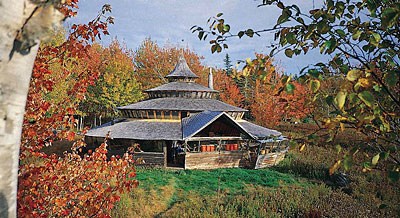

"Build a yurt with Bill and you witness his educational ideas in action. The yurt is his philosophy made visiblesecurity, nonviolence, simplicity, experimentation, activism, cultural blending, reverence for place, and beauty. He will not build a yurt for you (that would be tantamount to commodification of an educational experience), but he will work with you to build a yurt," writes John Saltmarsh in his introduction to A Handmade Life: In Search of Simplicity, by William S. Coperthwaite, Ed.D. '72 (Chelsea Green Publishing, $35). Coperthwaite is a teacher, builder, designer, and writer who has lived for many years a self-sustaining life on Maine's northern coast, in Machiasport, eschewing grid electricity and plumbing and motors. This handsome book, with photographs by Peter Forbes, is part manifesto, part biography, and part instruction about how to build necessities such as a rain barrel. Before you decide where to live, consider these thoughts about "democratic architecture."

It may sound strange to talk of honest and dishonest houses. After all, aren't houses neutral, material objects? Yet if a house is larger than we can build and care for on our own, it could be regarded as violent, exploitative architecture.

The larger and more complicated the house we build, the more that house becomes a time-consuming luxury, requiring effort that could be focused on areas of greater need and worth.

Balance in this, as in all matters, takes judgment. Some people put in a disproportionate amount of time styling their hair, some spend hours on their car, some are obsessed with their tennis stroke, and some of us are inclined to spend too much time on our houses.

|

|

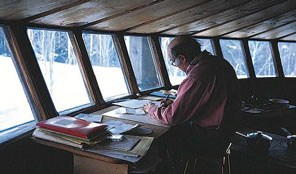

| Coperthwaite and his yurt, Machiasport |

Until there is a decent balance of basic necessities for all people, we are duty-bound not to waste time and energy on peripheral things. The modern yurt has been designed as part of the quest for a democratic architecturea shelter that people can take part in building for themselves. For this to be possible, it must be simple, take relatively little time to build, be aesthetically pleasing, low in cost, and easily cleaned and maintained.

There will not be one form of structure that answers the needs of all people. Climate, occupation, and taste vary too greatly for universal rules. We need to experiment with many designs using many different materials. And we need to design not for material gain but to create the best, most genuinely nonviolent architecture possible.

What are your requirements for a democratic house?