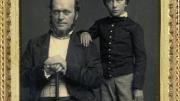

In the photograph, Henry James Jr., the future eminent novelist, is only 11 years old. He stands beside his seated father, Henry Sr., a somewhat portly, bearded man resting his hands atop a cane, an appurtenance necessitated by the wooden leg that replaced the one he lost in a fire as a boy. It is 1854, and the two Jameses are posed for a daguerreotype in the New York City studio of Mathew Brady, who several years later would make his place in history with powerful photographs of the Civil War.

In Brady’s placid father-son portrait, the younger James wears a military-looking jacket, its nine buttons fastened right up to the collar, and holds a wide-brimmed straw hat with a ribbon encircling the crown. The most telling detail, however, is the way the boy, who stood on a box for the picture, casually rests a forearm on his father’s shoulder. “It illustrates how people posing for portraits in the nineteenth century tried to convey their status, character, and modernity in pictures,” says Robin Kelsey, Loeb associate professor of the humanities. “The pose conveys the extent to which the elder James was a progressive and permissive parent—he grants his son an autonomy and authority that was quite unusual at the time. Most portraits of that era establish the father as the patriarch in no uncertain terms.”

Webb Chappell

Robin Kelsey

In his course Literature and Arts B-24, “Constructing Reality: Photography as Fact and Fiction,” Kelsey teases apart scores of photographic images to reveal what they imply. The course not only treats historic and artistic photographs, but also ranges through medical and forensic photography, “spirit photographs,” the photography of social reform, advertising, politics, war, law, and criminality, plus family albums, calendars, and coffee-table books. Kelsey views photography as a “hybrid medium” that is both a simple, automatic trace of reality and an intentional composition that fits the Western pictorial tradition: rectangularity, a single viewpoint, perspective, a vanishing point. “You can sit and spend time with a single photograph in a way that I find very gratifying,” he says. “For me, the images reveal themselves only through long and repeated viewings.”

With few exceptions, scholars of art history were slow to investigate photography; instead, those in disciplines like American studies and English did the pioneering research. Recently, trained art historians like Kelsey have become deeply engaged, but it remains a small field: “We all know one another and each other’s work,” he says. (He and Blake Stimson, professor of art history at the University of California, Davis, edited The Meaning of Photography, which appeared this past year.) The study of photography is growing—part of a larger trend toward the study of visual material in general—though it must compete for resources at a time when many art-history departments are working to become less Eurocentric and to strengthen their African, Asian, and Latin American sub-fields, for example.

The similarities between what Kelsey does with photographs and what art historians do with paintings are greatest with consciously artistic photographs, such as those of Alfred Steiglitz. Yet there are differences. “In the study of painting, one can assume, generally speaking, a high degree of intentionality behind the particulars of the work. Van Gogh used his brush just so, because he wanted the painting to look just like that,” Kelsey says. “With photography, especially the instantaneous photographs using fast shutter speeds that became the norm in the twentieth century, chance plays a much larger role in creating the image.” (Indeed, Kelsey’s next book, due this year, is titled Photography and Chance.) “Chance undercuts your authority over the image,” Kelsey notes. “One of the struggles for photographers in the twentieth century was how to rationalize chance out of the image.”

For example, Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose astonishing street photography revolutionized the art, argued that he could compose a picture in a fraction of a second. His 1952 book, Images à la Sauvette (“images on the run,” or “stolen images”), whose English title is The Decisive Moment, epitomized this style and coined an entry for the photographic lexicon. At the other extreme, contemporary photographers like Gregory Crewdson and Jeff Wall create elaborately staged and painstakingly produced photographs that have been called “one-frame cinematic productions”—ratcheting up the authorial element by controlling every facet of the composition.

Though Cartier-Bresson’s instantaneous slices of life might seem to argue otherwise, Kelsey cautions that one of the dangers of interpreting photography is that “Images are taken as unproblematic reflections of reality. The object of my course is to prepare students to think more critically about the images they encounter, to be more sophisticated in their understanding of how images work, and to ask why one image, and not another, gets used.”

Take, for example, those melancholy Civil War photographs that depict a battlefield with a soldier’s corpse in the foreground, his rifle on the ground beside him. “Any viewer in the late 1860s would have realized that no one would have left a rifle on a battlefield,” says Kelsey. “Those corpses were looted for their boots, for money—and rifles were very scarce. Yet viewers weren’t upset; in the nineteenth century, people seemed much less concerned with the ways in which photographs were at times staged. By the 1930s, when allegations arose that a New Deal photographer had inserted the skull of a steer into photographs of parched agricultural land to accentuate the sense of suffering, people were very disturbed. It had to do, in part, with the rise of journalism as a modern institution and a new ethical code that accompanied this.”

Repeatedly, Kelsey returns to the status of photographs as evidence—in convicting criminals, selling products, diagnosing diseases, or documenting atrocities. “Evidence was one of my favorite courses in law school,” says the scholar, who interrupted his Harvard doctoral program in art history to attend Yale Law School and practice for two years in San Francisco. (He completed his Ph.D. in 2000, and joined the faculty in 2001.) “I very much like photography because its aesthetic values are always mingling with its evidentiary values. After more than 150 years, we are still confused by that. Our understanding of photographs as evidence cloaks their function as pictures—we tend to forget all the conventions and choices that go into the production of a photograph because it still seems a simple, direct trace of the world.”

In the early years of photography, amid the Industrial Revolution, “People were very concerned about the fallibility of human vision,” Kelsey explains. “In a conflict between a photograph and the human eye, the machine was thought to be superior.” In the 1880s, “fast” (more light-sensitive) emulsions and high-speed shutters appeared. “Suddenly, people could see images of bodies frozen in motion, and it was startling,” he says. “Artists had represented people running or horses galloping in accord with certain conventions of grace and beauty. Now photographs were showing bodies in motion in a very different way, and many people found these images shocking and awkward-looking. The frozen image is not available to everyday experience. The authority of photography was such that people believed the photographs had gotten to a deeper reality.” (Today, in a world in which the “snapshot aesthetic” has long since become the norm, a Sports Illustrated shot of a base runner splayed across home plate has become visually pleasing.)

By the late nineteenth century, photographs were also displacing and supplementing medical illustration. “Doctors might seek out and emphasize symptoms that showed up well in photographs,” Kelsey says. “In France, [neurologist Jean-Martin] Charcot used photographs extensively in his studies of hysteria. It seems clear that he interpreted hysteria in a way that made the photographs as significant as possible, emphasizing these theatrical gestures the patients made. You could analyze hysteria in terms of the utterances and sounds patients made, but Charcot stressed the visual cues.”

The advent of the Kodak camera in the late nineteenth century put photography in the hands of many more (and less serious) amateurs and vastly increased the number of images captured on film. (In 1888, George Eastman made up and trademarked the name “Kodak” and soon coined the slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest.” At first, customers returned the entire camera, with 100 exposed film images, to Kodak for processing.)

In earlier decades, nearly all portraits were formal studio shots, but “snapshots” enabled “candid” pictures. “The idea that people reveal more of themselves to the camera when they are unaware of it is more than a century old,” Kelsey says. “But what we call the ‘candid’ photograph in our photo album is hardly a typical picture of the subject. What we put in our photo albums are idealizations. The obligation to smile for the camera is a way of ensuring that we always look like we are enjoying ourselves at birthday parties or on holidays and vacations. Even if we are miserable, the photo album will insist that we are having a great time.”

Idealized self-images are buried deep in the psyche. Kelsey points to a recent study showing that when a digitally idealized image of ourselves appears in an array of images, we pick ourselves out faster than we do with an unimproved image—yet we locate friends and acquaintances more quickly from unimproved images.

The practice of improving, enhancing, distorting, and otherwise manipulating photographic images with computer software—as with previous techniques to doctor photographs—has led some to predict that viewers will no longer take photographs seriously as evidence. So far, that has not happened. The torture pictures from the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, for example, were widely credited as evidence of wrongdoing. “The Abu Ghraib pictures were not produced by photojournalists,” Kelsey explains. “Their credibility had to do with the fact that they are self-incriminating. It’s hard to believe that someone on the inside of the prison would have doctored those photographs. The whistle-blower story was very compelling.

“Historically, what has sustained photographs as evidence is not simply the automatic nature of the medium, but journalistic codes of integrity,” he continues. “After all, when writing a verbal report of an event, one can make up everything, but we do still take what we read in newspapers seriously, due to our faith in the integrity of the institution. Now photography will have to rely on those forms of trust, rather than on simple faith in the technology itself.”

Even so, in our media environment, the image often trumps the word—or even the deed. The “photo op” was “an invention of the Reagan presidency,” says Kelsey. “Ronald Reagan, who was an old movie actor, understood the importance of the camera in a way that no previous president did.” On the eve of the 1984 election, for example, CBS aired a hard-hitting piece by correspondent Lesley Stahl that criticized Reagan for cutting funding for the disabled and elderly, even while appearing in photo ops at the Handicapped Olympics and at the opening of an old-age home. To her surprise, as Stahl recounted in her memoir, Reporting Live, she received a call from Reagan aide Richard Darman ’64, M.B.A. ’67, complimenting her on the piece and praising its strong visuals. “They didn’t hear you,” Darman said. “They only saw the pictures.”

Today, of course, cell phones and the Internet have made nearly everyone a potential photojournalist. For Kelsey, the ability to disseminate images globally via the Web is a far more significant historical shift than the change from film to digital photography (though they are, of course, technologically related). “If we were just making digital pictures and printing them out, that would have a much less profound impact than what we have with the Internet,” he says. As an example, he cites images of 2007 street conflicts in Cameroon, transmitted daily by ordinary citizens with cell-phone cameras, who “could operate in a sense as photojournalists for people around the world.”

Furthermore, even as digital photography has made it easier to manipulate images, “the spread of photographic technology has made it easier to catch such manipulations,” Kelsey states. “In this moment of security videos and ubiquitous cell-phone cameras, anyone who fakes an image of a public event risks being exposed by what was recorded by another camera.” Consider an image released in July 2008 by the media arm of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. It shows four Iranian missiles successfully launching skyward, and was disseminated worldwide through major newspaper, television, and online outlets. Yet Agence France-Presse, which first distributed the picture, soon retracted it, explaining that it had apparently been digitally altered. (The Associated Press received a very similar image from the same source that showed only three missiles taking off.) The Iranian agency seemed to have added a fictional, fourth sky-bound missile to disguise the failure of an actual fourth missile. “Now that we have these conflicting images,” says Kelsey, “the question becomes: what is the most persuasive explanation for the incompatible pictures, what is the most compelling story we can tell?”

Telling stories with images has become central to modern life—economic, social, political, cultural. “The terrorists have certainly fought with images,” says Kelsey. “Though we must never diminish the value of the thousands who lost their lives in the World Trade Center attacks, it is also true that the effect of those attacks on this country as an image—the planes hitting and the towers going down—was psychologically devastating. The invisibility of the terrorists makes it difficult to respond with an equally powerful picture. The primary lesson: never underestimate the power of images.”