The Canada-United States border, the longest shared by two countries (5,525 miles, including Alaska), is uniquely calm. But establishing it was a protracted, unpeaceful pursuit, ultimately aided by one of the longest Harvard library loans on record.

The Treaty of Paris (1783), recognizing U.S. independence, defined the boundary ambiguously: “From the North West Angle of Nova Scotia, viz., That Angle which is formed by a Line drawn due North from the Source of the St. Croix River to the Highlands,” and so on, as the Map Collection’s Joseph Garver, librarian for research services and collection development, helpfully points out. But what was that angle? Where were the highlands? Did the Atlantic Ocean include the Bay of Fundy? Surveying availed little; the issues were political.

In 1828, the two countries submitted their claims to an arbiter, King William of the Netherlands. As evidence, the U.S. negotiators borrowed 22 maps and books from Harvard, more from the Boston Athenaeum and Massachusetts Historical Society, and shipped them off to The Hague.

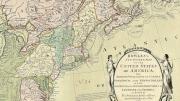

Each Harvard document bore an exhibit number and was inscribed with the terms of the loan (see the inset from the Peter Bell map of 1772). The British, seeking access to the interior via a military road from the Maritimes to Montréal, favored a southerly division, explains Garver, who has curated a 2012 exhibition of and lectured about the maps. The Americans imagined a line far north and east, close to the St. Lawrence (see Carington Bowles’s “new pocket map” of 1784, left, with its many other boundary eccentricities, to the modern eye). The king’s 1831 compromise dissatisfied the young (1820) state of Maine and its parent, Massachusetts (which still had vast landholdings there). The United States withheld assent.

After repeated threats of renewed belligerence, Secretary of State Daniel Webster, LL.D. 1824, and Lord Ashburton, facing the District of Columbia’s wilting summer heat, negotiated a resolution in 1842. (The rhetoric had also become hot: a British surveyor denounced an American’s work as “the most inflated humbug that ever flourished in the region of bombast.”)

In 1843, President Josiah Quincy wrote Webster for the loaned maps; nine were returned. President Edward Everett inquired again in 1848, and nine more reappeared, including Bell’s. President Jared Sparks secured the rest, after U.S. president Millard Fillmore ordered a search of the State Department files (Everett was then secretary)—in 1853, a quarter-century after they were checked out.