Cabot associate professor in applied science Kevin "Kit" Parker and a team of fellow Harvard bioengineers have announced the discovery of precisely how traumatic head injuries damage brain cells, a discovery that offers new hope for soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan wounded by improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Such injuries can result in death or temporary concussions that can produce dangerous hemorrhages or long-term injuries that can lead to early onset of Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s.

“Imagine this blast wave is propagating through the head—like you’re thumping your Jell-O when you’re a kid,” Parker told the Boston Globe. “When it gets to these cells, the cells are stretched and compressed.”

Parker and his team found that when the brain is subjected to a loud, explosive force, fragile tissue slams against the skull, resulting in a surge in blood pressure that stretches blood-vessel walls beyond their normal limit. Published in a pair of recent scientific journals, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and PLoS One, the findings offer the most detailed explanation to date of how a bomb blast damages the brain, ScienceNOW, the online presence of Science, explains. The researchers also discovered that those suffering from brain injuries might be helped by a particular protein inhibitor that plays a role in preventing brain cells from attaching to surrounding tissue in harmful ways.

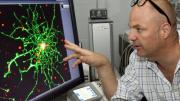

Parker, whose bioengineering breakthroughs in cardiology were profiled in Harvard Magazine in 2009, shifted his focus to brain research after two tours in Afghanistan as a U.S. Army infantry officer. “I kept seeing buddies of mine get hit and thought, ‘All right, I’ll take a look at this and see if I can get an angle on it,’” Parker told ScienceNOW. To conduct their tests, the researchers built a neural network of engineered human blood vessels and rat neurons. They then subjected the network to forces that mimicked blast waves moving through brain tissue, the first step toward a “Traumatic Brain Injury on a chip” that could be used to screen for drugs to treat blast-injured soldiers before long-term damage sets in, reports MIT’s Technology Review.