Photographs by Jim Harrison unless otherwise indicated. Objects © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Here begins an excursion through Harvard collections in search of evidence of the vernal equinox. The first sign is found in the collected pages of this magazine. "Cambridge Spring," by the late Primus I, a.k.a. David McCord '21, L.H.D. '56, appeared in "The College Pump" in the issue of April 26, 1941. War loomed, but the birds and the bees knew nothing of that.

"As quick as you can say 'Littauer Center' the buds on local bushes in the Yard uncurled last week, and a man with a spading-fork got himself into difficult areas behind the shrubbery and set to work on the good earth. Cambridge spring is a fleeting and only half-expected miracle. A day of comforting warmth, a touch of the south wind, and there it is, whether we deserve it or not. This year it has come earlier than in the memory of living man--so we may speak of it. The little band of English sparrows that behaved to us so pleasantly all winter, reporting daily to the unofficial feeding station under a secluded Wadsworth House window, have taken themselves off in search of new eaves and cornices. Their manner as yet is noisy but not arrogant. Squirrels have an uncombed, late-rising, but independent look. Only the pigeons still ask openly for bread....

"Overnight the forsythia turned yellow and flowered; and tomorrow it will shed. The Japanese crabapple has issued its ultimatum. The leaves of the lilacs are an inch long....At the moment a large bee doing figure eights has steered his way to our quarter of the Yard, and his little music--if we could hear it--would be enough to make us put the period here where we shall drop a colon: Do you remember Cambridge spring? The young gentleman across the way at his window in Grays, his white shirt very laundered in the sun, is reading. He is probably reading sociology, oblivious of the bee, the forsythia, the Japanese crabapple, and the fact that he will soon be older and remembering in turn. Sociology? It is doubtful if he knows that three black-crowned night herons flew over Cambridge last evening heading north."

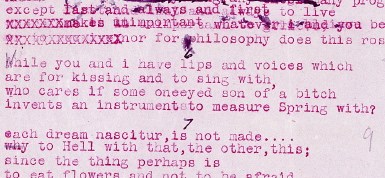

| For a grittier take on spring, we head ourselves to Houghton Library, the College's storehouse of rare books and manuscripts, and to the papers of Cambridge-raised, Harvard-educated, poet e.e. cummings '15. The typescript of cummings's "voices to voices, lip to lip" contains this mention of the season.

|

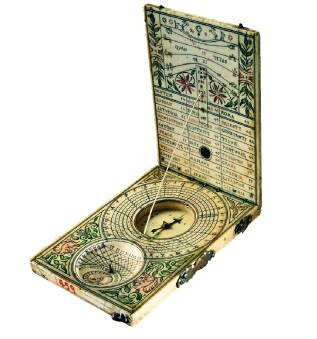

An instrument to measure spring with. Plunging into the basement of the Science Center, we find the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Among its treasures is an ivory pocket sundial (its gnomon missing) made in 1613 in Nuremberg, Germany, by Lienhart Miller, that enables the user to know precisely when spring arrives and exult accordingly. When the shadow of the sun follows the horizontal line near the top of the upright, that day is the equinox. The dial was designed also to predict the weather--impending April showers, for instance--and provide quantities of information about far-flung places useful for folk longing to go on pilgrimages. |

A familiar spring chorister in the East in woods near water is Pseudacris crucifer crucifer, a tree frog. Although only three-quarters of an inch to an inch and a half in length, the peeper emits a high-pitched whistle with an occasional trill that carries far. A glee club of spring peepers heard from a distance can sound like sleigh bells. The distinguishing feature of the species is the rough "X" on its back. The drawing is from "Notes on the Peeping Frog," by Mary H. Hinckley, in Memoirs of the Boston Society of Natural History (1884) at the Ernst Mayr Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. |

The magnificent frigate bird normally breeds in the tropics of the New World, but this one has alluringly inflated its throat sac like a Valentine at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. Amorous frigate birds may be spotted off the coasts of Florida, the Gulf states, and southern California. They seldom alight except to nest. |

The fossil fly shown here, actually tiny, is an extinct species of the modern genus Plecia, the love bug. This individual lost interest in romance some 50 million years ago. "It dates from what might be called the springtime of spring," says Brian Farrell, professor of biology and curator in entomology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, "the time when the world's climate was much less seasonal than today." A species of the fly's descendants blackens the highways of Florida in spring in mating swarms of zillions of individuals. "Many love bugs meet their Maker," Farrell notes, "when they slam into the windshields of cars at 50 miles an hour, in copula." |

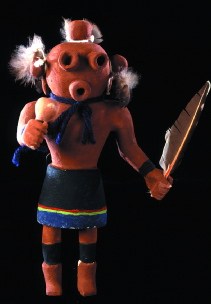

Hopi mudheads are spirit beings. The best-known of them is Tatsiqtö, represented here in a five-and-a-half-inch high Hopi doll made in Arizona, probably in 1937, of painted wood, yarn, and feathers, and now resident at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Several hundred spirit beings, katsinam, once visited the Hopi in person, but now they come as clouds for part of each year, and costumed Hopi men assume their powers in ceremonies and dances. Katsina dolls are given to infants as teaching aids. Mudheads, made of mud, symbolize the matrix where humans originated. In the knobs on their heads, they carry seeds and soil collected from human footprints. As the Hopi begin to plant their gardens in April, mudheads are among the all-important rainmakers from the gods (see the on-line exhibition of that name at www.peabody.harvard.edu/katsina). Remember e.e. cummings's "in Just-", also at Houghton: "in Just-spring when the world is mud-luscious...when the world is puddle-wonderful...." |

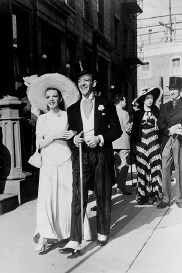

| The Venerable Bede asserted in the eighth century that Easter was named after Eostre, a Saxon goddess of fertility whose festival was celebrated on the vernal equinox. Other scholars have implicated the Norse goddess Ostara, whose symbols were the hare and the egg. Today, the Easter Bunny visits with a basket of eggs, promising fecundity and regeneration, and then it's time for a parade in one's new bonnet. Here, from the Theatre Collection, are the proudest couple, Judy Garland and Fred Astaire, in a still from the 1948 movie Easter Parade.

The rabbits gamboling through the initials "F.L.H."-- for Frances L. Hofer, for whom artist Marie Angel did her 1960 painting on vellum--are in the care of the Department of Printing and Graphic Arts, Houghton Library. |

Courtship, abduction, sacrifice--Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring has it all as Slavonic elders watch a maiden dance herself to death to appease the god of spring. The Harvard Theatre Collection houses this watercolor costume design by Nikola(breve)l Konstantinovich Rerikh showing two foot-stomping clowns in the 1913 premiere in Paris by the Ballets Russes. |

The polychrome nosegay on this Turkish dish of the late sixteenth century is jolly looking but may be a lover's lament. In Ottoman poetry, the cypress tree, center, often symbolizes the tresses of the beloved, the carnation means the beloved is aloof, and the tulip stands for unrequited passion. The dish and its messages, about a foot in diameter and crafted in Iznik, ancient Nicaea, east of the Sea of Marmara, speak now at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum. |

This once-buzzing bee did its business with these flowers (an extinct relative of hibiscus) about 53 million years ago. Now an object of scholarly interest at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, it is the second oldest fossil bee body in captivity, according to Bruce Archibald, doctoral candidate in entomology, who is at work with a colleague on a paper describing and naming the species based on this type specimen. (The oldest bee body, from Late Cretaceous amber of New Jersey, is perhaps 15 million years older and "isn't as cute," says Archibald.) | ||||||

An unknown Chinese master captured this pristine tree-peony blossom in ink and colors on silk during the Southern Song period, 1127-1279. From the Sackler Museum. |

Why spring happens. When Hades snatched the maiden Persephone from a flower-strewn meadow and carried her down to the underworld to be his wife, her mother, Demeter, goddess of agriculture, heard her daughter's screams and raced to help her, but in vain. Demeter wandered the earth, mourning greatly. She caused a vast barrenness to fall upon the land. Flowers withered, grain died. A delegation of gods urged Demeter to relent and come to Mount Olympus, but she remained on earth, inconsolable. At last Zeus saw that he himself must intervene and dispatched Hermes to the underworld with instructions. Hades knew he could not resist and relinquished Persephone, but he persuaded her first to eat a few pomegranate seeds, which obliged her to return to him. Hades has Persephone for four months of each year and then releases her topside. Spring accompanies her return. Persephone appears on the obverse of this Sackler Museum silver coin, struck at Pheneos, in Arcadia, Greece, circa 362 B.C. to 300 B.C. |

This burst of apple blossom is glass. It is one of 4,400 models comprising the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants, the University's most-visited tourist attraction, at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. The famous glass flowers are fragile and elderly, and a conservation effort is planned. The first 1,000 models, including this one, have been taken from their cases and await the development of a conservation lab and conservation team to undertake an estimated 15,000 hours of treatment. |

Spring training. Even Red Sox fans get hopeful in the spring. When this shot from the University Archives was made of the Harvard squad taking batting practice in the spring of 1898 (the year this magazine was founded), spirits no doubt ran high, and at season's end the team had won 21 games, tied 1, and lost only 10. (Never mind that they lost two of three games with Yale.) |

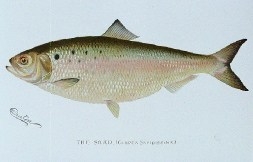

Fictional detective Nero Wolf recognized spring by consuming quantities of shad roe, prepared by Fritz the chef with a sauce of fresh sorrel in cream. The American shad, a member of the herring family, is an anadromous species: it leaves its offshore salty habitat in spring to swim up its natal fresh-water river to spawn. In southern rivers, it dies after spawning; north of the Carolinas, increasingly it survives, until in Maine 75 percent of spawners return to the sea. Shad reach the Charles River (albeit now only a few thousand of them, though the Merrimack River has an excellent run) in May, just as the Amelanchier arborea, or shadbush, unfurls its pendulous racemes of small, white flowers in joy at their return. The American shad averages three to five pounds, and a female may carry 125,000 to 525,000 eggs. The flesh of the fish is edible, certainly, but boney. This drawing of Alosa sapidissima, at the Ernst Mayr Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, is from First Annual Report of the Commissioners of Fisheries, Game and Forests of the State of New York (1896), where it accompanies a survey of shad in the Hudson. |

Spring cleaning gets going with Pearline Washing Compound, as seen on "My Busy Day," an 1892 advertising trade card from the Historical Collections of the Baker Library, Harvard Business School. |

Coming soon. Blossoms, by the British artist Albert Joseph Moore (1841-1893), emerges from the dark vaults of the Fogg Art Museum to bring this celebration to a rapturous but refined conclusion. |

"Spring Sampler" conceived by Christopher Reed, executive editor, and executed by Jennifer Carling, art director.