Fifty years ago, American support for the death penalty was as low as it has ever been: more Americans opposed it than approved it. Violent crime in the country was low. The number of executions annually was a small fraction of the historical peak in the 1930s. These conditions set the stage for the modern era of the death penalty in the United States.

In 1972, the Supreme Court struck down the penalty as it then existed, voiding statutes in about 40 states plus the District of Columbia. Under those laws, juries had wide latitude to impose a death sentence, with no restrictions or standards to guide them. They imposed the sentence rarely yet randomly: they sentenced people to death who were convicted of relatively minor crimes like robbery as well as those found guilty of murder. When the Court struck down those laws, Justice Potter Stewart wrote that juries were imposing the death penalty “so wantonly and so freakishly” that the punishment was cruel and unusual under the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment.

Stewart and many others thought the Court had ended the death penalty in the United States, but the ruling provoked a defiant backlash: 35 states passed new death-penalty laws. In 1976, the Court struck down new state laws that made a death sentence mandatory for anyone convicted of a capital crime. But the Court upheld laws that supposedly gave discretion to juries and judges about whether to impose a death sentence, with guidance about how to exercise their discretion.

It is common to view this reinstatement of the death penalty as the height of U.S. hypocrisy about human rights, with the nation saying yes while most of the rest of the world was saying no: 140 countries have abolished it in the decades since the United States revived it. In 2015, the nation ranked fifth among countries with the death penalty in the number of prisoners it executed, behind China, Iran, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. But the revival was something new in American law and unprecedented in any country, a distinct alternative to abolition and retention. It was an experiment in regulation by the Supreme Court.

A new book by Jordan Steiker and Carol Steiker reflects a generation of joint legal scholarship on capital punishment.

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Decades of evidence lead to the conclusion that the experiment has failed badly—and the evidence continues to mount. Many states have imposed the death penalty in ways that discriminate by race and geography, with relatively few counties responsible for a large share of American death sentences and executions. Countless juries have been confused about how to weigh critical evidence in capital cases, like whether they should regard proof of a defendant’s intellectual disability as a reason not to impose a death sentence, or a reason to do so. Thousands of trial courts have made serious legal mistakes on their way to imposing a death sentence and have been reversed by appeals courts. Thousands of lawyers unprepared for the demanding nature of the work have given slipshod counsel to people charged with capital crimes.

Most dramatically, 156 people convicted beyond a reasonable doubt and sentenced to death have later been exonerated. One state after another has botched execution by lethal injection, leading to excruciating pain for those being executed and a growing sense that states cannot properly carry out the only form of execution that a majority of Americans have said is acceptable.

The death penalty is enormously costly. An authoritative study in California underscored the high expense of prosecuting capital cases, defending people charged with capital crimes, and housing people on death row: between 1978 and 2011, when the state executed only 13 people, the total cost of administering the death penalty there was $4.04 billion.

Of the 8,124 people sentenced to death between 1977 and 2013, according to the Justice Department, only 17 percent were executed. Six percent died by causes other than execution and 40 percent received other dispositions, including reversals of their convictions. The rest—37 percent—were in prison. In California in 2014, a federal judge found that, of the 748 inmates then on the state’s death row, more than two out of every five had been there for 20 years or longer.

In 2009, the American Law Institute—the most prestigious organization in the country engaged in improving the law—removed the death penalty from the options it had long recognized that states could choose from to punish a convicted murderer. The institute is a nonpartisan group of about 4,000 judges, scholars, lawyers, and others. In The New York Times, Adam Liptak reported the group’s reason for abandoning capital punishment: “the capital justice system in the United States is irretrievably broken.” In a year of notable developments about the death penalty, including its repeal in New Mexico, he wrote, “not one of them was as significant as the institute’s move.”

The genesis of that change was the strong sentiment among the institute’s membership to formally oppose capital punishment. Lance Liebman, then its director, turned to the sister-and-brother team of Carol S. Steiker ’82, J.D. ’86, RI ’11, and Jordan M. Steiker, J.D. ’88, for counsel. They were “the most influential legal scholars in the death penalty community,” wrote criminal-justice scholar Evan J. Mandery in his book A Wild Justice, about the major cases that shaped the current penalty. Liebman commissioned them to write a report addressing this question about American justice: “Is fair administration of a system of capital punishment possible?”

In a dense, erudite, airtight report, they answered no. But they also recommended that the institute not declare its opposition to the death penalty: that “could possibly undermine the authority of the Institute’s voice on this issue,” they warned, because the position “might well be understood to reflect a moral or philosophical judgment” and “there is deep disagreement along these dimensions regarding the basic justice of the death penalty.”

Instead, they advised the group to issue a statement “calling for the rejection of capital punishment as a penal option under current circumstances (‘In light of the current intractable institutional and structural obstacles to ensuring a minimally adequate system for administering capital punishment, the Institute calls for the rejection of capital punishment as a penal option.’). Such a statement would reflect the view that the death penalty should not be imposed unless its administration can satisfy a reasonable threshold of fairness and reliability.”

Even a provisional rejection of the death penalty proved too contentious for the institute. At the meeting when it made this decision, the chief justice of the Utah Supreme Court pointed out that if the group rejected the penalty, it would create “a problem for those of us who must adjudicate these cases” because “this is above all a highly charged political issue.” But the group accepted the rest of the Steikers’ advice. It announced that it would no longer include the death penalty among the punishments it provided guidance about for the states.

In the past seven years, the report has played a quiet yet decisive role in helping shift debate among scholars and policymakers about the death penalty. The focus has moved from whether the penalty is just, which cannot be answered empirically, to an emphasis on whether states apply it fairly and consistently, which can. The Steikers’ approach shaped the policy of America’s most respected legal organization. With its imprimatur, their report has influenced decisions of people who shape American law.

Since the report, six states have abolished the death penalty, most recently Delaware in the summer of 2016, bringing to 20 the number of states that do not have it. Of the 30 that do, 14 are not carrying out executions because of a formal or an informal moratorium. Only 17 states have executed any death-row inmates in this period—including Delaware, before it abolished the punishment. Just six states have executed more than 70 percent of those inmates. One of those states, Oklahoma, now has a formal hold on executions during an investigation of its method of lethal injection. The death penalty is in flux in most of the states that still have it on the books.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer cited the Steikers’ report in a widely discussed dissent he wrote in a 2015 Supreme Court case. Joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, he said for the first time in one of his judicial opinions that it was “highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment.” In reaching that conclusion, Breyer emphasized “changes that have occurred during the past four decades.”

In that period, executions resumed at a slow pace and then accelerated, reaching 98 in 1999. Since that apex, the annual total has dropped sharply, to 28 in 2015. The number is on track to be smaller in 2016. These days, the country imposes the death penalty as capriciously as it did in 1972, when the Court struck down the penalty for being as unpredictable as a lightning strike. In his dissent, Breyer wrote that “the Court should call for full briefing on the basic question” of whether capital punishment is still acceptable under the Constitution. It is due for a reckoning before the Court.

Preamble to the Reckoning

The Steikers’ new book, Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment (Harvard University Press), summoning their joint decades of work on the subject, is a preamble to that reckoning. They explain conclusively the problems of the American death-penalty system and why the Court’s regulation has not fixed them. There is not much difference between the core of the conclusions in the book and in their report, yet the book has an historical breadth and an explanatory power that take it far beyond that earlier assessment.

It is a commanding account of a judicial intervention that has given many Americans false confidence in capital punishment as a fair and consistently applied criminal sanction. In reality, despite hundreds of rulings—including those that have eliminated the death penalty for youth under 18 and for the intellectually disabled, and that have said it should be used to punish only the worst of the worst murderers—the Supreme Court has not corrected the many and serious ways it works badly.

The Court has said repeatedly that the sole justifications for capital punishment are the roles it plays in deterring murder and in exacting retribution. The Steikers show how the death penalty fails to serve either purpose. The very large discrepancy between the high number of people sentenced to death and the relatively low number executed takes away the penalty’s deterrent force. The generally long delays between the imposition of death sentences and the subsequent executions, and the conversion of many death sentences into life sentences (so that more than three-fourths of all death-row inmates gain a second life) takes away its retributive power.

Courting Death makes a devastating case. It is the most important book about the death penalty in the United States—not only within the past generation but, arguably, ever—because of its potential to change how the country thinks about capital punishment. It has the insight, vision, and authority to help resolve one of the most divisive social issues of the past half-century. It demonstrates mastery of a prodigiously intricate, often bewildering body of law, and the ugly but revealing history to which the law is linked.

A condemned inmate at San Quentin

Eric Risberg / Associated Press

The East Block entrance to death row at San Quentin

Eric Risberg / Associated Press

Guarded exercise cages at San Quentin

Eric Risberg / Associated Pres

The Steikers acknowledge what they call “the profound difficulty of regulating a controversial practice across the vast and diverse country in light of the independence that our federal system affords each state.” Yet Courting Death argues firmly that, having set rules about the administration of the death penalty under the Constitution with which many states have not been able, or willing, to comply, the Supreme Court should decide that capital punishment is unconstitutional since many states have not carried it out constitutionally.

The most striking testimony the Steikers present comes from five Supreme Court justices, appointed by Republicans as well as Democrats, who at one time voted in favor of the death penalty and, based on what they learned as justices about the miscarriages of the death-penalty system, changed their minds, either while still on the bench or after they retired.

They are Lewis F. Powell Jr., Harry A. Blackmun, and John Paul Stevens, plus Breyer and Ginsburg. Adding in William J. Brennan Jr. and Thurgood Marshall, who were well known for opposing the death penalty on moral grounds, the Steikers wrote that seven justices have “explicitly stated that they think capital punishment should be ruled categorically unconstitutional.”

When the Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, Marshall repeated in a dissent what he had written four years earlier in the case striking down capital punishment laws—that he believed “the American people know little about the death penalty, and that the opinions of an informed public would differ significantly from those of a public unaware of the consequences and effects of the death penalty.” This idea is known as the Marshall hypothesis.

Social-science studies testing the hypothesis have yielded contradictory results, including one study whose results support the antithesis: researchers gave pro death penalty information to death penalty opponents and a smaller number of them remained opposed. The Steikers write: “for many people, emotional or cultural influences on death penalty attitudes outweigh purely cognitive input.” Nonetheless, a purpose of their book is to prove Marshall right.

Both Steikers clerked for Marshall, in the twenty-first (Carol) and twenty-third (Jordan) years of his 24 as a justice, before he retired in 1991. As they wrote, “Marshall was the only justice on the Court who as a lawyer had represented defendants in death penalty cases; he retained a fierce interest in the topic as a justice, which we both inherited as a result of our experiences in his chambers.”

Before clerking for him, neither had thought much about the death penalty. After their clerkships—moral as well as legal apprenticeships with the justice who spoke most powerfully for the powerless, including those on death row who had good reason to think it was unfair that they were there—both made it the passionate focus of their vocation. The Steikers have become the most influential legal scholars on the death penalty by working closely together on this project for the past 24 years.

Sibling Scholars

Carol, now 55, is 18 months older than Jordan. She was a year ahead of him through the public schools where they grew up in Cheltenham Township, outside Philadelphia. She has a photo of them at ages 10 and a half and nine looking like jubilant co-conspirators. Their brother, James (18 months older than Carol), a corporate, pension, and tax attorney and financial adviser near Philadelphia, blazed the family trail into the law as a public-interest scholar at New York University Law School, to the initial dismay of their father, a pediatrician. He viewed lawyers as foes who made trouble by filing baseless medical-malpractice lawsuits. Their mother was a school psychologist who became an administrator of special-education programs in a neighboring school district. Courting Death is dedicated to their parents as their “first teachers.”

Carol, a French and English history and literature concentrator, graduated Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude and then spent a year on a Fulbright grant as a teaching assistant in a lycée in Grenoble, France. Following James, Jordan went to Wesleyan, graduating Phi Beta Kappa and magna cum laude in 1984, in philosophy, with awards in debate and oratory as well, and then spent a year teaching high school in Vermont. At Harvard Law School (HLS), both Carol and Jordan made the Law Review—Carol was only the second woman to lead the publication in its then 99-year history. Both graduated magna cum laude. After their clerkships—moral and legal apprenticeships—both Steikers made the death penalty the passionate focus of their vocation.

After clerking for Marshall, Carol worked for four years as a trial lawyer at the Public Defender Service in Washington, D.C., representing indigent clients at all stages of the criminal process. Jordan went straight from his clerkship into teaching at the University of Texas School of Law, in Austin, in 1990. His courses cover capital punishment and constitutional law. Though he trailed her through school, she trailed him as a professor, starting at HLS two years later. He also got tenure before she did and took delight in reminding her of that. “Hello, this is Professor Steiker calling,” he would say when he phoned. “Is this Assistant Professor Steiker?”

Soon after the assistant professor arrived back at Harvard, a student editor at The Yale Law Journal asked her to help the publication solve a problem. A book review had fallen through and the Journal needed something to fill that slot. Carol could review any book she wanted, as long as she turned in the essay in four weeks. She called Jordan to ask if this was worth doing, when she was teaching for the first time and had a year’s worth of criminal-law and criminal-procedure classes to prepare. He told her it was a stroke of luck for a rookie scholar to get an offer of guaranteed space in a major journal, and, since he was on a writing leave, suggested they write the review together. He proposed an essay about a book that both had read: Crossed Over: A Murder, A Memoir by the novelist and short-story writer Beverly Lowry.

A hit-and-run driver had killed Lowry’s 18-year-old son. In trying to sort through her feelings about her son’s killer, she was drawn to the case of Karla Faye Tucker, then on death row in Texas for a double murder she had helped commit eight years earlier as a 23-year-old. (Tucker was executed in 1998.) Lowry examined Tucker’s life and the aspects that possibly warranted life in prison with no possibility of parole, rather than the death penalty. The book is based in part on a series of conversations they had when the author visited Tucker in prison. Lowry later described her as “maybe the most loving person I have ever met.”

Jordan went up to Cambridge so he and Carol could work side by side. They talked about what they wanted to say, made a detailed outline, divvied up the writing, and edited each other’s drafts. One day in her office they aired out their differences as they had when they were kids: they yelled at each other. It was a vacation week and they assumed no one else was around. “When we walked out after this,” Jordan recalls, “to our horror, one of her colleagues in the office next door had his door open, and we just burst into laughter at the idea that this completely out-of-control, child-like fight had been clearly witnessed by one of her colleagues, and this was her first year teaching at Harvard.”

In that first piece, the Steikers wrote:

For Lowry, the relevance of Tucker’s life to her crime is a deeply unsettling issue. If the circumstances of Tucker’s life call forth forgiveness and mercy, then must Lowry forgive the unknown killer of her son Peter? But if the circumstances of Tucker’s life should not qualify our reaction to her crime, how can Lowry understand and justify her deep attachment to Tucker, and her even deeper attachment to her own troubled son? Lowry recognizes that these questions lie at the heart of her relationship with Tucker: “Forgiveness is at issue, mercy, the right of one human being to hold another accountable, and to judge.”

The review was the first of 26 substantial scholarly articles and book chapters they have written together, not counting their new book—roughly one major piece a year, in addition to pieces each has written solo. They wrote a lot of the book during the 2014-2015 academic year, when Carol was a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. That fall, Jordan was a visiting professor at HLS, teaching Carol’s capital-punishment course while she was on leave. That also made it easier for them to collaborate.

The book reflects habits that they developed writing primarily, until now, for a scholarly audience. They sometimes lapse into professional shorthand (such as “standardless discretion,” meaning discretion not limited by any standards or principles) likely to puzzle general readers and, in some places, even readers steeped in law. (When they asked me to read a draft of their book, I encouraged them to get rid of the jargon by running their draft through a hot typewriter, as pre-computer-age editors used to say to writers. After they finished revising, Jordan emailed me, wryly and accurately, that they “ran the manuscript through a moderately warm typewriter.”)

Despite its academic tics, however, the finished book reflects their shared powers as first-rank teachers and advocates as well as scholars: it is lucid, conceptually ambitious and discerning, and full of nuanced judgments that add up to a highly original view about the history, workings, and consequences of the death penalty. Courting Death deserves to become a legal classic.

The Steikers have each produced well-regarded bodies of work aside from their death-penalty scholarship. One of hers is about criminal procedure. The other is about the roles of dignity and mercy in the criminal-justice system. Twenty years ago, for example, she explained why seemingly irreconcilable views about Supreme Court rulings on criminal procedure were both correct. Some Court-watchers were saying that, under Chief Justice Warren E. Burger and Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, the Court had repudiated landmark rulings made under Chief Justice Earl Warren. Others insisted there was no counter-revolution.

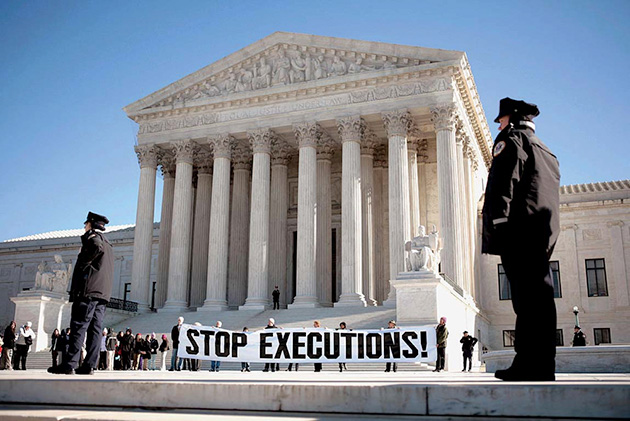

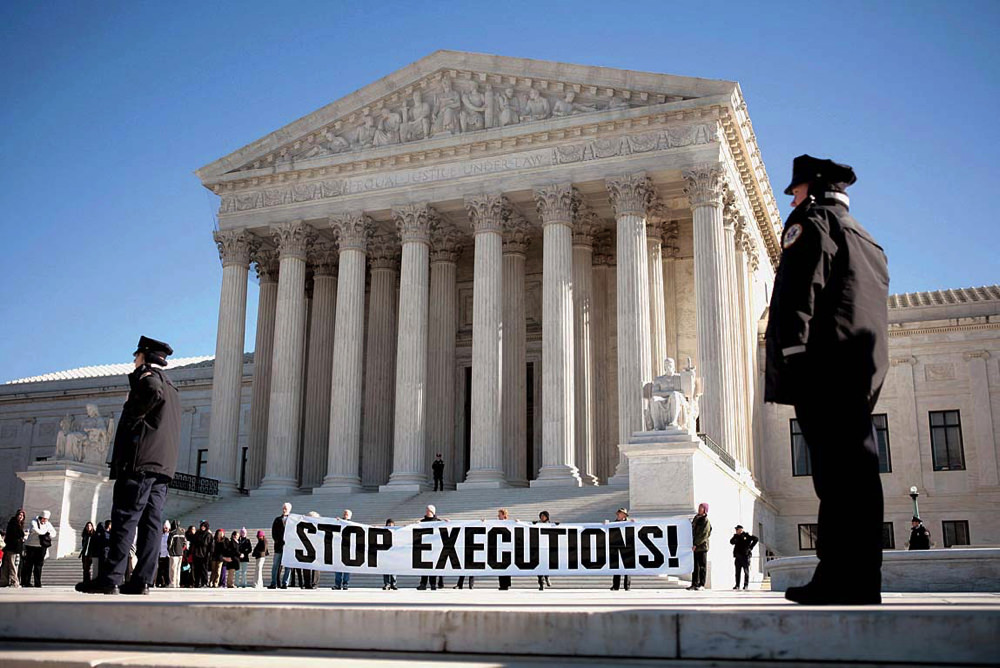

A protest before the U.S. Supreme Court, 2007

Jason Reed / Reuters / Alamy

A pre-execution vigil, St. Louis, 2014

Jeff Roberson / Associated Press

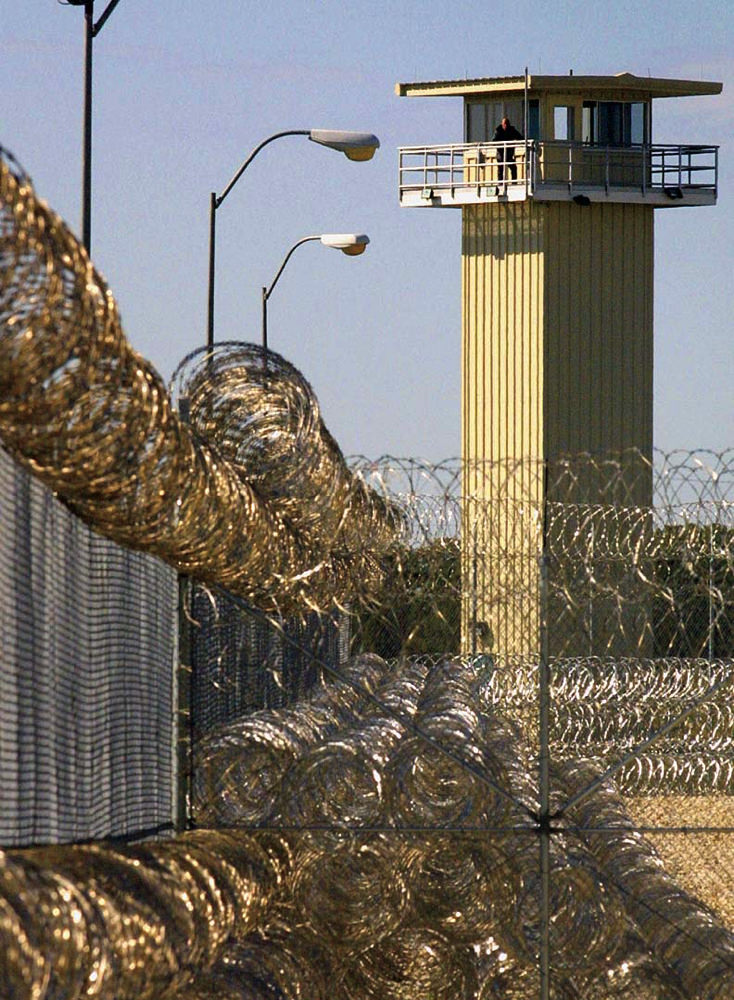

Death-row guard tower, Livingston, Texa

Richard Carson / Reuters / Alamy

She explained that the Court had maintained well-known rules of conduct—say, the exclusionary rule, barring evidence obtained in an illegal police search—yet had changed little-known rules of decision, like courts admitting illegally obtained evidence gathered under a “good-faith exception” (as when police think they have a valid warrant from a judge that turns out to be invalid). In that way, she judged, the Court had “profoundly changed its approach to constitutional criminal procedure since the 1960s.”

Today, in addition to being Friendly professor of law, she is a faculty co-director of HLS’s new Criminal Justice Policy Program and special adviser on public service to Martha Minow, the school’s dean. As a young professor, Minow supervised Carol’s major student research paper, “The Constitutional Status of Sexual Orientation.” Published in 1985 as a student note in the Law Review, it made a pioneering and widely cited argument in favor of same-sex marriage.

“What most amazes me about Carol,” Minow told me, “is the ease with which she moves across and fully integrates technical doctrinal knowledge, philosophic arguments for mercy, deep historical understanding, and savvy coalition-building. She is brilliant and compassionate and draws on both strengths to advance the use of law for the most fundamental social change.”

One part of Jordan’s independent work focuses on how Congress and the Court have severely cut back the writ of habeas corpus, the once-robust, now-weak means for prisoners to challenge their detention. That shift is a pitiless legacy of the law-and-order era, built on the often mistaken premise that the criminal-justice system operates fairly but needs to speed up the process of finding guilt and carrying out punishment. “She is brilliant and compassionate and draws on both strengths to advance the use of the law for the most fundamental social change.”

Another part looks at the role of racial discrimination in constitutional law. He has an abiding interest in the contradictory significance of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed segregation in public schools. It is often called the most important decision of the twentieth century, yet is criticized by legal scholars, including Jordan, because “the substantive commitments of Brown are notoriously elusive.” The Court’s opinion in that case was brief and sketchy, leaving to the future the hard questions about how to bring about desegregation.

Now holder of the Parker endowed chair in law, Jordan is also director of his law school’s legal clinic, the Capital Punishment Center. His Texas Law colleague, William E. Forbath, who holds the Bentsen chair in law and is associate dean for research, told me, “He’s incredibly deep at both scholarship and advocacy. He has always had a keen eye for broader themes that explain the workings of the death penalty. He has always been a leader in efforts to reform, discipline, and constrain use of the death penalty in Texas.”

Between 2004 and 2007, the clinic had six victories in Supreme Court cases. Jordan was lead counsel in two and co-counsel in three, with Robert C. Owen, now a clinical professor at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law. In one of the cases, Jordan made the winning oral argument at the Supreme Court against then Texas solicitor general, now Senator, Ted Cruz. In addition to filing many petitions to the Court and amicus briefs, seeking review of Texas death-penalty cases (sometimes with Carol as co-counsel), he has helped train a generation of anti-death-penalty lawyers.

Both have done noteworthy work on their own that helps explain why together they have made abolition of the death penalty their mission. Jordan’s is an essay called “The Long Road Up from Barbarism: Thurgood Marshall and the Death Penalty,” written when he was a young professor. A common view of Marshall is that his brilliance in law was best suited to the work he did as director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, in the storied line of cases culminating with Brown, which he argued in the Supreme Court. As Jordan wrote, “Justice Marshall’s greatest asset was his ability to expose the distance between the noble assurances of the law as written and the uncomfortable reality of the law as applied.” Jordan went on, “he is rarely credited with his ability to translate his lawyering skills into accomplished judging.”

As a justice, however, Marshall did that in monitoring whether, while states were administering the death penalty, they were meeting the standards set by the Court. Jordan wrote, “He scrupulously examined every petition for certiorari filed by a capital defendant to assess whether the sentence had been constitutionally secured. While many Justices would vote on a petition for certiorari”—a formal request that the Court hear a case—“based on a quick reading of the questions presented and the arguments supporting review, Justice Marshall often insisted that the full record of a capital case be delivered to his chambers so that it could be scoured for misleading jury instructions, prosecutorial misconduct, or other constitutional errors.”

What Marshall did to national fanfare as a lawyer he did with little public notice as a justice. He and his law clerks built a record documenting why, in death-penalty cases, as Jordan wrote, “the Constitution cannot be construed on the basis of abstractions alone.” Marshall taught that it is vital to follow legal rules while seeking justice: traditional, even conservative, in ways that most did not see, he believed in the perfectibility of institutions through law. Most states that carried out executions a quarter of a century ago did so at night. When an execution was scheduled, the Justice had one of his law clerks remain at the Court to receive the petition for a stay of execution. Marshall always voted for the stay, yet never directed his clerk to record that vote until the petition arrived.

Carol’s most revealing work is a series of writings about philosophy of criminal law, including in the Oxford Handbook on that subject a chapter called “The Death Penalty and Deontology,” about the view in philosophy that we are obligated to act according to a set of principles, regardless of the consequences (deontology comes from the Greek word for duty). She wrote that “extremely brutal forms of punishment,” including the death penalty, “require the public to suppress their ‘civilized’ responses of unease and revulsion in the face of overt brutality and pain and replace them with the feelings of satisfaction and celebration that the rituals of criminal justice are designed to elicit.”

This is the most abstract of Carol’s scholarship, yet in a way the most personal. It is about what motivates her death penalty work—“some fundamental discomfort, revulsion, and moral indignation,” as she told me: “This is straight up moral philosophy, about why I thought the strongest argument against the death penalty was that having that practice in our society works against the human capacities of empathy and compassion that are important for moral judgment and are essential for moral choice. If you have to harden yourself collectively, steel yourself to take the life of other people, over time a society will wear away at these human capacities, because who we are and what we’re able to do and be is shaped by the societies that we live in and our public choices.”

Mapping Executions

In the United States today, the Steikers explain, the difference between the 30 states that have the death penalty and the 20 that do not is less important to understand than the difference between the “symbolic states” that impose a large number of death sentences while carrying out few and the “executing states” that impose a large number and carry out a relatively high percentage. In symbolic states, the rate of imposing death sentences is sometimes higher than in executing states.

Pennsylvania is a symbolic state: it has executed only three people since 1976, and each chose to die by halting his appeals. Texas is an executing state: it has executed 537 people since then. But the rate of death-sentencing in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, is higher than in Harris County, Texas, which has had more defendants executed than any county in the country.

The symbolic states of Pennsylvania and California have executed about 1 percent of the people they have sentenced to death. The executing states of Texas and Virginia have, respectively, executed about 50 percent and about 70 percent of those they sentenced to death. “Executions require a very high level of coordination and cooperation among governmental actors,” the Steikers wrote, “and such coordination is evident in only a small number of jurisdictions.”

The coordination depends on motivation. Politics accounts for the difference in both, in symbolic and executing states. The former are almost all blue states where support for the death penalty is limited and, in places, opposition is strong, as in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania and San Francisco and parts of Los Angeles in California. The latter are almost all red, where support is widespread and sometimes intense. The generally low standard of quality required of lawyers who represent defendants in capital cases is especially disturbing.

The federal death penalty is also symbolic, in a nation made of blue and red states. Since Congress reinstated the federal death penalty in 1988, 75 people have been sentenced to death for federal crimes. Three have been executed. No constituency pushes for more prosecutions and executions under the federal death penalty, yet none pushes hard for its abolition. Some of the federal crimes punishable by death are crimes against patriotism: terrorism, treason, espionage, and murder of an important federal officer like the president, in addition to genocide and large-scale drug trafficking, among other offenses. If the Supreme Court abolishes capital punishment in the states, the Steikers wrote, abolition of the federal death penalty is likely to follow in stages—for most federal capital crimes and, eventually, for terrorism and treason.

The political benefits of carrying out executions are higher in red states than in blue ones. To the extent there are benefits from support for capital punishment in blue states, they are strongest at the local level. A prosecutor can quell outrage about an awful murder by bringing capital charges against the murderer and securing a capital conviction. If the execution is delayed or does not happen, there is little or no political cost to the prosecutor: he or she can reap the benefits from favoring capital punishment by winning a death sentence.

But this use of the death penalty for its symbolic value has “enormous and senseless material cost,” the Steikers continued. The complexity of capital cases makes them expensive for the prosecution and for the defense. The informal mutation of death sentences into life sentences makes imprisoning death-row inmates especially expensive for states. For those inmates, the psychological cost can lead to “death row syndrome”—uncertainty and fear about when execution will come, reinforced by the almost intolerable conditions of solitary confinement or imprisonment in similarly debilitating conditions.

The sentence, Judge Cormac J. Carney wrote about the death penalty in California, “has been quietly transformed into one no rational jury or legislature could ever impose: life in prison, with the remote possibility of death.” Symbolic states have created conditions parallel to those that led the Supreme Court, in 1972, to strike down death-penalty statutes in the United States—except that, then, it was death sentences imposed rarely and randomly and, now, it is executions that are seldom carried out. The death penalty in those states is largely a pretense, with relatively minor political benefits compared to the huge and wasteful costs.

The situation is worse in executing states, however, because of the nature of the Court’s regulation. To constrain states’ use of the death penalty, the Court has developed four major legal doctrines: narrowing, requiring states to limit the kinds of murders for which the punishment is death; proportionality, limiting the types of criminal offenses and offenders the death penalty applies to; individualized sentencing, calling for states to provide a way for jurors to consider mitigating evidence about the offense and the offender and not to impose a death sentence; and heightened reliability, requiring states to use extra legal safeguards in capital cases because the finality of execution makes the death sentence different from all other criminal sanctions.

But the Court’s enforcement of this regulation has been minimal and some states’ flouting of it has been maximal, leading to what the Steikers called “extensive, disruptive litigation.” The Court ostensibly narrowed the kinds of murders for which death is the proper punishment by requiring that a jury find there was an aggravating factor to a murder. Yet most of the states that passed new death-penalty laws after 1972 included as a factor that “the murder was especially heinous, atrocious or cruel, manifesting exceptional depravity,” a catch-all that was broad and subjective enough to cover any murder and did not narrow the kinds of murders for which death was the punishment. In Georgia, a detailed study found, 86 percent of people convicted of murder during the five years after the state’s new law went into effect were eligible for the death penalty.

Despite the doctrine of heightened reliability, the Steikers showed, there are “numerous contexts in which capital defendants receive no special safeguards.” One of the most disturbing is the generally low standard of quality required of lawyers who represent defendants in capital cases. A defendant who brings a claim of ineffective counsel must prove, according to the Supreme Court, that the lawyer’s performance was “outside the wide range of professionally competent assistance” and that his or her errors “actually had an adverse effect on the defense.” This lax standard long undermined defenses in capital cases. Beginning in 2000, the Court made three decisions that reversed convictions in capital cases, based on inadequate counsel. “These decisions are important,” the Steikers wrote, “but they illustrate the Court following rather than leading the transition to acceptable capital lawyering.”

The Steikers concluded that the Court’s regulation “has left us with the worst of all possible regulatory worlds. The resulting complexity conveys the impression that the current system errs, if at all, on the side of heightened responsibility and fairness.” But “the last four decades have produced a complicated regulatory apparatus that achieves extremely modest goals while maximizing political and legal discomfort.”

The minimal regulation has led to extremes represented by the death-penalty systems in California and Texas. California, with only 13 executions since 1976, had 747 people on death row as of September 2016,the largest such population in the country. Texas, with 244 people on death row as of July, has executed almost two out of every five of the 1,437 people executed in the United States since the death penalty was reinstated, almost five times as many people as Oklahoma, with the second highest number of executions.

“The most significant variable affecting execution rates,” the Steikers wrote, “is the speed at which cases move through state and federal systems of review.” The main gates through which a case must move are the defendant’s appeal of his conviction and sentence; any claims he makes in state court based on new facts in the case; his challenge to the state proceedings in federal court; and the setting of a date for the execution.

Texas, more than any other state, has “embraced procedures and practices which tend to clear the path to execution and move cases expeditiously.” California, at the other end of the spectrum, has insisted on treating each step in the legal process as a means to ensure that the conviction was accurate and the sentence fair.

A part standing for the whole in this divergence is the extremely different expectations that those states have of lawyers who represent defendants on appeal. In Texas, death-row inmates get assigned counsel soon after being sentenced to death, but there is generally a “lower standard of practice,” in the Steikers’ words. Reflecting that low standard and low expectations, despite the life-or-death consequences, “lawyers representing death-sentenced inmates often decline to travel to Austin,” where the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals sits, to make an oral argument about the appeal, “in their sole opportunity to assert many claims.”

In California, lawyers must meet rigorous requirements to qualify as counsel in death-penalty appeals and demand for them is much greater than the supply. As a result, appeals “languish for years in the state system,” the Steikers wrote. Once counsel is engaged, “capital appellate attorneys would never consider waiving their oral argument in such circumstances (and the California Supreme Court would likely not permit them to do so).” Even California’s page limit for briefs in capital cases indicates higher expectations: it “is more than twice the limit in Texas.” In Texas capital cases, counsel is appointed, the case is briefed, and the appeal is resolved “within a few years of a death sentence. In California, those events routinely require well over a decade.”

While the legal process varies among states that have the death penalty, the Steikers concluded that “a fairly consistent big picture emerges: symbolic states are far more likely to have what could be termed ‘due process’ legal cultures.” They “necessarily” delay and often “ultimately” defeat those states’ efforts to carry out executions: “it is nearly impossible for any state to provide sufficient resources to allow its capital processes to maintain both a high rate of death sentencing and a high rate of execution while simultaneously conforming to a due process model of adjudication.”

In Texas and other executing states, the opposite of the due process model is the “legacy of a much older and broader phenomenon,” the Steikers wrote. It is “the result of southern resistance” to the effort of the Supreme Court “to impose national values of racial justice.”

Racialized Justice

When the Court struck down state death-penalty statutes in 1972, the lead counsel in the case and the lawyers most responsible for convincing the five justices in the majority worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the law firm of the civil-rights movement. In one of its Court filings, the Fund explained, “The long experience of LDF attorneys in the handling of death cases has convinced us that capital punishment in the United States is administered in a fashion that consistently makes racial minorities, the deprived and the downtrodden, the peculiar objects of capital charges, capital convictions, and sentences of death.” Almost half a century ago, the death penalty was an urgent civil-rights issue. The penalty was almost abolished in 1972 because of grave concerns about racial discrimination.

Today, that fact seems to come out of nowhere. It contrasts baldly with the jurisprudence about the death penalty. That law is largely about legal procedure (dividing a capital trial into a stage for considering guilt and, if the defendant is convicted, a second stage for deciding punishment) and takes little account of racial discrimination in the administration of capital punishment. The Supreme Court was so eager to avoid confronting the discrimination in this area of law that, in 1977, when it decided a case about the death penalty for a man convicted of rape, it chose to outlaw the penalty as excessive for the crime and mentioned neither race nor racial discrimination. That belied the record in the case, which included that, of the 455 men executed in the United States for rape between 1930 and 1967, 405, or almost nine out of 10, were black—almost all convicted of raping white women.

The Steikers approach this immense inconsistency as a puzzle that must be solved to fully understand capital punishment in America. William Forbath said, “This book shows Jordan and Carol as scholars at the top of their form, and that’s about as high as it gets.” They see the Court’s logic: a generation after Brown, the justices were still contending with the backlash to integration of public schools in contentious cases about school busing, for example, and with other controversial racial issues, like affirmative action. The death penalty was explosive enough without adding race to the mix. Yet race has shaped capital punishment in the United States. “It is simply impossible to understand where, why, and how the death penalty persists in the U.S. without looking at racial politics and culture.”

As Jordan put it, “It is simply impossible to understand where, why, a nd how the death penalty persists in the U.S. without looking at racial politics and culture. Despite the Constitution’s guarantees of equal protection of the laws, due process of law, and freedom from cruel and unusual punishments, the Court’s constitutional regulation of capital punishment was unable to cure the long-standing racial pathologies of the American death penalty.”

The story began with slavery and the use that slave owners and other whites made of brutal public executions as object lessons, to maintain control over other slaves. “Slaves convicted of murdering their owners or of plotting revolt,” the Steikers wrote, were often subjected to “terrifying and gruesome forms of execution such as burning at the stake or breaking on the wheel,” where the slave was lashed to a large wagon wheel and his limbs were beaten with a club, with the wheel’s gaps allowing the limbs to snap.

The story carried on with lynchings of blacks in the Jim Crow South. They wrote, “The lynching ritual (sometimes called ‘lynchcraft’) often involved long-abandoned punishments such as branding, eye gouging, and the cutting off of ears.” In the early twentieth century, southern advocates of the death penalty contended that it was essential to keep execution as a legal punishment to reduce the number of lawless lynchings. (“As one Tennessee politician argued in opposition to abolition,” the Steikers wrote, “‘if this bill should become law it would be almost impossible to suppress mobs in their efforts to punish colored criminals.’”)

The story persists with racial discrimination today, at every step of the legal process involved in the death penalty: in bringing capital charges, selecting jurors in capital cases, and sentencing convicted offenders to death, with the people sentenced to death and executed disproportionately poor, black, and male. The race of the victim is especially significant: those who murder whites, especially black offenders, are much more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murder blacks; and although young black men are much more likely to be murdered than people in any other racial or gender group, their killers rarely face the death penalty.

The Steikers are not the first to tell parts of this story. They are quick to credit the scholars whose work they build on. But they recount with singular effectiveness the haunting role that race continues to play in death-penalty cases, almost always without acknowledgment by the Supreme Court. Capital punishment in the South, where four out of every five executions have taken place since the Court reinstated it in 1976, was a way for whites to terrorize blacks legally in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Vestiges of that vigilante justice still mark death-penalty systems in the South. This strand of the Steikers’ writing should change forever how general readers understand the history and role of capital punishment in the United States.

An inmate after exercising, San Quentin

Photograph by Eric Risberg/Associated press

Elsewhere in the world, country after country has abolished the death penalty out of respect for human dignity. Here, if the Court finally abolishes it, Americans may mistakenly think that the justices did so for the same reason. But in choosing not to reckon with the role of race and racial discrimination in the American use of the death penalty, the Supreme Court has chosen not to take account of that ferocious form of racism. That is a fundamental injustice. If and when the Court buries the death penalty, the Steikers surmise, it is likely to omit acknowledgment of this “original sin,” which has stained capital punishment since the era of slavery.

For that reason, Courting Death is a feat of remembrance as well as a guide to resolution. The Steikers explain why, for the most pragmatic of reasons, the Court should end capital punishment in the United States. But an integral part of the book is their account of what the country should never forget about the racial pathologies of the death penalty. Those pathologies provide an indelible moral basis for abolishing it, as well.