an estate of 300 woodland acres and a circa 1740 farmhouse he owned along the Concord River. The tract became his experimental field station, where he augmented wetlands to attract new species and built a waterside log cabin and canoe shelter “because he wanted to wake up hearing birdsong,” she says.

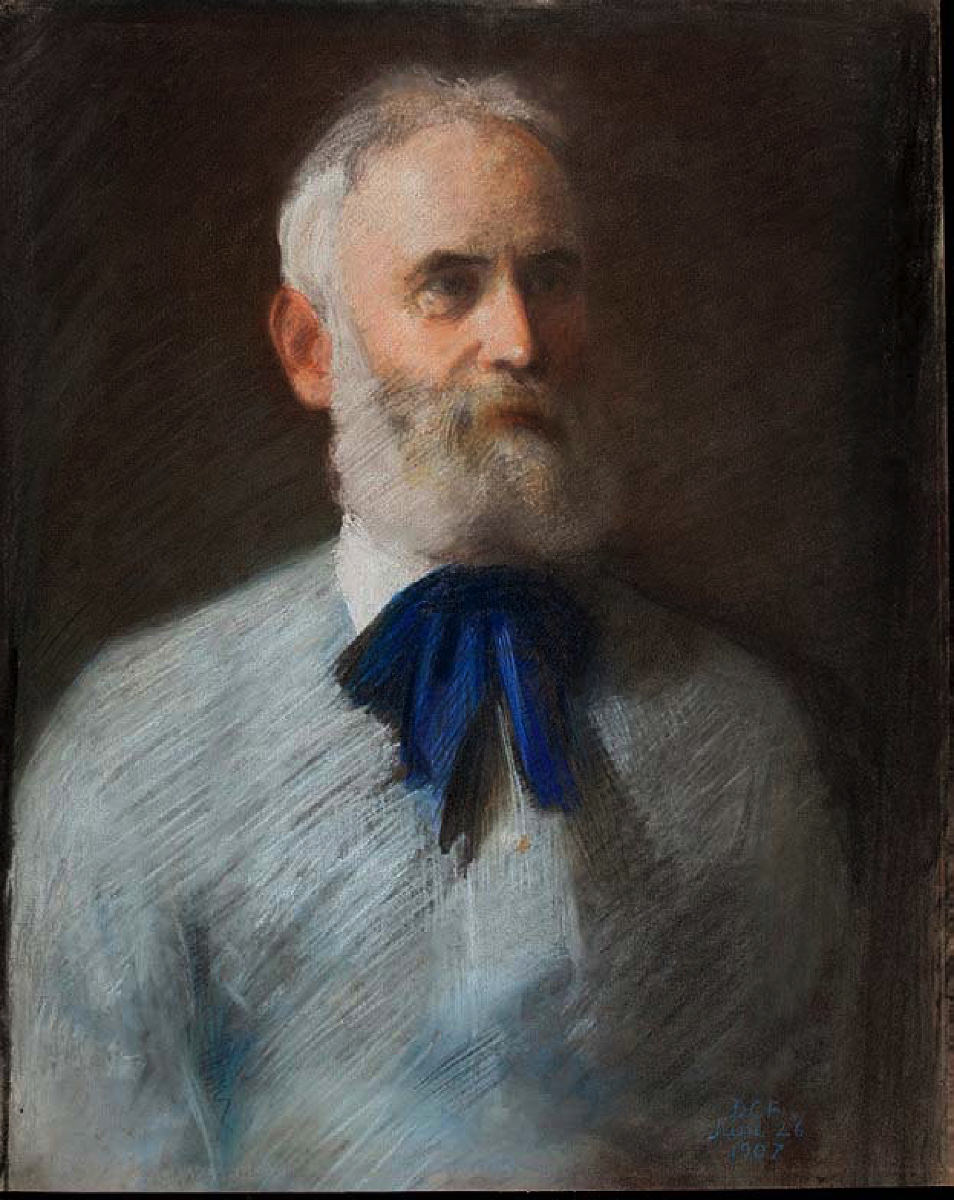

Portrait of William Brewster by his lifelong friend and fellow bird-lover Daniel Chester French

Images courtesy of the Museum of American Bird Art/Mass Audubon

The data he collected were pored over by his naturalist friends, like the sculptor Daniel Chester French (creator of the seated president scupture at the Lincoln Memorial as well as the John Harvard statue). Brewster also drew early members of two organizations he was instrumental in founding: the Nuttall Ornithological Club (which began in 1873, met at Brewster’s Brattle Street home, and drew many MCZ-affiliated members), along with what became the American Ornithological Society. Although Brewster collected his specimens by shooting them—it was considered the only way to study creatures before the advent of binoculars—by 1890 he had disavowed the practice on October Farm, where he was known to treasure even the smallest creatures. A 1920 memorial tribute in the ornithological journal The Auk notes that Brewster, when told that birds and squirrels were stealing the crops, just smiled and shrugged, replying, “All right; remember next year plant more; plant enough for all of us.”

In 2019, a century after Brewster’s death, nearly half of his former Concord land was donated to Mass Audubon as a new wildlife sanctuary. To celebrate that, and Brewster’s abiding spirit and influence, Mass Audubon and the Concord Museum have jointly mounted “Alive with Birds: William Brewster in Concord,” on display through September 5. Bird artis paired with his journal excerpts, and a mesmerizing video shown on four large panels chronicles the flora, fauna, and life of trees throughout the seasons in what’s been re-christened Brewster’s Woods. Two trails are open, and renovations of several buildings are planned. Also check the Concord Museum website for related events.

This still photo from the exhibit’s entrancing video taken throughout the four seasons in Mass Audubon’s new Brewster’s Woods Wildlife Sanctuary features, from left: a mourning dove, Northern mockingbird, Canada geese, and Savannah sparrow.

Images courtesy of the Museum of American Bird Art/Mass Audubon

The 143-acre tract was donated by Nancy Beeuwkes, who lives with her husband, Reinier Beeuwkes ’62, Ph.D. ’70, on adjacent land in what was Brewster’s farmhouse base of birding explorations. As late as May 1919, two months before he died, Brewster was there, as his last journal entry reveals, taking in the sights and sounds. “Cloudless, windless and of summering warmth, the day was simply perfect….When I awoke at daybreak a Crested Flycatcher was calling in the orchard. At breakfast time and later a rare-voiced Wood Thrush was winging in the run. Besides these were the usual Oriole, Pheobe, Bobolink, Purple Finch, etc.,” he wrote, “altogether a glad choir of delightful bird music.”