On a wintry Wednesday evening, Maria Mavroudi is delivering a lecture on Byzantine science. Using evidence from texts and artifacts, she sketches an alternate history, one that competes with the common account that the Byzantine empire’s inhabitants were less advanced than their contemporaries in their use and understanding of the sciences.

Mavroudi reports that Ptolemy’s Geography, which was produced in Roman Egypt in the second century A.D. and describes a system of coordinates similar to modern latitude and longitude, survives in 54 Greek manuscripts. She argues that the typical explanation of why the text was reproduced—merely to preserve it for future generations—is wrong, and makes a case that the real purpose was to produce a manual for contemporary use. She cites texts that describe the richness of Constantinople’s libraries, and others that mention wooden astrolabes; time and the elements, she says, may have erased the evidence of Byzantium’s use of scientific instruments made from this perishable material. Byzantine science, she says, has gone unacknowledged not because it did not exist, but because studying it requires such diverse expertise: knowledge of languages, of Byzantine history, of the history of science.

This research requires a particular breed of scholar. Mavroudi, Ph.D. ’98, who holds faculty appointments at Berkeley and Princeton, is one of them. She was the first person to earn a doctorate in Byzantine studies, per se, from Harvard; four different departments—history, classics, art history, and Near Eastern studies—were involved. And the setting for her lecture is the world’s foremost center of Byzantine scholarship: Dumbarton Oaks, an estate in Washington, D.C., which Harvard has owned since 1940, when Robert Woods Bliss, A.B. 1900, and his wife, Mildred Barnes Bliss, donated their Georgetown property to the University.

But it is not just in Byzantine studies that Dumbarton Oaks excels. It also has fellowship programs in pre-Columbian studies—focused on Latin America before Europeans arrived—and in garden and landscape studies.

The scholarly institute, with its research library, museum, and public gardens, encompasses such disparate academic pursuits by design. In the preamble to her last will and testament, Mildred Bliss wrote that the estate was to be preserved as a “home of the Humanities, not a mere aggregation of books and objects of art.” The place manages to incorporate the natural environment and the built environment; concepts of art and religion; cultural studies; and considerations of conquest and empire. It is a window into the past, but it reflects on the present.

These three seemingly unrelated fields do not just coexist at Dumbarton Oaks; they coalesce. Fellows toil in solitude in their offices, but they also emerge to discuss their projects with other fellows, and they discover parallels between fields. One past symposium investigated Byzantine garden culture; several current fellows’ projects have benefited from such cross-pollination.

For example, one of this year’s pre-Columbian fellows, University College London archaeologist Elizabeth Graham, is writing about the encounter between Europeans and the Maya, using evidence from excavations of the sites of two churches from the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, both in modern-day Belize. In conversations with Byzantine fellows, she has been struck by the similarities between early Christianity and the Maya version of Catholicism. “There’s no question that pre-Christian ideas have been incorporated into Catholicism,” says Graham. “It seems to me the Maya are just doing what all the European Christians did—they incorporate local culture with Christian sacred space.”

But to the disapproving Europeans, unaware that their own brand of religion was the product of a similar process, the pagan elements of Maya Catholicism looked foreign. “It’s interesting how, whenever there’s this meeting of two worlds, the one that becomes more powerful depicts the other one in a very simplified fashion,” Graham says. “I don’t think most of us realize that when we look at early records. We take them literally.” She sees parallels to this egotistical simplification of other cultures in various periods throughout history, including the contemporary world.

The project of another pre-Columbian fellow, Timothy Beach—a Georgetown University professor who teaches courses on climatology, hydrology, soils, geomorphology, and geoarchaeology—incorporates garden and landscape studies: he is investigating Maya agriculture and its impact on the environment. Beach earned his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota, and says the changes caused there by early European settlers are not unlike the effects of Maya agriculture: German farmers weren’t used to the steeper inclines and fast, hard rainstorms of their new home, and they took no precautions against erosion. In both central Minnesota and Guatemala, entire towns were buried under layers of eroded sediment.

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks

A bust of the Maya maize god, from the late seventh or early eighth century, appears in a display about Maya religion in the pre-Columbian wing.

Inquiries like these, in a sense, simply couldn’t take place without Dumbarton Oaks. The Renaissance brought a renewed interest in the Classical period; for a time, the millennia in between were forgotten, ignored. By bringing the Byzantine period to the forefront, the Blisses created a place for the study of all the periods, and of the major themes of human history.

Cornelia Horn, a professor in the theological studies department at St. Louis University and a current Byzantine fellow, is trying to trace the transmission history of apocryphal Christian texts during the seventh century. The nativity story appears not only in the Bible, but also in the Koran and in other texts that were not ultimately incorporated into these holy books. Horn’s project compares details in the different versions of the story in an attempt to get at which versions circulated when, where, and how widely. It is a study of a specific story’s evolution, but also of how Christianity and Islam influenced one another.

Geographically, the Byzantine empire was ideally situated to illuminate concerns that remain relevant today: interactions between world powers, for instance, or between religious traditions. A former Dumbarton Oaks director, medievalist Giles Constable, once said a stint there should be mandatory for all U.S. ambassadors sent to the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks

An openwork silver lamp, one of many items in the Byzantine collection from the “Sion Treasure,” liturgical objects and church furnishings from a sixth-century church site found in Turkey.

The Blisses were prescient in realizing the importance of Byzantine studies. Dumbarton Oaks welcomed its first Byzantine fellows in 1941, well before the field was widely recognized as a worthy academic pursuit. Alice-Mary Talbot ’60, who directs the Byzantine studies program, says that when she was studying classics in college, focusing on the medieval period “would have been unthinkable.” Today, she notes, the chair of the Harvard classics department is a Byzantinist; the previous chair, and current Dumbarton Oaks director, Jan M. Ziolkowski, also studies the medieval period. Talbot notes, with delight, that Maria Mavroudi won a MacArthur fellowship in 2005—a sign that the field has truly arrived.

The list of former fellows reads like a “who’s who” of Byzantine studies, and people tend not to come just once—Dumbarton Oaks keeps beckoning them back. Mavroudi’s first visit was in 1995, as a junior fellow, someone still working on a Ph.D. Her project was analyzing a Byzantine Greek book on dream interpretation and that book’s Arabic sources. In 2001, she returned to research bilingualism in Greek and Arabic in the Middle Ages. Mavroudi says these stints “proved formative for everything I did afterwards.”

Talbot, too, has kept coming back. She first fell in love with Byzantium during a fellowship in Greece, and a Ph.D. program in Byzantine history at Columbia brought her to Dumbarton Oaks for the first time, for a symposium in 1963. She spent a year there on a fellowship in 1966, and returned in 1984 to help edit the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, a project whose editorial home base was Dumbarton Oaks. When that project concluded, then-Dumbarton Oaks director Angeliki Laiou, whose professorship in Byzantine history at Harvard was endowed by the Blisses, appointed Talbot director of Byzantine studies.

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks

Alice-Mary Talbot, director of the Byzantine studies program

Today, Talbot’s office is in one of the Blisses’ guest bedrooms; the walls are lined with titles such as The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World; Byzantine Court Culture; Consent and Coercion to Sex and Marriage in Ancient and Medieval Societies; and Byzantine Magic. All were published by Dumbarton Oaks; the in-house press has helped shape Byzantine studies by issuing important texts and by supporting the writing of others with its fellowships. Dumbarton Oaks commissioned the translation of 19 hagiographies, never before translated into a modern Western language, and is publishing them as a series. Ziolkowski says he would like to see the press create a series of English translations of Byzantine texts, with the original Greek on facing pages, similar to the Loeb Classical Library and the Villa I Tatti Renaissance Library—both published by Harvard University Press, which produces, markets, and distributes Dumbarton Oaks publications.

Several current fellows are working on projects that will become resources for future scholars. Nadezhda Kavrus-Hoffmann, an independent scholar from New York who was a fellow last fall, is creating the very first catalog of Greek manuscripts from the Byzantine period in the United States: traveling among the libraries that hold the manuscripts and in some cases discovering texts whose existence had escaped notice. Current fellow Yuri Pyatnitsky, senior curator for the Byzantine icon collection at the Hermitage, in St. Petersburg, is creating a comprehensive catalog of that collection, incorporating information from recent analysis of the icons using new technical methods

Dumbarton Oaks also underwrites the development of Byzantine scholarship directly. Eustratios Papaioannou, another former fellow now translating the letters of Byzantine historian and philosopher Michael Psellos, is Dumbarton Oaks assistant professor of Byzantine studies in the classics department at Brown University. The appointment is jointly funded by the two entities, enabling Papaioannou to spend two years teaching at Brown and two years at Dumbarton Oaks conducting research. The Blisses’ gift has provided seed money for 11 tenure-track positions in Byzantine studies at nine U.S. universities during the past three decades. Dumbarton Oaks has also provided financial support for excavations and for the restoration of frescoes in a church in Cyprus. And it was at Dumbarton Oaks that the key to dating Byzantine coins was discovered.

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections

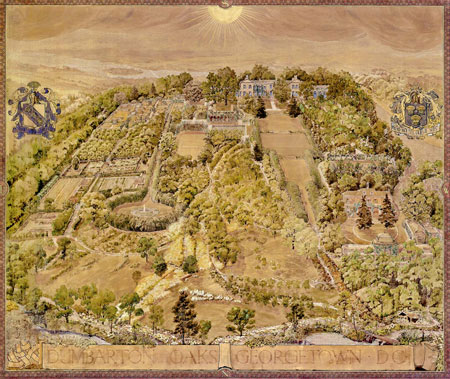

This watercolor gives an aerial view of the 53 acres the Blisses assembled to house art, scholarship, and memorable gardens. For many years, it hung over the fireplace in the music room. A copy hangs there now; the original is in storage to protect it from light—and other—damage. The painting was smudged, the story goes, when someone wiped a sponge down one side to clean it, not realizing that the colors would smear. Close observers will notice that, despite restoration, part of the left side of the image is less finely detailed than the rest. View a larger image.

Porter professor of medieval Latin Jan Ziolkowski began his tenure as director in September. Like the institute itself, he has diverse interests. His publications in the last two years include a book on the medieval precursors to fairy tales; one on the musical notation printed alongside the text of some medieval Latin poems; translations of a ribald story from the thirteenth century and of letters by the medieval French philosopher Peter Abélard, best known for his legendary love affair with Héloïse; and an 1,128-page volume titled The Virgilian Tradition: The First Fifteen Hundred Years.

“I like to think of myself as being a humanist who likes to work on the Middle Ages and on literature, but who has other interests,” says Ziolkowski. Medieval Latin texts are the starting point, but, he says, “I try to connect them in as many ways as I can to other literatures within Europe, and to other areas of study.” He has also chaired several interdisciplinary entities within the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, including the Committee on Medieval Studies and the Committee on Degrees in Folklore and Mythology. “A large part of my agenda in the first 25 years of my career,” he says, “was to try to figure out how to intersect with the work of as many colleagues as possible.”

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections

This Byzantine reliquary from the thirteenth century, crafted of gold and cloisonné, was made to hold a fragment of wood from the cross on which Jesus was crucified.

Ziolkowski is only the seventh director in seven decades. (The appointment, which lasts for five years, is renewable.) Because directors are expected to spend one day a week in Cambridge, and to teach one class a semester, he is in a cab to the airport by 6 a.m. every Tuesday.

Over lunch in December, he confessed he was “running on vapors.” Although savoring his new role, he said, “I wasn’t prepared for just how active the place is.” Already that week, there had been a research report by a garden and landscape fellow on Monday afternoon; a concert on Monday night; a Byzantine seminar presentation by Papaioannou on Tuesday afternoon; coffee hour for the pre-Columbian fellows on Wednesday afternoon; and Mavroudi’s lecture on Wednesday evening. On Thursday evening, Ziolkowski was scheduled to give a talk himself on “The Juggler of Notre Dame,” a medieval folk tale about an entertainer who grows weary of his life, enters a monastery, and develops a juggling routine to perform before a statue of the Virgin because he doesn’t know how else to express his devotion. The tale—in which the juggler is scorned by his fellow monks-in-training, dies from the exertion of performing his routine, and ascends to heaven after a fight between the devils representing his tawdry past and the angels of his pious end—has found its way, in various forms, into nineteenth-century short-story collections, a W.H. Auden poem, and a short film narrated by Boris Karloff. A painting depicting the juggler, belonging to Ziolkowski, hangs in the director’s residence.

The estate owns that residence, a house across the street from the main campus that once belonged to Elizabeth Taylor. It has more bathrooms than Taylor has had husbands (nine and seven, respectively) and its extensive basement includes a film screening room, a minibar, and a children’s playroom decked out in zebra print. (There are also safes, which one would need if one planned on storing the 33-carat Krupp diamond and the 69-carat Taylor-Burton diamond.)

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks director Jan M. Ziolkowski

Ziolkowski hosted a dinner there for the fellows last fall, two days after he moved in. He thought it would be nice to do something casual, maybe pizza in the backyard. But tradition called for something grander, so Ziolkowski assented to a starched-tablecloth, waiters-in-tails affair, in keeping with the general ambiance of Dumbarton Oaks—teacups and tea are always in close proximity, and Pellegrino water and Amontillado sherry are served during the fellows’ Monday-afternoon research reports.

The estate also owns an apartment building 10 minutes from the campus, where the fellows live, and the campus includes a refectory where they can eat breakfast and lunch daily, on china that may have belonged to the Blisses, underneath a watchful portrait of Mrs. Bliss herself. “It was very important to the Blisses…that scholars be unencumbered by practical concerns,” says Joanne Pillsbury, director of the pre-Columbian studies program.

Their mission, broadly conceived, was “to bring together intellectuals,” Ziolkowski says. “Their focus was mainly on scholars, but they didn’t use that term to mean solely Ph.D.-bearing researchers. …They wanted them to come together in a context that would be beautiful, that would be aesthetically satisfying. They wanted people literally to step outside and smell the roses.”

In the nine decades since the Blisses first contemplated making their gift to Harvard, Dumbarton Oaks has gone from a building to a campus with a staff of close to 100. The Blisses’ endowment has enabled this to happen without any fundraising; their original $5-million gift had grown to nearly $500 million in 2001, the last time it was separately reported in University financial statements.

The Blisses had the foresight to realize they could not predict every eventuality, and they wrote the gift documents to give their estate’s future custodians discretion. This has allowed the institute to sell, over the years, all but the most precious holdings from the “house collection”—art the Blisses collected that fits into neither the Byzantine nor the pre-Columbian category—and plow the proceeds back into programs, publications, salaries, and library acquisitions.

The Dumbarton Oaks library, originally assembled to make sense of the Blisses’ collections and their gardens, has grown into a staple of scholarship for all three research fields. Their 10,000 volumes in Byzantine studies have grown to 150,000, plus half a million images of various sizes and formats. The pre-Columbian collection now numbers 32,000 volumes, up from the 2,000 collected by Robert Bliss. And the garden and landscape library, first curated by Mildred Bliss, grew from 5,000 volumes at the time of the Blisses’ conveyance to 27,000 today. The holdings of the library as a whole grow by 3,000 to 4,000 volumes a year.

Its home, a new building that opened in 2005, is a dramatic improvement: previously, books were kept in the main house, “literally shelved in closets and under stairs,” says library director Sheila Klos. “Every time the fire marshal came through, he said, ‘You shouldn’t have books here.’ We said, ‘Just a little longer.’ ... We were shelved on eight different levels, four of which had no elevator or book-lift access, so everything was carried.”

The library holds many rare and important resources, including the Princeton Index of Iconographic Art, one of only five copies of this card catalog in the world. Brandeis University anthropologist Charles Golden, a pre-Columbian fellow this year, says the library’s excavation reports have been particularly useful for his effort to understand why the Maya destroyed a royal palace after a sixth-century military defeat and rebuilt it, in different form, on the same site half a century later. The project requires “a shovelful-by-shovelful description of what came out of the ground and how it came out of the ground,” says Golden. “The only place to find that is the original excavation reports. Not all libraries are willing to buy them for the use of just a few scholars, but Dumbarton Oaks has them.”

And the fellows find that the library’s small size and ease of navigation make for productive research. “At Widener,” says Mavroudi, “you have to walk several minutes—sometimes half an hour!—within the building to go from one book to the next. If you are playing with an idea in your mind, maybe the idea is not the same by the time you reach the book. At Dumbarton Oaks, it’s just one floor up. It’s an immediate satisfaction of curiosity that allows one’s mind to work faster.”

While many are unaware of Dumbarton Oaks’ existence, even fewer know of the breadth of its offerings. Klos recalls a recent conversation with a book dealer who said, “Oh, Dumbarton Oaks, you do pre-Columbian.” Klos’s reply: “No, no, there’s so much more!”

To members of the general public, the estate’s name may be familiar in the context of international relations: late in World War II, representatives of the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and nationalist China gathered there to hammer out the details of the United Nations. Washington, D.C., residents may know the gardens (unlisted in many guidebooks), but even they often don’t realize that the museums are open to the public. (For visiting information, see www.doaks.org.)

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks

Curator and museum director Gudrun Bühl

Both Ziolkowski and museum director Gudrun Bühl are eager to increase the estate’s public profile. Bühl edited Dumbarton Oaks: The Collections, a 380-page book being published this spring under the Dumbarton Oaks imprint. With photographs of, and descriptive essays about, more than 170 objects from the Byzantine, pre-Columbian, and house collections, it is the first attempt to represent the holdings, in color, in all their breadth. (Among the smattering of previous books, some focused on the estate’s history, some on the gardens, some on one museum collection, often with images in black and white or no illustrations at all.)

A recent wave of renovations will also help. The new library building cost $18 million and comprises 43,000 square feet. The museums, closed for renovations since December 2005, were scheduled to reopen in April. And renovations to the Blisses’ former residence—which their sundry additions expanded to an awe-inspiring 77,000 square feet—were completed last year. (The building comprises offices for staff and fellows, rooms for concerts and lectures, the museum galleries and storage, the publications department, and a rare book room that was the only part of the library to stay behind after the new building’s construction. The holdings, all from the Blisses’ collection, include a first edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a signed copy of Leaves of Grass, and a fifteenth-century illustrated manual of medicinal plants.)

The new museum galleries—the first update since initial installation in the 1960s—attempt to integrate the collections and make them more user-friendly: for example, by adding new labels and educational display formats. One case holds a map of the Byzantine Empire, which serves to educate viewers but also to display Byzantine coins, arranged according to where they were minted.

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections

A pendant representing the crocodile god, one of the most widespread deities among the pre-Columbian peoples of what are now Costa Rica and Panama. Made of a gold and copper alloy, the pendant is believed to be between 500 and 1,300 years old.

The exhibits aim to be succinct, not exhaustive. “If you want the person to stop and look closer, then you have to cut back on the number of objects in one case,” says Bühl. But, she says, “It hurts. You want to show what you have.” Objects will rotate in and out of displays, while a new study space in the basement allows scholars to view objects from storage by appointment.

Bühl tries to use objects’ settings to suggest their original uses. “Most of these objects were never meant to be independent pieces of art,” she says. Floor mosaics, for example, were walked on—and so a mosaic from a Roman bathhouse floor adorns the museum’s entrance lobby, even though the constant foot traffic is a nightmare from a preservation standpoint.

But the displays stop short of wholesale reconstruction. One case contains early Byzantine liturgical instruments, including a reconstructed altar with a tabletop, chalices, a flabellum (a fan used during services to keep flies away from the communion host), and a liturgical book cover. It is significant, says Bühl, that this altar diorama appears inside a case, rather than in a full-scale reproduction of a chapel: “People should always know that these objects are lost to the original context.”

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections

This jade figurine from the Olmec culture, which flourished from about 1200 B.C. to 400 B.C. along the Gulf Coast of Mexico, was the first pre-Columbian object Robert Bliss acquired. It appears in an exhibit about the Blisses that was installed for the museums’ grand reopening in April.

The pre-Columbian collection resides in a distinctive honeycomb-shaped structure, designed by the architect Philip Johnson ’27, B.Arch. ’43, that was added as a wing of the main house in 1963. The holdings focus on Mexico and areas south. The post-renovation orientation of the displays is geographic, and each gallery also has a theme. One—featuring objects from the classic Veracruz culture, on the east coast of modern Mexico—informs viewers about the culture’s widespread ball games, believed to have served both ritualistic and recreational functions; the athletic equipment on display includes stone elbow and knee protectors. In another gallery, visitors learn about Maya religion by viewing a bust of the maize god and a bowl with a carved image of the chocolate god.

The Blisses snubbed the sensibilities of their time in favor of collecting pieces that brought them pleasure. Just as they were early Byzantine enthusiasts, Robert Bliss “was ahead of his time” in collecting pre-Columbian artifacts, says Bühl: his collection, first displayed at the National Gallery, was one of the earliest to recognize the objects’ artistic value, as well as their status as historical artifacts. A special exhibit for the grand reopening features his first acquisition, a nine-inch-tall jade Olmec statuette he found at an antique shop in Paris in 1912. Here, the figure assumes a double meaning, commenting on both Olmec culture and the Blisses’ life history.

The main house, which dates to 1801, is a museum in itself, exquisitely decorated with floors of exotic Hawaiian wood and furniture collected during the Blisses’ travels around the world. After buying the property, they added a greenhouse, a stable (which by the time they completed it was a garage instead), an orchid house (today a periodical room attached to the new library), servants’ quarters, the museum wings, and, of course, the gardens. But their main structural addition was the music room.

Photograph courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks

The Blisses spent just seven years at Dumbarton Oaks after Robert Bliss retired from the Foreign Service in 1933; they gave their estate to Harvard in 1940. This photograph shows them in 1938 in the music room, which they designed as a setting for chamber-music performances and spared no expense in decorating—the sixteenth-century mantelpiece of carved limestone came from a chateau in France’s Dordogne region. Today, the room is the setting for a monthly concert series presented in accordance with the Blisses’ wishes.

In decorating this room, they spared no expense. The appointments include a fireplace with a hulking sixteenth-century limestone mantelpiece that stretches to the 15-foot ceiling. Its previous home was the Château de Théobon, in the Dordogne. (The Blses had to have the foundations of the house reinforced beneath the spot where it would sit.) They also commissioned a multicolored, ornate ornamental ceiling as well, copied from a chateau in the Loire Valley. A monthly, public concert series fulfills their wish to have the room used for chamber-music performances.

On one December evening, the concert is by the vocal ensemble Pomerium. (Fittingly, its medieval Latin name translates as garden or orchard.) In the minutes before the concert begins, people crane their necks unabashedly to stare at the ceiling, recently restored to its original state after years of bad restorations that had, staff members ruefully recall, left cherubs looking like Casper the Friendly Ghost. Along the sides of the room are a work by El Greco; an early Renaissance painting depicting the martyrdom of Saint Peter, painted in the fifteenth century by Jacobello del Fiore; and a wooden sculpture of the Virgin holding the Christ Child, carved as a model for a life-size version by the fifteenth-century German sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider.

The ensemble sings in front of a Palladian arch; tapestries from the fifteenth century hang above the singers’ heads. The scene is framed by the floor of red Verona marble, the Italianate columns, the gilded bronze wall sconces—designed for candles but now electrified—and the massive silvered-brass light fixtures, said to be from the cathedral of Segovia in Spain.

The program is songs of Christmas, but not those that would be familiar to modern ears. The ensemble sings in Latin, starting with a monophonic Gregorian chant version of each song—haunting in its sparsity—followed by its layered and textured polyphonic elaboration, like a stove with all its burners going at once, different dishes bubbling and boiling. Some listeners are undoubtedly considering this a commentary on stylistic change between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance; others, just as certainly, are simply appreciating the lush sounds. The Blisses’ names may be unfamiliar to many listeners, but this scene fulfills their wishes just the same.

,

,