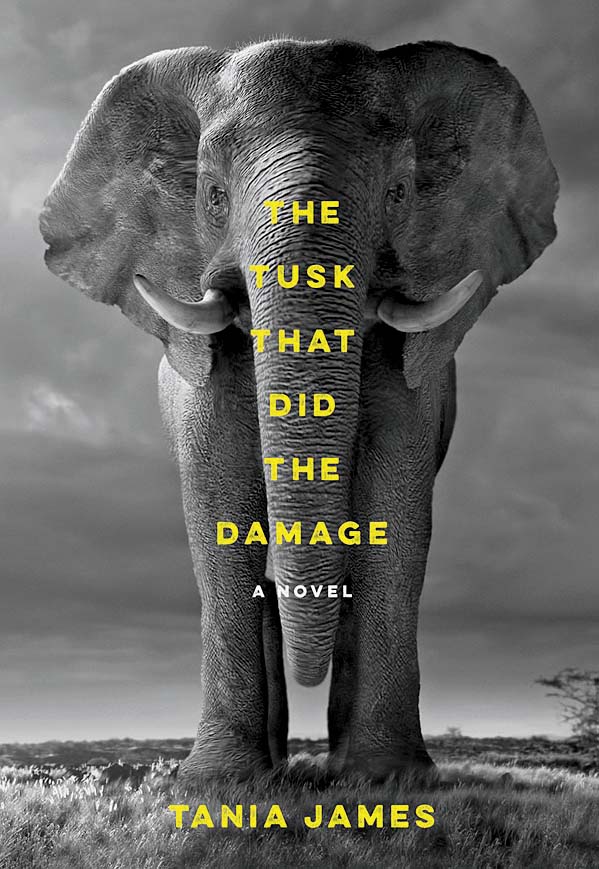

“Never write from an animal’s perspective,” admonished the fiction-writing manual that Tania James ’03 read while preparing to teach a writing workshop. At that moment, she realized the magnitude of the risk she had taken in her then recently completed novel. In The Tusk That Did the Damage, she braids the perspectives of three narrators: Manu, an Indian man pulled toward poaching by the influence of his brother; Emma, an American woman whose attempts to make a film about the dangerous trade are equally shaped by ambition and naiveté; and the Gravedigger, an elephant who becomes homicidal after suffering years of human cruelty.

Critics and readers have focused almost entirely on this last character, though James devotes equal space to all. She says now that she’s glad she was relatively unaware of the perceived formal difficulties of writing an intimate portrait of an animal; the pressure might have spooked her. She began the novelwhile in Delhi on a Fulbright grant. In search of ideas, she picked up To the Elephant Graveyard by Tarquin Hall, a nonfictionaccount of a rogue elephant who buried the humans he killed. “That’s an interesting and strange personality quirk,” James recalls thinking. “I wanted to explore the psychology behind it.”

Manu and Emma speak in a conversational first person, but the Gravedigger’s perspective is presented in an image-laden third person. His narration is complex, but also clearly non-human, being largely devoid of the moral reasoning used by the other two narrators. Rather, the elephant’s emotions, intuitions, and memories are conveyed solely through vivid sensory experience:

The sky above him wild with stars, and still the Gravedigger could not sleep. He felt a smoldering under his skin, an ache in his tusks, until the breeze brought him the scent of the Old Man. That invisible presence, however brief, was a steady palm to the Gravedigger’s side.

“When I was writing the book,” James recalls, “I didn’t feel any one perspective was my favorite. I was trying to create a tapestry of voices.” Yet when she discusses the characters, it becomes clear that the Gravedigger’s perspective was the center from which the novel unfurled. About Manu, James says, “Once I got into a voice for the Gravedigger, I thought, ‘This has to involve a person, because one thing that really interests me is human-elephant conflict.’” Emma’s perspective came even later, from an interest in “a larger context of conservation in India…I wanted the novel to contain conversations that were grounded in ideas.”

To locate these ideas, she researched the conditions in which the ivory trade occurs. Forces like rapid urbanization, poverty, and population growth compound to put pressure on vulnerable people, some of whom—as illustrated through Manu’s story—become poachers. During the writing process, says James, “My thinking about who’s responsible was constantly being challenged.”

She also traveled to the state of Kerala, in India—the setting for the novel, and her family’s original home. There she interviewed former poachers who now work as guides in a wildlife park, thanks to a government-run conservation program. “In the news,” James says, poachers are “referred to as a sort of criminalized nonentity, but they’re really the lowest rungs on the ladder of a very broad system.” She mentions her initial surprise at learning that the United States is the world’s second-largest importer of ivory products. “Everyone talks about China,” she notes, “but we have our own complicity.” To reflect these interconnected political and economic forces, James wrote her multiple nested narrators so that each represents a small part of a vast social context. For her, characters are not only individuals who act within the novel—they are figures balancing and bolstering the ideas behind its structure.

This affinity for structure comes, in part, from her training in film. At Harvard, James studied documentary filmmaking in the department of visual and environmental studies, while also taking creative writing courses. After graduation, she made a film in Mumbai, then earned an M.F.A. in fiction at Columbia. “The process of learning how to edit film informed the way I thought about editing fiction,” she explains, attributing her tendency to be “relentless about finding an arc and structure” to her experience of piecing together footage.

She has struggled with an excess of that impulse, as well. Her undergraduate writing teacher, Gish Jen ’77, RI ’02, once commented on a piece: “I can see you at every moment in this story knowing what the next moment is going to be. You should try to loosen the reins of control a little bit, let the story discover itself.” James remembers the words with fondness: “I didn’t totally understand her at the time, but in retrospect, that was a major piece of advice.”

In Tusk, she has taken that counsel to heart. Before she began the rest of the novel, she focused on crafting a voice for the Gravedigger that remained mysterious even to her. “That’s when I feel most interested in a character,” she says, “when I think I know someone, but they could actually do something surprising at any moment.” In the novel, Emma’s voice—as a filmmaker who tries, often in vain, to shape narratives beyond her control—plays as counterpoint to the Gravedigger’s unpredictability. These dueling artistic impulses hold the narrative together and keep it whirling to its tangled conclusion.