In the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, Interstate 70 cuts from east to west across what wildlife biologists call the Mountain Corridor—a 144-mile-wide swath of mixed habitat flowing north and south between Denver and Glenwood Springs. The corridor is a major throughway for mountain goats, bear, Canada lynx, moose, deer, fox, and other animals roaming in search of food and mates. As traffic on the highway has increased and regional development has claimed more habitat, more animals have died in collisions with vehicles.

To counter this trend, a group of transportation and wildlife agencies in the United States and Canada launched a competition last year to design wildlife crossings for the nation’s roadways. The organizers chose a crossing site near West Vail Pass—one of the deadliest stretches of I-70 for animals—and challenged landscape architects and engineers “to reweave landscapes for wildlife using new methods, new materials, and new thinking.”

Designs arrived from 36 teams in nine countries, representing more than 100 firms. Chairing the five-member international jury that reviewed the five finalists was Charles Waldheim, Irving professor of landscape architecture, chair of that department at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), and a leader in the emerging field of landscape urbanism. “Wildlife crossings, which are common in Europe, are a long-overdue response to the ecological damage the…interstate highway and civil defense systems have done in this country,” he says. Cities, he notes, began to redress the social costs of routing highways through neighborhoods decades ago, but the public has yet to stem the destruction of wildlife habitat and populations by highways in more remote areas.

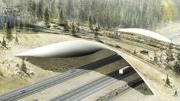

In January, the jury unanimously chose a design called hypar–nature, submitted by HNTB Engineering, of New York City, teamed with Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), a landscape architecture firm founded by the GSD’s Eliot professor in practice in the department of landscape architecture, with input from ecology consultants Applied Ecological Services. The winning design takes its name from its lightweight, super-strong “hypar (hyperbolic parabaloid) vaults”—V-shaped concrete ribs, bent obliquely and pinched at each end—that span the highway. “A wildlife crossing must support loads five times greater than conventional bridges, due to the combination of soils needed to support landscape, plus an allowance for snow and robust landscape growth over time,” explains Ted Zoli, an HNTB vice president who is an expert on bridges. The hypar vaults are an adaptation of the common pre-cast concrete beam, he explains: “Each vault serves as abutment, pier, beam, and slab, all in a single, repetitive element.” The team designed the low-cost, modular structure as a prototype that can be easily modified and replicated in a regional network.

The design does more than simply knit together the natural landscape on both sides of the highway to facilitate wildlife crossing passively. It also distills and intensifies the four main types of surrounding habitat—scree, forest, shrub, and meadow—into discrete corridors that induce animals to cross by providing protective tree cover, areas with open sightlines, and thick plantings of favorite food sources (grasses, sedges, and fruiting shrubs) that extend across the bridge. To keep creatures from straying over the sides, an exposed hypar vault borders each side of the landscape, creating a V-shaped concrete barrier eight feet deep with a 60-degree slope.

At its southwest end, the bridge forms a level plateau between the mid-slope of a ridge and the overpass. The northeast end descends to a seasonal wetland that captures water to attract wildlife. Here animals as large as lynx and coyotes can enter a tunnel to cross beneath the road. Atop the bridge, the bands at each end fan out into the surrounding wild landscape, following routes where ecologists have identified existing animal activity. “Along the edges of these corridors we proposed to fell existing pine trees that have been affected by the pine beetle [a prolific pest],” Zoli explains. “The felled trees are then arranged along the edge of the corridor to serve as both habitat and as a natural obstruction, eliminating the need for conventional fencing.”

MVVA, Van Valkenburgh says, was “essential in merging the imperatives of structural design with the imperatives of ecological systems.” In particular, his firm “provided the landscape framework for the structure developed by HNTB, found low-impact ways to accommodate the grade change on both sides, and created the appropriate conditions for plants and trees to thrive and grow.” MVVA had not designed a wildlife bridge before, he says, but is often called upon to build landscape connections across infrastructure, minimize environmental impact, and work creatively within ecological parameters: “The unusual part was that these concerns were much more in the foreground, whereas the social and cultural use of the landscape, which is usually very important to the projects we undertake, was not really a determining factor.”

Outwardly, the five final designs looked strikingly similar. But the winning proposal, one juror wrote, “is not only eminently possible; it has the capacity to transform what we think of as possible.” Specifically, Waldheim says, the HNTB design “prioritized the flora and fauna over the other considerations, yet the transportation engineering was equally strong and thoroughly integrated—you didn’t see a compromise in which wildlife was secondary to bridge design, or vice versa. The outcome was greater than the sum of individual components.”