In the beginning, before there were squirrels in Harvard Yard, the eastern gray squirrel was a shy woodland creature, not an urbanite at all, used to being shot at by frontiersmen and Indians for food or by recreational hunters for sport or by farmers to protect cornfields and orchards from marauding teeth. Through the early nineteenth century, gray squirrels were effectively absent from American cities. The present ubiquity of the arboreal rodents, who often seem to enchant international visitors to Harvard, is explained by Etienne Benson ’99 in a hefty, illuminating article, “The Urbanization of the Eastern Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) in the United States,” in the December issue of Journal of American History. Probably no one has gone into this topic as intensively as he.

Benson earned a Ph.D. from MIT in 2008, was a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard’s Center for the Environment and in the Department of the History of Science, went on to be a research scholar at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, in Berlin, and is now an assistant professor in the history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania. There he is on historic ground. In 1847, Benson relates, three squirrels were released in Franklin Square, then in a fashionable residential neighborhood, and given boxes for food and for nesting, making Philadelphia the apparent pioneer in the introduction of squirrels to urban centers. Boston followed in 1855 by importing a handful of squirrels to the Common, and New Haven had a population of the creatures on its town green by the early 1860s at the latest.

“The urbanization of the gray squirrel in the United States between the mid-nineteenth century and the early twentieth century was a simultaneously ecological and cultural process that changed the squirrels’ ways of life, the urban landscape, and human understandings of nature, the city, and the boundaries of community,” writes Benson. “Squirrels were part of the new complex of human-animal relationships that emerged in the American city at the turn of the twentieth century, as laboring animals were replaced by machines and dairy, meat, and egg production and processing were shifted to the urban margins.” Evidence in newspapers, scientific journals, diaries, and other sources reveals, Benson finds, that the squirrel came to be seen “not merely as an interesting object of nature study but also as a morally significant member of the urban community.”

Because squirrels “were nondomesticated but appeared to be responsive to and solicitous of human charity,” writes Benson, “they held a special place in [urban reformers’ and humane activists’] vision of a more-than-human community.” It became necessary to feed, house, and protect them. Many decades later, ecologists would decide such cosseting was bad, but when the first gray squirrels arrived in Harvard Square about 1900, emigrating over the course of a decade from woodsy Mount Auburn Cemetery about a mile away, Harvard built nest boxes for them in the Yard elms and distributed bags of peanuts over the winter, as did the keepers of many city parks and squares. Professor Charles Eliot Norton offered children 50 cents for each bushel of acorns they gathered in the woods, which he had distributed to squirrels throughout Cambridge. A wide variety of individuals, Benson notes, “shaped the moral-ecological character of urban public space…[where] even the least powerful members of human society could perform the virtue of charity and, in doing so, display their own moral worth.”

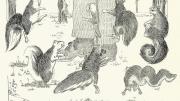

One exempts from charitableness the Harvard student who drew the cartoon below, published in the Harvard Lampoon in 1903, about the begging of the Yard’s recently arrived squirrels. Writes Benson, “[T]he animals’ demands put them in the same rank as shameless, albeit sometimes entertaining, human beggars.…[The cartoon] implicitly compared the Yard’s squirrels, depicted in acrobatic poses while begging a student to ‘scramble a nut,’ to the ‘muckers’ of Harvard Square—poor boys who were known for asking well-heeled students to ‘scramble a cent.’” The student newspaper, the Crimson, praised the cartoon as providing “something really new and refreshing on the squirrel question.”