The Kenyan dwarf gecko was what first drew Harvard research fellow Robert M. Pringle to the savannas of Kenya, but the termites kept him there. After he and his co-workers noticed large spikes in these lizard populations surrounding termite mounds, they decided to quantify just how much the mounds enhanced ecosystem productivity.

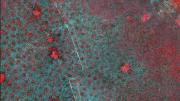

The presence of termites was already known to increase the number of plant and animal species that a given area could support (largely because they recycle dead organic matter). What startled Pringle was the view from above the savanna. Having noticed that the mounds seemed fairly evenly spaced, he obtained a satellite image of the terrain. It showed clearly that these local hotbeds of activity punctuated the landscape at regularly spaced intervals, as if along a grid. That prompted him to try to answer a deceptively simple follow-up question: Does this patterning actually matter?

Patterns are everywhere in nature, from the ribbons of alpine forests on mountainsides to the complex swirls of mussel beds, but proving whether they influence the fundamental properties of ecosystems has been difficult. Pringle wanted to know whether these patterns “really do affect things like productivity, nutrient-cycling rates, and diversity of living forms.”

In a groundbreaking study published recently in PLoS Biology, Pringle says they do, citing the nonrandom distribution of termite mounds over the Kenyan grassland as evidence, based on his collaborators’ and his own statistical simulations. “Where they exist,” he explains, “regular patterns really do scale up to dramatically influence ecosystem function.” The mounds support dense populations of flora and fauna. Plants grow faster the closer they are to the mounds, and animal abundance and reproductive success dropped off with distance. The termites recycle nutrients and, Pringle and his colleagues suspect, they may also improve the soil by introducing coarser particles that help aerate it, simultaneously promoting water infiltration and retention. The even distribution of mounds is vital to this enhanced productivity, suggesting that the lowly termite plays a substantial ecological role alongside the more charismatic fauna of the savanna such as cheetahs or lions.

Pringle’s study is the first to link spatial patterning to the larger-scale properties of an ecosystem, but he expects that rapid technological advances in other domains (particularly chemistry and molecular biology) will likely reveal similar patterns that may generate further research. Besides satellite imagery, he says, “other kinds of tools—including genetics and, increasingly, geochemical assays—will allow us to shine a much brighter light on how ecosystems are put together and why it matters that they’re put together in that way and not some other way.”

Beyond its importance to ecological scholarship, Pringle’s work has special relevance to both conservation and environmental reconstruction. “Let’s say you’re trying to restore a forest or a coral reef, and to do that you’re planting trees or bits of coral fragment,” he says. “Our results suggest that you want to think hard about the spatial patterning of these transplants—and to remember specifically that even, grid-like, spacing will typically yield the fastest regeneration rates.”