Greater cost-consciousness will become a part of Harvard's culture in much leaner University budgets for fiscal year 2005, beginning on July 1. Interviewed in her Massachusetts Hall office on the September day when the Boston Globe reported "MIT to cut budget, may lay off 200," vice president for finance Ann E. Berman took pains to distinguish Harvard's approach from that of peer institutions, which have imposed spending freezes, halted construction, and laid off employees following three years of endowment losses. But at the same time, the University's chief financial officer made clear that some of Harvard's goals are the same. "Our endowment resources," she said, "allow us to be thoughtful and strategic about this, rather than having an across-the-board cut."

|

| Ann E. Berman |

| Stephanie Mitchell / Harvard News Office |

Harvard's concerns, Berman said, are "not triggered by any one event or issue. It's about many more things"one of which clearly is the economic environment. Although Harvard's endowment recovered strongly in the year ended last June 30, after two years of modest declines, the annual report on investment results unusually highlighted the relative decline in endowment purchasing power since 2000 (see "Rebounding Returns"). During fiscal year 2003, the "spending rate" (funds distributed divided by endowment value at the beginning of the year) rose to 5.15 percent, at the upper limit of the Corporation's goal, and the highest level in two decades. (Income provided from the endowment includes about $770 million for academic operations, and $80 million for a special limited-term assessment for the costs of assembling land in Allstontogether, much the largest source of University revenue.)

Berman also cited constraints on sponsored-research funding, the University's next most important source of revenue. Grants from the National Institutes of Health, the principal source for Harvard, are leveling off, she said, and "Some people probably aren't worrying enoughit's not automatic that Harvard's brilliant faculty will get an increasing piece of that smaller pie."

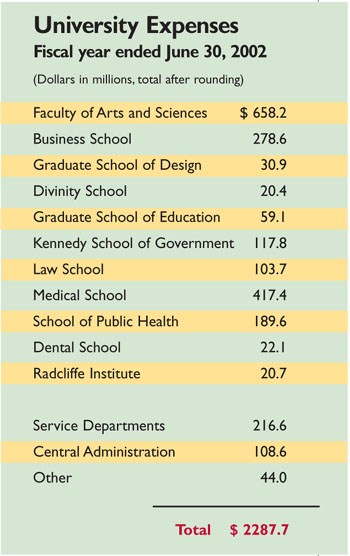

Intersecting with those limits on income are factors that propel spending. Although Harvard's annual financial report is published after Thanksgiving, Berman disclosed that expense growth in the fiscal year ended June 30 again outpaced revenue growth. (In fiscal year 2002, expenses rose 10.8 percent and revenues 5.8 percent; see "Tighter Times," January-February, page 58.) The "most striking" factors were higher healthcare and pension costs. Space and occupancy costs also rose as new facilities opened. Utilities were "dramatically" higher, reflecting energy prices and the cold winter.

|

In this context, four issues make timely "a strategic review of what we are doing" to enhance efficiency and control costs. First, Berman noted, alumni donors and other supporters regularly ask, "How do I know that the University is well managed?" That interest becomes more important as the University plans its next capital campaign (see "Brevia"). Second, families are struggling with escalating tuition bills. Third, given the priorities President Lawrence H. Summers and Provost Steven E. Hyman have enunciatedinvestments in curricular revision, public service, life sciences, and the future Allston campus"We want to be able to say we are pushing as many of the resources in that direction as we can." Finally, after the years of growth enabled by the University Campaign and strong endowment returns during the late 1990s, a review of accreted "nice to do" functions is warranted.

That review is taking place in three concentric rings from Massachusetts Hall, encompassing central administrative functions, University services (dining, facilities, and so on), and the schools.

The administrative and service categories, comprising about one-third of a billion dollars of Harvard expense (see chart), are more immediately under Berman's "influence and control" than the autonomous schools. She hopes to realize savings by sorting out what functions might be done better, or not at all. Rather than setting a numerical goal for expenses or personnel, central administrative units have been asked to prepare alternative 2005 budgets level with current spending and 5 percent smaller. If adopted, either course would force some downsizing or abandonment of functions, given the likely increase in employee-benefit costs.

The service units are undergoing what Berman called "peer review," asking their University customers whether they would prefer cost savings that might accrue from curtailed service. At the same time, she said, the staff will examine outsourcing (to realize lower costs available on the market) and opportunities to reduce internal unit costs from gains in volume (perhaps achievable if the schools combined back-office or service functions). All proposals will be reviewed by a task force, vetted for impacts on customers, and winnowed for the 2005 budget by next spring.

Extending across the University, Berman said, the central administration seeks further savings from new purchasing agreements (like those in place for office furniture, computers, travel, etc.) for photocopiers and for paper. Larger savings are being pursued for big-ticket building-related expenses, including systems, supplies, and construction.

The financial pressure on the schoolspersonnel costs, tighter research funding, greater student need for financial aidcomes internally through the endowment spigot. After double-digit boosts in the endowment distribution earlier in the decade, the faculties have geared down to 2 percent increases for two years now. The Corporation will not set the fiscal year 2005 distribution until late autumn, but Berman said signals are being sent: "We've been a bit more pessimistic. We've said, 'We're thinking about zero.'"

In response, there have been publicized reductions in staff at the Kennedy School, Graduate School of Education, and Radcliffe Institute; rumors of reductions at the Harvard University Art Museums; proposed savings in the library system from reducing services at Hilles; and still "more happening by attrition," Berman said, plus decisions not to fill empty positions and deferral or cancellation of future capital projects.

Looking ahead, Berman "would love to see revenue increase faster than costs" by the time the books are closed on fiscal year 2005. Given the time required to reach purchasing agreements and have users adopt them, she forecast that goal would more likely be realized in the following year. A realistic aim, therefore, is for revenue and expense to grow only in tandem in the year that begins on July 1an outcome that clearly requires a change from recent Harvard spending habits.