At a school in Peñalolén, a working-class neighborhood in Santiago, Chile, kindergarten teacher Patricia Pérez is reading to her class. The story involves a pig who wants to impress a lady friend so she’ll agree to go on a picnic with him. From a fox, a zebra, and a lion, he borrows items to spiff himself up: a tail, stripes, and a mane. When Mr. Pig arrives at his intended’s house, she doesn’t recognize him and refuses to go with him; he saves the day by coming back unadorned, prompting the lady pig to exclaim with delight: “¡Qué romántico!”

When the story ends, Pérez works with her pupils on vocabulary words such as consejo (“advice”—which Mr. Pig got from his friends, but should not have heeded), asking students to sound them out and write them on the board. In a nearby classroom, different kindergartners listen to their teacher reading; others read on their own, choosing from books strewn across tabletops.

Aldo Benincasa

Catherine Snow

To American visitors, these are unremarkable kindergarten scenes. In Chile, however, such scenes are less ordinary. Chilean children typically do not learn to read, or even begin working with the full alphabet, until first grade. “Early-childhood education has not, in Latin America in general, been thought of as education,” says Graham professor of education Catherine Snow. “The approach is: Let the kids play, get them used to being in groups, and we’ll worry about teaching them starting in first grade. But then in first grade, the expectations for progress are suddenly very high, and none of the preparatory work has been done. Kids kind of get dropped into the deep end.”

The hands-on approach to books in the Peñalolén classrooms is part of Un Buen Comienzo (UBC; “a good start”), a program designed with guidance from Snow and Harvard colleagues. It aims to improve the quality of early-childhood education in Santiago, increasing literacy and school success for the young participants. UBC is a project of the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE); a Chilean philanthropic foundation is underwriting and implementing it, and researchers from a Chilean university will evaluate its effectiveness.

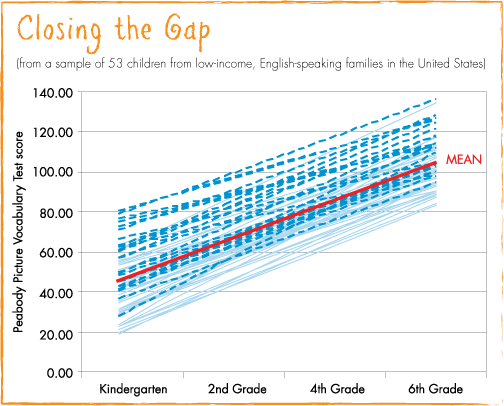

Un Buen Comienzo reflects a recognition of early childhood as a crucial time for the development, both emotional and cognitive, that influences children’s later lives. Chile’s expansion of preschool programs, integrated into the existing school system, offered a unique opportunity to reach children at a younger age. Past efforts tended to focus on later childhood, but “the cost-benefit ratio is more favorable in early childhood than at any point in the life cycle,” says HGSE dean Kathleen McCartney. In the case of some skills and abilities, in fact, by the time a child enters school it’s too late to have maximum impact. Children’s vocabulary at age five very reliably predicts the number of words they know in sixth grade (see chart below). “We know from a number of studies that a very good predictor of success in literacy is oral language skills,” says Snow. “So if kids are limited in the oral language skills that enable them to understand a story that’s read aloud, or to tell a story about an event in their own lives, then they will have difficulty accessing meaning in the texts they learn how to read in the first grade.”

Snow et al., 2007. Is literacy enough? Pathways to academic success for adolescents. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Each line in the graph above follows a child’s vocabulary growth from kindergarten through sixth grade. Note that the lines do not cross—the children with the largest vocabularies in kindergarten still had the largest vocabularies six years later. This is why it is crucial that preschool programs focus on building vocabulary and making up for the deficit that children in low-income families already face, says Graham professor of education Catherine Snow.

Because UBC incorporates rigorous evaluation of the strategies on trial, “I think countries across the world will be interested in the findings from this project,” says McCartney. “Most times, government education policy is driven by opinion, rather than data—by people’s best guesses about what will work.”

This dual approach—implementation and evaluation—is characteristic of Harvard’s aim to play a much larger role in improving the lot of children, in the United States and the world, through the interdisciplinary Center on the Developing Child (CDC; www.developingchild.harvard.edu), founded in 2006 with the goal of “advancing the scientific foundations of health, learning, and community well-being.” The center funds research by faculty and students and helps them take their findings out into the world—into the classroom, but also to the state and national capitols where policies are made. Even where a solid knowledge base exists, says CDC director and Richmond professor of child health and development Jack Shonkoff, “we don’t take it as a given that science speaks for itself in the policy world.” These efforts are already paying off for children, in Chile and elsewhere.

Teaching the Whole Child

Harvard has long had eminent faculty in child development —prominently including Julius Richmond, the late Harvard Medical School professor who served as founding director of Head Start and later as U.S. surgeon general (and who advocated for the CDC’s creation). But the University lacked a place where these researchers could combine efforts and share what was happening in their labs. President Neil Rudenstine created the Harvard Project on Schooling and Children in the early 1990s (see “Promoting a National Love of Children,” November-December 1996, page 52). But when Steven Hyman became provost in 2001, those leading the initiative recommended that it disband, Hyman recalls: “It was a volunteer, part-time effort—it wasn’t structured or funded in a way that it could be anybody’s full-time job. It was a labor of love tacked onto the day job of busy people, and that just wasn’t sustainable.”

Tired of waiting for a more effective umbrella organization, McCartney, Snow, and colleagues had begun work on UBC before Shonkoff arrived at Harvard and the center’s creation was announced. Now it is a flagship project in the center’s emerging global portfolio, reflecting the University’s fundamental interest in making a tangible difference in the lives of children. Snow is on the center’s steering committee. HGSE professor Hirokazu Yoshikawa, who is overseeing evaluation of UBC, is involved with multiple center initiatives. And UBC director Andrea Rolla, Ed.D. ’06, is a scholar in residence at the center this year.

Photograph by Aldo Benincasa

Andrea Rolla (third from left) and Hirokazu Yoshikawa visit a UBC school in Peñalolén.

And the interdisciplinary nature of the Santiago effort epitomizes the center’s approach. UBC combines professional development for teachers with workshops for parents, literacy with health, lesson content with a concern for classroom design. Says Rolla, “Children’s problems are interdisciplinary.” Training sessions prompt teachers to update their instructional methods to reflect current knowledge about how children learn: introduce reading through familiar words (instead of phonetic exercises that ask children to spell independently of context) and teach new vocabulary through stories instead of memorization. To expose children to as many letters and words as possible, hang posters and signs all over the classroom, label classroom objects, keep books accessible instead of hidden away in a cupboard, and post the letters of the alphabet at child’s-eye level, instead of near the ceiling.

For both teachers and parents, there is an emphasis on using “sophisticated vocabulary”—defined as anything beyond the 3,000 most commonly used words in the language. (Instead of saying “Eat your peas,” a parent might say, “You need to eat your peas because they have vitamins in them,” introducing an unfamiliar word in context.) The training also encourages the adults to be more verbal at every opportunity: if a child asks, “How do I tie my shoes?” the parent should talk through the steps—“first you make a loop. Then, you wrap the other lace around…”—instead of merely demonstrating.

The program’s designers quickly realized that making sure children learn means making sure they attend school consistently. In Santiago, where the Andes trap smog over the city and the air quality in winter is abysmal, children often get respiratory infections and parents may keep them home for weeks on end. In low-income comunas (districts of Santiago), winter attendance rates in preschool classrooms commonly drop to 50 percent or lower. (The average absence rate in the pre-UBC classrooms was more than 25 percent.) UBC teaches that children should attend school if at all possible (and donated hand-sanitizer dispensers hang in each classroom).

Parental engagement doesn’t happen automatically. In Latin America—and particularly in poor communities where parents lack advanced education—“families traditionally do not get involved in their children’s education,” says Rolla, the child of Argentine émigrés who grew up in Massachusetts, attended Princeton, and is married to a Chilean. At the entrance of each school, she says, “there’s a fence”—literal enough, but with symbolic value, too. “Parents drop their children o and pick them up.” Parents have told Rolla that before UBC, they thought that they were responsible for their children’s basic needs, but that education was solely the job of teachers. In a survey of UBC parents, 52 percent reported having 10 or fewer books at home. One quarter reported never reading to their children; another quarter reported reading to their children just once or twice a month.

After a pilot year, UBC’s second year has just concluded. The evaluation team is now measuring whether the program met its goals of enlarging students’ vocabulary, reducing respiratory infections, increasing school attendance, and getting all children to have annual physicals. It is examining children’s language use in journals and watching videotapes from the classrooms (professional development isn’t worth much if the teachers don’t use the new methods, Rolla notes). Says Yoshikawa, “We think that, with rigorous evaluation, you have a chance of influencing policy not just in Chile, but throughout South America—in fact, in middle-income countries everywhere.”

The program is focusing on poorer neighborhoods, at least to start, aiming to compensate for what is presumed to be a vocabulary-poor environment at home. At a cost of 45,000 Chilean pesos (about $75) per child per year, UBC is reaching 500 children already, and another 500 through less intensive intervention (see below). It will expand beyond Peñalolén to two other comunas this year, and by 2010 should reach almost 10,000 Chilean children.

Although the program is locally supported and run—critical elements for its credibility—there are frequent visits between Cambridge and Santiago. During an October trip to Chile, Snow, Yoshikawa, and MaryCatherine Arbour, M.D. ’05 (a clinical fellow in medicine at the Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital who is overseeing the health portion of UBC), visited one school in which the full program was being implemented, and one control school, which received five donated books per classroom (as opposed to 70 books for two or three classrooms to share with the full program), and self-care workshops to help the teachers avoid burnout.

At the first school, words and letters were everywhere. A single classroom contained a bulletin board with vocabulary words; the alphabet; a poster with days of the week; and posters of colors bearing their names. Outside the classroom hung drawings the children made, each one a scene from a book they read. On the door hung a poster listing the normas y reglas de la sala (the rules of the classroom) in the children’s own handwriting, not the teacher’s. Each element reflected the teachers’ new training. Above the school’s entrance gate hung a banner with a UBC-inspired message: Niño o Niña que no Asiste a Clases no Aprende (“Boys and girls don’t learn if they don’t go to school”).

When the program leaders met with teachers, one expressed amazement that her students were capable of the work the program assigns; she hadn’t believed it until she’d seen it. Another said, “Before, we would work on vocabulary words and then forget about them. Now, I hear the kids use them in conversation.”

At the second school, classroom walls displayed little written material. Books were nowhere to be seen, and certainly nowhere the children could access them easily. The pupils were gluing yarn to irregular shapes on paper, working on eye-hand coordination. There’s nothing wrong with this kind of exercise, Rolla explained, but it falls well short of engaging the full abilities of four- and five-year-olds. Absent language and literacy activities, the children miss opportunities for more rapid development.

How Stress Becomes Biology

Beyond bringing Harvard’s scholarship to bear on programs for children, the Center on the Developing Child’s brief also includes creating new knowledge. CDC director Jack Shonkoff explains that the center aims “to build a very strong science core that focuses on increasing our understanding of the underlying science of disparities”—of the factors that contribute to healthy development for some children and less good outcomes for others.

A center-funded study on the biology of early adversity will use recent advances in genetics and molecular biology to learn more about how stressors such as child abuse and neglect, or just growing up poor, affect physical and mental health across the lifespan. The researchers, six professors from three different Harvard faculties conducting human and animal research, are studying biomarkers, including telomere length and oxidative stress.

The telomere is a region found at both ends of every chromosome in cells throughout the body. Each time DNA replicates, the telomere shortens slightly: older people have a shorter average telomere length than younger people. This shrinkage is thought to be a natural part of aging—and perhaps even a physiological cause of the debility and disease that accompany it.

Intriguingly, recent studies have found a link between stress and accelerated telomere shortening—one documented especially short telomeres among adult caregivers for children with chronic problems such as autism. “By one estimate, they had lost 10 years of life through the chronic stress of taking care of these kids,” says professor of pediatrics Charles A. Nelson III, who holds the Scott chair in pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Boston and is one of the principal investigators.

Oxidative stress—also implicated in aging, and measured through a molecule in the blood—is the process by which free radicals, byproducts of the body’s use of oxygen, damage cell components including DNA. A diet of foods high in antioxidants (which neutralize free radicals) bolsters the body’s own antioxidant production; lifestyle factors such as smoking, exposure to pollution, and stress may overwhelm these natural defenses to bring about disease.

Nelson, who is also a member of the faculties of education and public health, is studying telomere length and oxidative stress in a population he knows well: Romanian orphans raised in institutions under heartbreaking conditions. Infants, for example, were left in cribs all day, except when being changed or fed. “No one responds to them if they cry, and as a result, no one cries,” he says. “The weirdest thing when you walk into this room for the first time is how quiet it is. There’s no talking, there’s no crying, there’s nothing.” Older children showed severely stunted growth and indiscriminate friendliness, sitting in the laps of complete strangers or happily walking off with them.

Michael Carroll

Children in Romanian orphanages are raised in conditions of social and cognitive deprivation. In many cases they receive no adult attention other than being fed and taken to the toilet as a group a few times a day.

Charles Nelson

This 11-year-old girl, raised in an orphanage in Romania, was only as tall as an average four-year-old child when the photograph was taken.

Charles Nelson

In these brain “heat maps”—seen from above, with the triangles at the top indicating the front of the head—red corresponds to high activity and blue connotes no activity. The different frequency bands (left-hand scale) reflect different types of brain activity, but across all frequencies, the level of activity was lower for children raised in Romanian orphanages (left column) than for those who grew up with their parents (right column).To explain these disturbing observations, Nelson in 2000 began an exhaustive study of a cohort of children born that year and abandoned to orphanages, compared to a control group of children living with their families in Bucharest. He found a much higher incidence of mental illness among the children who grew up in the social and cognitive deprivation of the orphanage, as well as major differences in brain activity (see chart at left) and IQ. Half the orphans were placed in foster care, while the other half remained institutionalized; Nelson found that those placed in foster care before the age of two recovered about half of the IQ deficit, but orphans placed later had IQ scores nearly identical to those of children who stayed in the orphanage. He concluded that the first two years of life are crucial for normal development of language, cognition, and mental health—diverse faculties that develop apace in a normal family environment, but not in an institution with minimal interaction. These findings have already led to action: in 2003, in response to his work, the Romanian government passed a law forbidding the institutionalization of any child younger than two unless the child is severely handicapped.

In the current study, Nelson will examine the biological toll of early adversity by testing whether institutionalized children have shorter telomeres and more evidence of oxidative stress than children raised with their families. Colleagues will examine the same dimensions in two American samples—a large national longitudinal study and a group of youths with posttraumatic stress disorder—in hopes of quantifying the relationships among early adversity, elevated oxidative stress and shortened telomeres, and poor emotional, physical, and cognitive outcomes. The overarching goal is to get a better idea of how stress becomes biologically embedded, and precisely when intervention is most effective.

Takao Hensch

Takao Hensch (professor of molecular and cellular biology and of neurology) uses a contrast test to assess vision in mice. Mice that receive no visual input (for instance, because they are blindfolded) during a critical period will almost certainly be permanently blind—but Hensch has found a way around this. Using drugs approved for other uses in humans, he has induced plasticity in the visual system later in life, making blind mice see (and, conversely, making seeing mice blind by removing visual input after administering the drugs).

It is well established that in humans, critical periods exist for vision and some components of language (most notably, acquiring the syntax of a first language). Such sensitive periods in brain development are the specialty of Takao Hensch, professor of molecular and cellular biology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and professor of neurology at the Medical School (HMS). Building on the work of David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel (the Nobel Prize-winning HMS researchers who demonstrated the concept of critical periods for brain development by studying vision in cats), Hensch has identified the cell type that controls brain plasticity for the visual system. “Plasticity” refers to the capability of the brain to adapt its structure in response to experience; some parts of the brain remain malleable through adulthood. The visual system, on the other hand, is “wired” early in life, and then plasticity ends. Humans and animals that receive no visual input during the critical period (say, because they are blindfolded) typically are permanently blind, but recently, Hensch has induced plasticity in adult mice using drugs already approved for other uses in humans.

Much work remains to be done on whether plasticity could be induced in humans. But in the CDC study, Hensch and assistant professor of neurology Michela Fagiolini are investigating whether such complex and varied phenomena as autism and schizophrenia might also be critical-period disorders. Their hypothesis is that stress can cause abnormalities in basic brain systems and processes—specifically, in the formation of the myelin coating that allows neurons to transmit electrical impulses, and in the functioning of GABA, the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain.

Autism, says Hensch, “smacks of a critical period gone awry. It’s identified around three years after birth. Parents report that their children were normal up to that age, and then suddenly they’ve gone o track.” The search for genes involved in the disorder has led to many different candidates. The fact that such different genetic signatures manifest themselves the same way—“there’s an imbalance between excitation and inhibition,” in Hensch’s words—has led him and others to wonder whether autism stems not from the DNA, but from something about the way genes are expressed and the brain architecture is laid down. “Maybe different parts of the brain are becoming plastic either too fast or too slow,” he says. “We know that different brain regions feed into other brain regions, and so either degraded or accelerated maturation will cause the next stage to develop better or worse.” (For more on Harvard scientists’ research on autism, see “A Spectrum of Disorders,” January-February 2008, page 27.)

Hensch notes that scientists in Scotland have induced Rett syndrome, an autism-spectrum disorder, in mice by removing a single gene, and have also engineered mice in which the gene was dormant early, but could be switched on during adulthood—at which point, the second set of mice became normal. “This was tremendous,” says Hensch. “It suggests that this one mutation could produce something as severe as Rett syndrome, and yet all of brain development is lying dormant and could be rekindled.”

Meanwhile, research by associate professor of psychiatry Martin Teicher suggests that sexual abuse affects children differently depending on the age at which it happens. And Nelson’s research points to critical periods for other cognitive and emotional faculties. In addition, Nelson is running a study of autism risk in infants whose older siblings have the disease. Convergences like these explain the scientists’ excitement at working together. “I think we’ll find that many of the psychiatric disorders in humans will have a critical-period origin,” says Hensch, “that an early insult around birth or a genetic defect…will predispose brains to wire incorrectly.”

Practicing Good Policy

Translating scientific advancements into policy requires creating programs that incorporate cutting-edge science—and then testing those programs to see if they work. But such translational efforts have lagged behind. In reality, most contemporary proposals for early-childhood education depend on four fundamental studies begun decades ago: the Perry Preschool Study, begun in Ypsilanti, Michigan, in the 1960s; the Abecedarian Project, undertaken in North Carolina in the 1970s; the Brookline Early Education Project, begun in Massachusetts in the 1970s; and the Chicago Child Parent Centers launched in the 1980s. These studies “are still the foundation for government investment in preschool education all over the world,” says Hiro Yoshikawa of HGSE. “There’s a great need for conducting these kinds of rigorous evaluations on early-childhood education now.”

To that end, he is working on a program the Center on the Developing Child is launching in Tulsa. Although its context is utterly different from the program in Chile, the questions asked and concerns considered in program design are similar. Tulsa was chosen not only because it has “some of the worst health statistics in the nation,” according to Jack Shonkoff, but because of willing partners: the University of Oklahoma School of Community Medicine, the George Kaiser Family Foundation, and Tulsa’s Educare Center.

Involving faculty members from Harvard’s schools of education, medicine, and public health, this project envisions going even further than UBC in addressing multiple facets of a child’s life. Besides school readiness and health, the initiative will wrap in workforce development (job training and placement for parents) and behavioral economics (from explaining why check-cashing and payday-loan services that charge steep fees are a bad deal, to trying to pass laws that ban predatory financial practices).

Of the nascent project, Shonkoff says, “What’s distinctive about it is that it truly integrates cutting-edge thinking in early literacy, child and parent mental health, and economic security for low-income families.” These aims mirror his own Harvard appointments, in the schools of education, public health, and medicine. The Tulsa team reflects that range of skills, too. Among the participants are Richard Frank, Morris professor of healthcare policy, who specializes in healthcare finance and, in particular, in evaluating claims that specific policy changes will generate enough cost savings to pay for themselves; Bill Beardslee, Gardner-Monks professor of child psychiatry, who has examined how to protect children from the harmful effects of parental depression; Catherine Snow; and Yoshikawa, who has coedited a book on improving outcomes for children of low-wage workers.

From such innovative programs and watertight evaluation will come new knowledge about how best to help children. If this knowledge reaches a wide, influential audience, Shonkoff hopes the tide will turn in the direction of supporting early-childhood programs across the United States—programs that he says are “grossly underfunded.” Nearly 45 years after its founding, Head Start “is serving half of the kids it is meant to serve”: about one million American four- and five-year-olds were enrolled in 2006, but nearly two million live in families poor enough to meet the income guidelines. (The program costs $7 billion a year; to serve all eligible children, the government would need to double that amount.)

Early Head Start is in even worse straits. That program (which costs $11,000 per child) reaches just 96,000 children age three and younger—less than 3 percent of those who qualify. “With a few exceptions, every developed country in the world has a better system of publicly supported early care and education than the United States has,” Shonkoff says. “The concept of shared responsibility for each other’s children is not part of our political culture.”

Questions about these programs’ effectiveness also hold up efforts to allocate more funding. “There is tremendous variability in the quality of the implementation of Head Start,” he acknowledges. The challenge is to identify the features that successful providers share, to get more providers to incorporate those practices—and to develop new approaches with even greater impact.

Another challenge: convincing politicians and the public that “early childhood development is economic development,” in the words of Arthur Rolnick, who spoke last year at a CDC colloquium at the Business School. Rolnick is senior vice president and director of research for the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, which is helping coordinate an experimental preschool program in St. Paul. The most successful preschool programs provide a large return on public money, Rolnick noted: for instance, evaluations have shown the Perry Preschool program returned $17 on each dollar invested. And the biggest return, he said, is savings associated with crime (not just on prison budgets, but also on judicial and law-enforcement expenses, and costs to communities to repair damage from criminal acts). This type of investment equips the next generation to succeed in school, to graduate instead of dropping out, and to find jobs.

What’s more, says Provost Hyman, the stakes are huge for keeping the United States competitive. Providing children with supportive environments and making sure they have what they need to succeed in school, he says, are tasks “central to the success of our society.”