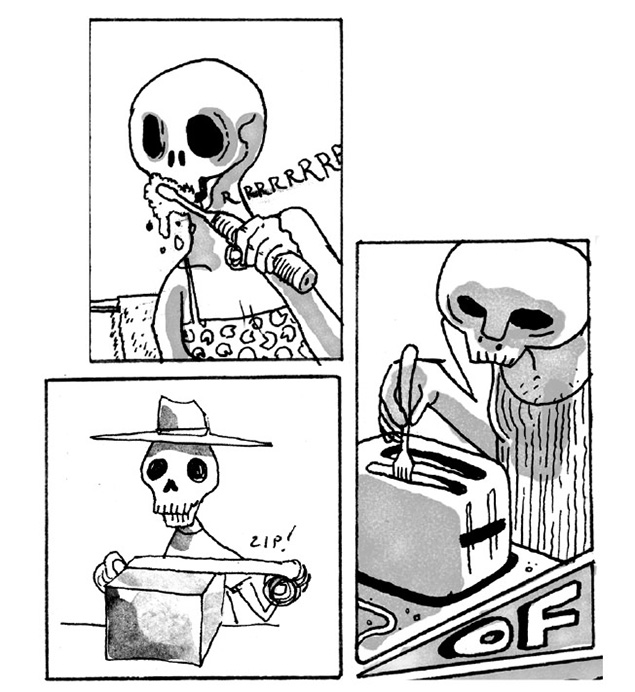

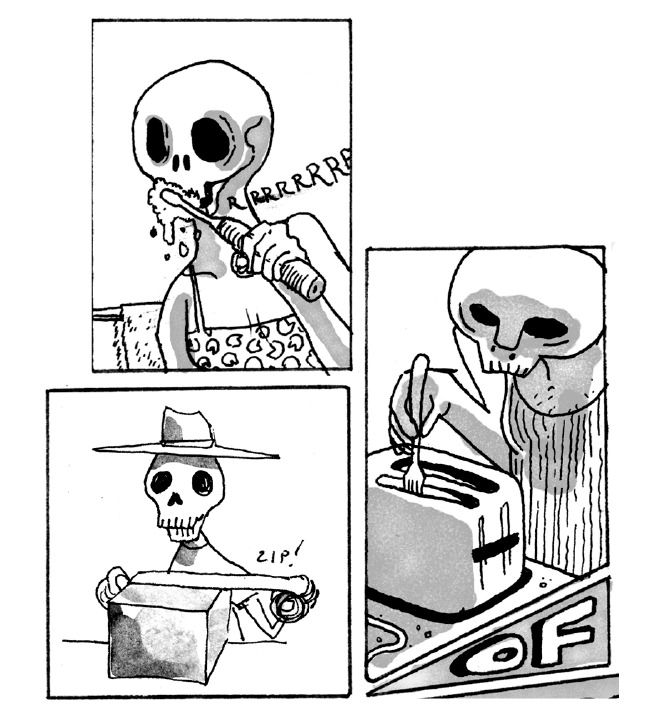

Taping a package closed, shaving an armpit, coaxing bread out of a toaster with a fork, sitting on a toilet while staring at a phone—chin resting in hand, pants puddled around ankles. In her comic drawing “Faces of Death,” Andrea Tsurumi ’07 imagines skeletons performing each of these banal activities. No words explain the message: Is this a parallel universe? A setting for a cautionary tale? Are death’s most ordinary moments just x-rays of life’s? Equal parts grave and goofy, the image captures Tsurumi’s specialty: life observed and shown as absurd.

In her work—which includes one-off drawings, visual book reviews, picture books, and illustrations—Tsurumi pushes situations to their extremes, asks “What if?” and then adds fanciful elements. “If I give my brain enough stuff to chew on,” she says, “something random will pop out.” For example: “I love watching people choose desserts. It’s a very naked and vulnerable indulgent moment, where someone who’s very serious will be, like, ‘Oh wait, they have coffee cake!’”

“There’s no way to get ahead of Andrea’s brain,” says Tsurumi’s literary agent, Stephen Barr, who is guiding the development of her forthcoming children’s book, Accident. In it, an armadillo knocks over a jar of strategically placed red liquid and rushes around encountering other animals who are experiencing their own accidents. Barr describes Accident as a “high-calorie picture book,” dense with jokes and detail; Tsurumi says Accident is “Richard Scarry-crazy”—and the animals with attitudes, colorful liveliness, and earnest sense of wonder in her images do seem descended from his drawings of Busytown.

Details from Faces of Death. (Click to see a gallery of images from Tsurumi's work.)

Images courtesy of Andrea Tsurumi

Details from Faces of Death

Images courtesy of Andrea Tsurumi

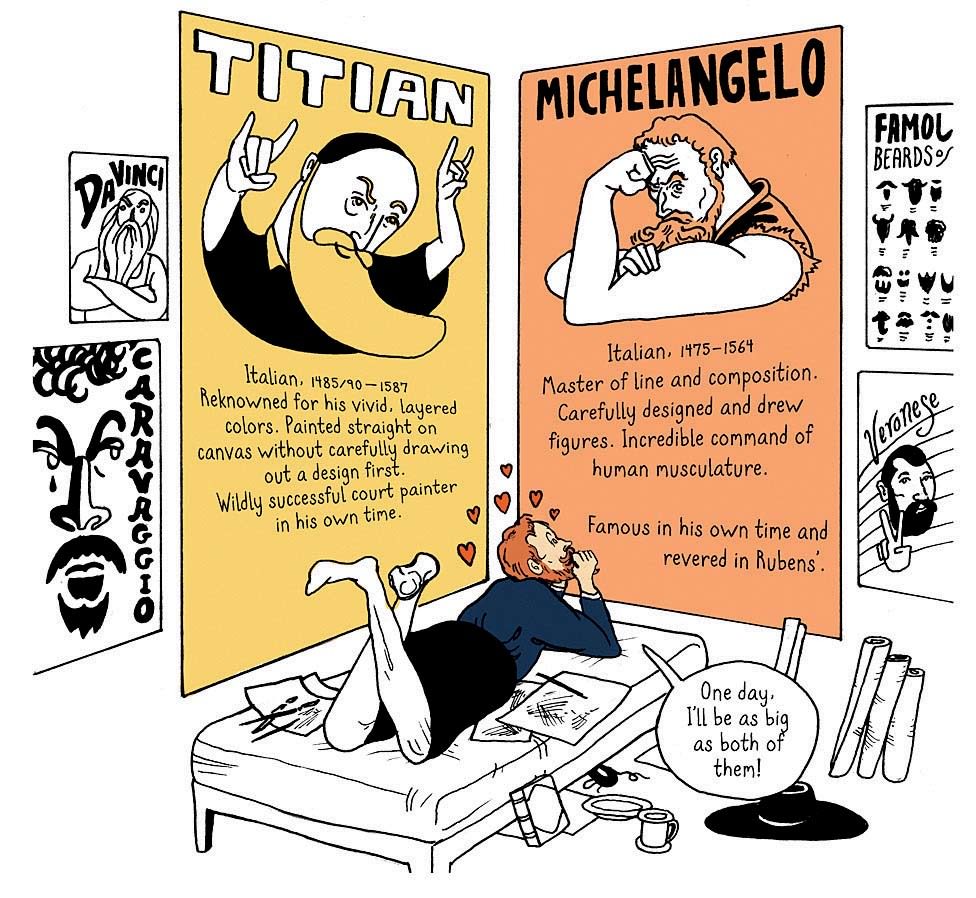

Detail from Challenging the Gods: Rubens Becoming Rubens,Tsurumi's contribution (adapted from curator Christopher D.M. Atkins's essays) to Prometheus Eternal

Detail from Challenging the Gods: Rubens Becoming Rubens,Tsurumi's contribution (adapted from curator Christopher D.M. Atkins's essays) to Prometheus Eternal

Image courtesy of Andrea Tsurumi

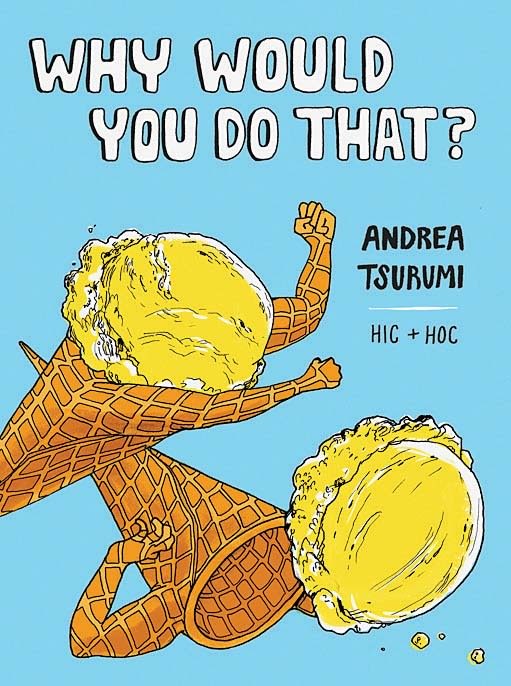

The cover of Tsurumi's first book, which documents her many enthusiasms

Image courtesy of Andrea Tsurumi

In Tsurumi’s work, details explode from the page. Her cheeky maximalism packs a visual punch, whether she’s using hard lines or a hazier, impressionist approach. Encountering it can be as overwhelming, trippy, and thrilling as visiting a new place—allowing the reader to see things in a more fun and zany light. Her sensibility, delighting in what might seem mundane, can resonate with people of all ages. It’s almost as if Tsurumi is sharing secrets of the world’s possibilities, and it’s exciting to behold—even if how she discovers these secrets and develops them on paper can be difficult to pin down.

Tsurumi’s first book, Why Would You Do That? exhibits her dark humor and tendency toward surrealism. Published in May, this playful assortment of her comics and drawings also documents her various obsessions: dogs, books, history, and food. The cover depicts two ice cream cones fighting: one, cone-fists balled up at the end of stocky cone-arms, has just punched the other’s scoop-head off. Within the book, fluffy bichons become trichons become tetrachons, like Cerberuses with an extra profusion of heads; a food photographer shoots breaking news for a newspaper; a Civil War battle is imagined with desserts in “Cake vs. Pie.” The latter is gleeful and gruesome: cakes on roller skates aim arrows at multi-legged pies, a fortune cookie spars with a muffin, and a jelly roll bashes a cinnamon roll. Later, an ice-cream orderly empties a bed pan while a biscotti doctor stands by, splattered in guts. Tsurumi commits to every joke, and her attention to detail in realizing these conceits keeps them from becoming precious.

For her contribution to Prometheus Eternal, an art anthology showcasing a recent Philadelphia Art Museum exhibition, Tsurumi adapted the curator’s catalog essays into a historical comic. Narrating why and how Rubens painted Prometheus Bound, she depicted the old master as a child, doing pushups and nursing schoolgirl-like crushes on Michelangelo and Titian. She takes humor just as seriously as she does her subjects, which makes her shy away from treating anything too reverently. Humor can help readers access unexpected ideas and ways of thinking, she says: “It’s a great horse that can bring you into a common experience, which is very uniting and empathetic.”

She recently moved from New York City to Philadelphia, where she’s enjoying the relative calm. New York provided endless material for inspiration, as shown in her people-watcher diary comic Eavesdropper, which records happenings in the city. But the relentless pace grew over-stimulating. It turned her off as an observer, she says, and she grew numb to her environment—dangerous to an artist whose job requires paying close attention to what’s going on around her. Tsurumi’s dedication to her work prevents her from moving through her days on autopilot. It keeps her mind fed, imagination active, and art exuberant. “Art is a way to fight the shorthand,” she says. “To quote Vonnegut—oh god, I’m quoting Vonnegut—art is not a living, it’s a way to live.”