The art opening on July 1 had the usual ingredients: about four dozen works on display, refreshments, social mingling, and the painter circulating throughout the room. But the location—the ARKA Gallery in Vladivostok, Russia, on the Sea of Japan in eastern Siberia—made it an historic occasion: the first-ever exhibit of its kind of works by an American artist in the Russian Far East. The U.S. consulate and Vladivostok city administration co-sponsored the event as part of celebrations of the city’s sesquicentennial.

The voyage to Vladivostok demanded some tricky packing by that artist, George Oommen, M.A.U. ’70 (www.goommen.com). Though he lives in Boston, where he worked from 1970 until 2007 as a senior project manager for Harvard Planning and Real Estate, Oommen was born in Kerala, in southwest India, where the summer temperature easily reaches 111 degrees Fahrenheit. He stopped there on his way to Siberia, with its 48-degree weather; before the big opening, it was worth reconnecting both with family members and with the source of his inspiration.

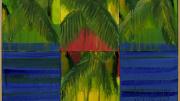

Each December, Oommen returns to Kerala for three or four months to “recharge my batteries” he says, and to soak up the tropical imagery that dominates his paintings, which exude an “extravagantly charged vitality reminiscent of the sensual worlds of Henri Matisse,” wrote Art in America critic Dominique Nahas. “The glorious colors of the harvest season,” Oommen recalls, savoring a memory of Kerala, “and fields of growing rice, and thatched huts.” He likes an inland island, Mankotta—“few know about it”—that is only 20 miles from his Kerala home. There he goes out early in the morning, when the sun has barely risen. The still water becomes a mirror, “and you see everything double. The only other place I have seen like that is Lake Como in Italy.”

Oommen doesn’t take his easel outdoors, however. “I always paint from memory,” he explains. “If you can’t remember it, it’s not worth painting.”

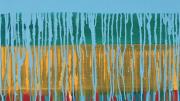

He creates his abstract landscapes mostly in acrylic and oil paints and, since 1994, has often used a drip technique in which he squirts water (or turpentine, for oil-based paint) at the top edge of the canvas and lets it trickle down, taking paint with it and creating a vertical line on the surface. “I use water to paint water,” he explains. Generally, he fills the frame with many parallel drips that, depending on the subject, can suggest raindrops on a window, wooden blinds, hanging vegetation, tree trunks, or the fabric of silk saris. His technique differs from the drippings of “action painter” Jackson Pollock, whose work “doesn’t speak to me,” Oommen says.

Instead, he cites the influence of the celebrated British artist Sir Howard Hodgkins, who “paints feelings. That’s very tough to do,” says Oommen. “I tried to see if I could paint my feelings. I went back to the things I remember most—my first girlfriend, first kiss, first love. You start with a feeling, and when the feeling comes back to you by looking at the painting, the painting is finished.”

All the paintings in the Vladivostok show are two feet square; he has recently experimented with printing some pictures on metal sheets, using a giclée process—making ink-jet prints from a digital source—and mounting them with magnets. He can even print different works on both sides of the metal. Images on metal might, in the future, prove an economical way to ship and display art, he notes: just to pack, ship, insure, and shepherd his paintings through customs to Vladivostok cost $10,000.

Oommen says he spends half his time lately on the business end of art. (His works typically sell for $3,000 to $4,000.) He is used to budgets. Trained in both architecture and urban design, he supervised much of the construction across the Harvard campus in the past few decades (“from fundraising to ribbon cutting”), including the Murr Center, the Bright Hockey Center, and the Tanner Fountain, with all its boulders, in front of the Science Center.

As a young architecture student in India, he once met Le Corbusier, who designed much of the city of Chandigarh, and the great architect remarked, “You’re a student? You should always be a student.” And, Oommen says, “I’ve always been a student after that. It’s kept me young, kept me open to new techniques.” Indeed, for 20 years he has studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where a fellow student once suggested a way to stop his drips from running off the bottom edge of the canvas: “Have you tried shaving cream? It absorbs all the color and then it evaporates.” Oommen has used the method ever since: “At the school, I’m known as the guy with shaving cream and a beard.”