The news, reported in the November 14, 2002, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), sounded startling. C-reactive protein (CRP), detectable by an obscure, cheap blood test that measures inflammation in the body, seemed to predict cardiovascular disease better than cholesterol. Among 28,000 women followed for eight years, the 20 percent whose levels of CRP were highest were 2.3 times as likely to develop cardiovascular illness as those in the lowest quintile. The conclusion: identifying people with elevated CRP could allow "optimal targeting of statin therapy," since the statin drugs commonly used to lower cholesterol might also help those with high CRP readings. Enthusiastic reports followed in the New York Times, Boston Globe, and Washington Post, as well as in Time and Newsweek.

Careful dissection of the research, however, such as that provided in a recent Nieman Reports article, "Medical Reporting in a Highly Commercialized Environment," by clinical instructor in ambulatory care and prevention John Abramson '70, M.D., offers a less vertiginous view. The NEJM article, for starters, reported only differences in relative risk (2.3 times greater), omitting the benchmark of absolute risk. It turns out that the lowest-risk women developed about one episode of cardiovascular disease annually per 1,000 women. Hence those in the highest-risk group would see only 2.3 episodes annuallyjust 1.3 more per thousand women per yearthan those in the lowest quintile. Furthermore, the lead author of the NEJM article disclosed that he is "named as co-inventor on patents filed by Brigham and Women's Hospital that relate to the use of inflammatory biologic markers in cardiovascular disease."

|

| Chart by Stephen Anderson |

Such conflicts of interest have become widespread throughout clinical research in medicine, says Abramson, who spent two years as a Robert Wood Johnson Fellow learning to analyze and criticize research articles. "Seventy percent of clinical research is now funded by drug companies," he says. "Most clinical research is fundamentally commercial activityalbeit cloaked in the guise of public servicedesigned to maximize corporate profits." Commercialization as well as omissions and obfuscations like the absolute/relative risk comparison have produced a world in which "Doctors have to base their clinical decisions on scientific evidence, but the fundamental nature of that scientific evidence has changedit has become more like infomercials than objective science."

Abramson tackles this dilemma in a forthcoming book, tentatively titled Pretending to Care. Having worked for 20 years as a family doctor, he sees the American healthcare system as one in which "We talk a lot about prevention, but tend to treat disease downstream, at the end stage[which] happens to be the most profitable one." He notes that our system is "spectacular" on some issues"If you have a disease that is profitable to treat, the best place in the world to be is the United States"but in healthy life expectancy, "we rank twenty-second among 23 industrialized countries. The medical enterprise pretends to care about our health, but it cares much more about corporate well-being."

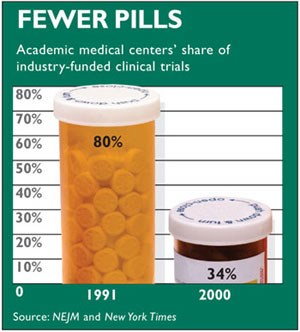

In recent years, Abramson says, "Things have changed radically." In 1991, universities and medical centers carried out 80 percent of the clinical research sponsored by the medical industry, but by 2000 that figure had fallen to 34 percent. Instead, contract research organizations (CROs)for-profit companies that the drug companies hire to do their researchhad taken over two-thirds of industry-funded clinical research. "The pharmaceutical houses exert great influence over research at CROs," Abramson says. "They design and carry out the studies, frequently withholding complete data even from the researchers responsible for analyzing and reporting the results. Studies with negative findings are far more likely to be delayed in publication, or not published at all." Abramson also notes that big advertising agencies are buying up CROs, as reported in the New York Times last November. "The function of this research is to sell productand who knows better how to do that than ad agencies?" he says. "They'll do it soup-to-nuts: design the research and sell the drugs."

Studies published in major British and American medical journals show that corporate-sponsored research is 3.6 to 4 times more likely to be favorable about the product than nonsponsored research. "We're getting a distortion of our medical knowledge," Abramson warns. "We look for new knowledge only in areas that offer the greatest potential return on corporate investment, while other knowledge is strongly suppressed."

Things have gone so far that two years ago, the editors of 12 leading medical journals, including NEJM, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and the Lancet, issued an unprecedented joint statement declaring that academic researchers had lost control of the design, execution, and publication of medical research, and that the fabric of the intellectual environment was consequently eroding. Unfortunately, the pronunciamento appeared the week of September 11, 2001. But even with better timing, Abramson says, "Bad news doesn't travel well in this area."

This commercialization of research directly affects patient care, Abramson says, because "doctors have been through medical boot camp, and they've been drilled to believe in the journals," Yet last year, even the august NEJM changed its policy to allow editorialists with financial conflicts of interest to discuss research in its pages. Medical specialties have guidelines that define indications for various drugs, but "80 percent of the people who write these guidelines are getting paid by the drug companies," Abramson notes, "and 59 percent are getting paid by the manufacturers of the very drug they are considering." For example, when a panel from the American College of Rheumatology recommended Celebrex and Vioxx for arthritis treatment, "All four doctors on the panel had financial relationships with at least one of the pharmaceutical companies involved," he says.

Abramson acknowledges that maximizing profit "is the job of private enterprise. But we're expecting private enterprise to do something it can't do and doesn't want to do. How do we get the marketplace to actually serve healthcare needs? That's the role of government watchdogsbut even the watchdogs have been drugged." The upshot, he charges, is an environment that makes it increasingly difficult for doctors to "help people connect with who they are, and what the roots of their health problems are"to practice "real medicine."

~Craig Lambert

John Abramson e-mail address: john_abramson@hms.harvard.edu