Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, who assumed the name Le Corbusier, became one of the world’s most influential, and controversial, modern architects and city planners. His legacy resonates at Harvard, because the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, on Quincy Street, is the only Le Corbusier-designed building in the United States. His work as a whole is newly accessible in Le Corbusier Le Grand, an enormous (20-plus pounds, 768-page, $200) catalog, archive, scrapbook, and assessment recently published by Phaidon.

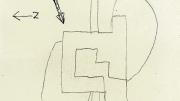

The Carpenter Center appears on pages 718 through 727, from Graduate School of Design dean Josep Lluis Sert’s 1958 letter soliciting Le Corbusier’s interest in the commission, through the minutiae of his contract, sketches, detailed drawings, the finished structure, and news coverage of its critical reception. In Harvard: An Architectural History (1985), Bainbridge Bunting wrote that the distinctive ramp “that curls up and through the [structure] with such showmanship can hardly be justified; it conducts visitors from one corner of the lot…through the building, and down to the opposite corner without allowing them to enter. The real entrance…is placed obscurely in the basement.…In the Cambridge climate surely little practical use can be made of the extensive roof gardens or the semi-subterranean loggias, which must have caused excessive complications in the framing.” Moreover, the center’s stark concrete exterior contrasts sharply with its red-brick neighbors, the Faculty Club and Fogg Art Museum, affronting traditional sensibilities.

Bunting got some things right: although the roof garden affords marvelous views, it is little used; an adjacent café and gallery had a sadly short life. And Bunting acknowledged that the “calisthenics of this design” produced a “geometry of solids and voids” whose liveliness makes ornamentation irrelevant: “the building itself is now sculpture.” It affords passersby an unusually deep view into the intriguing studios and workshops within, where art is made, and a changing panorama of exhibitions in the main gallery. (Would that Harvard’s new scientific laboratories were equally expressive.)

The activities Le Corbusier’s center supports will attract new attention this fall, as the University task force on the arts makes its report. Meanwhile, the neighboring Fogg complex will begin to cast off some of its familiar, traditional veneer as Renzo Piano’s renovation design is implemented during the next five years (see “Approaching the Arts Anew,” January-February, page 51, and “Open Access to Art,” July-August, page 58). Thus the conversations about architecture and its context provoked by Le Corbusier will be revitalized and extended, in University debates and in print, in the months ahead.

~J.S.R.