On a recent visit to Broad Street, the heart of New Britain’s “Little Poland,” not a word of English was heard. Customers lined up for kielbasa at Krakus Meat Market, and picking out blintzes and cukierki czekoladowe (chocolate candies) at Polmart, or crowded into Kasia’s Bakery for babka and puffy donuts called pączki—all spoke Polish.

“And it’s not just [in the] markets and restaurants, it’s bank tellers, accountants, and doctors, art galleries. This is becoming the cultural Polish center for all of New England,” says bilingual attorney Adrian Baron, president of the Polonia Business Association, formed a decade ago to help focus revitalization efforts begun in the late 1990s. “This area was littered with pawn shops, a strip club, and empty storefronts,” he says. Even when he relocated his law office, Podorowsky, Thompson & Baron, from Hartford to Broad Street in 2006, “There was a heroin dealer doing business on the front steps. Today, there’s a school bus stop, and I put in a welcome bench for parents waiting for their kids.”

Children in traditional dress perform at the Little Poland Festival.

Photograph courtesy of Little Poland Festival, New Britain, Connecticut

New Britain, about 15 miles southeast of Hartford, was a Colonial-era settlement, but rose to prominence as a manufacturing center, dubbed the “Hardware City,” when companies like P&F Corbin Company and Stanley Works (now Stanley Black & Decker, still headquartered there) were founded in the mid nineteenth century. Poles began arriving in the late 1800s and joined other immigrants—Irish, German, and Italian—working in the booming factories. The community was soon buttressed by the neo-Gothic Sacred Heart Church, built in 1897, which looms large on the Broad Street hill and still holds services in Polish. Another wave of Poles arrived after World War II, then a third influx associated with Polish independence in 1989.

Immigrants were once so crucial to New Britain commerce that company representatives sought to recruit them as they disembarked from ships in New York City, says Min Jung Kim, director and CEO of the New Britain Museum of American Art (NBMAA). The museum traces its roots to the New Britain Institute, founded in 1853 to foster learning and cultural awareness among the new arrivals. In 1903, John Butler Talcott, a former mayor, chair of the Institute’s building committee, and founder of the American Hosiery Company, donated $20,000 in gold bonds for an art-acquisition fund. This transformative gift was part “of a civic and cultural consciousness that began to develop in the first part of the nineteenth century in prosperous cities in the Northeast and gradually spread throughout the country,” Kim wrote in “American Art in the 21st Century: Building Bridges, Not Walls,” for Art New England (May-June 2017). “In short, the NBMAA was uniquely positioned to reflect the new, unifying, and ‘American’ visual rhetoric.”

Local leaders also commissioned the adjacent Walnut Hill Park in 1870, now on the National Register of Historic Places. It was designed by the office of Hartford-born landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, A.M. 1864, LL.D. ’93, as a respite for residents—and is still a picturesque place for exercising, walks, public events, and simply relaxing. In 2009, the Friends of Walnut Hill Park Rose Garden organized to re-create and maintain that garden (originally added in 1929) by moving it to the courtyard by the World War I memorial and planting more than 800 bushes, representing 75 varieties, as a purposeful symbol of the city’s diverse population.

The NBMAA was the nation’s first institution dedicated solely to American art, Kim says; its permanent holdings stand at more than 8,300 works, including pieces by the Connecticut-raised Sol LeWitt. It also owns prime examples of Colonial portraiture, the Hudson River School, and works by Winslow Homer, Mary Cassatt, Thomas Eakins, Childe Hassam, and Thomas Hart Benton.

In 2015, an addition greatly expanded gallery and classroom space. The museum continues to serve as a vibrant community resource, offering lectures, concerts, and classes for all ages. “NEW/NOW: Francisca Benítez” (through April 29) highlights video and photographic works exploring the power and diversity of sign languages and deaf culture, including a collaborative project with children at the American School for the Deaf, in West Hartford, the birthplace of American Sign Language. The museum also holds upward of 200 original oil paintings created for inexpensive pulp-fiction publications such as The Shadow and Doc Savage, hugely popular from the Great Depression through World War II. The sensational graphics often depict archetypal characters—barely clad “damsels in distress,” “heroic” tough guys—engaged in adventures, mysteries, and science-fiction narratives that influenced a collective understanding of American values and success stories.

An image from an exhibit on American Sign Language featured at the New Britain Museum of American Art

Francisca Benítez, América 2016 courtesy of the New Britain Museum of American Art

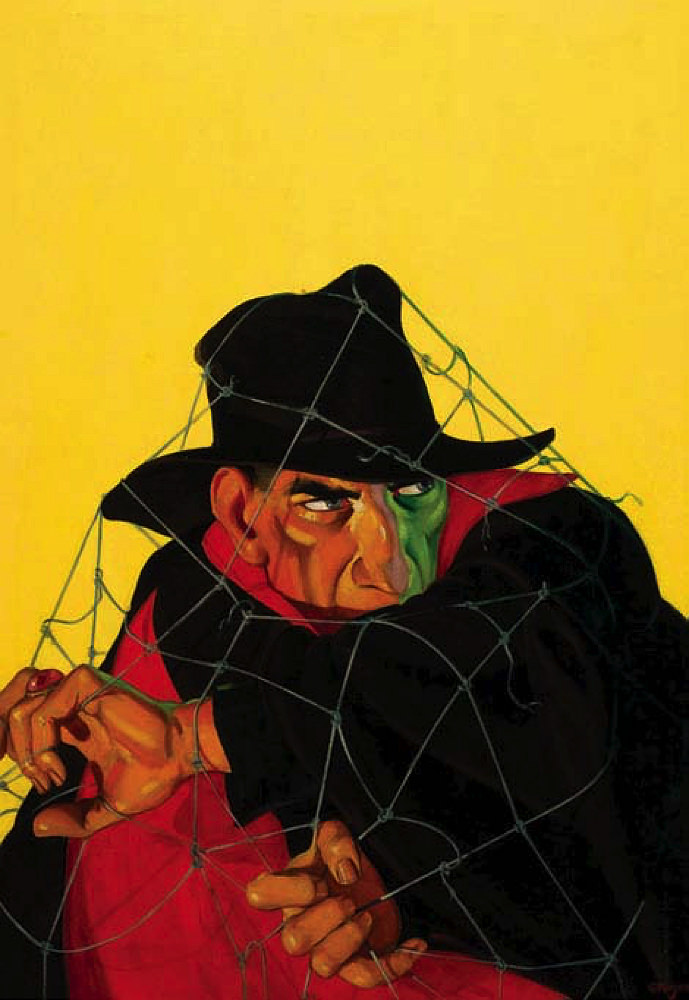

This 1933 painting for The Shadow Magazine is among more than 200 pulp-art works held by the New Britain Museum of American Art.

An illustration for George Rozen’s "The Grove of Doom," from The Shadow Magazine, September 1933, The Robert Lesser Collection of Pulp Art, 2009.22.51LIC, Courtesy of the New Britain Museum of American Art

Kim wants the museum to reflect the “rich and varied” aspects of American culture and experiences, and on mounting shows that speak to local and regional residents. With a Polish community constituting about 20 percent of New Britain’s nearly 73,000 residents, the museum has hosted events and exhibits over the years exploring Polish and Polish-American arts and heritage, she explains. Last year’s “Vistas del Sur: Traveler Artists’ Landscapes of Latin America from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection,” which featured more than 150 works created between 1638 and 1887, together with English and Spanish exhibit texts, reached out to a Hispanic community encompassing nearly 44 percent of city residents. “Ghana Paints Hollywood” (through February 19) presents hand-painted African movie posters for U.S. films from the mid 1980s through the early 1990s that represent a Golden Age of pre-commercial, “imagination-driven” advertisements by individual artists. Such shows purposely “flip the gaze,” Kim says, because the focus “is not always about our declaration of what American art is, but about opening ourselves up to other global representations of us—and that only contributes to a more informed consciousness about what American art is and how America is perceived.”

In May, the museum’s gaze returns to New Britain’s industrial legacy with “New/Now: Paul Baylock.” His works integrate iconic factory and hardware motifs reflecting his own experiences growing up in the city, where he was part of an Irish-Lithuanian family of 10, and taught art in the public schools for decades. He also witnessed the postindustrial decades of economic challenges, demographic shifts, and the blight that still plagues some sections.

Yet in an age when many ethnic neighborhoods that coalesced around that long-ago heyday are gone, Little Poland, designated in 2008, is thriving.

And it’s serving as an inspiration elsewhere. The New Britain Latino Coalition is developing the “Barrio Latino” (renamed a few years ago) around Arch Street, which holds a cluster of Latin-American organizations and businesses, including the Criollisimo Restaurant and the Borinquen Bakery. “We’re in the infant stage,” says coalition chairman Carmelo Rodriguez, “working on getting more businesses to the area, and with landlords to fix up their buildings.” The city already hosts annual Latino and Puerto Rican Festivals; this spring, following a six-year effort, the new Borinqueneers Monument (honoring the 65th Infantry Regiment from Puerto Rico, the last U.S. Army unit to be desegregated) will be dedicated in a new city park, Rodriguez says.

“New Britain is a melting pot of cultures,” he continues, “we have Polish and Central and South Americans, and Laotians and Vietnamese and Yemeni. You name it, we got it. We have seen the fruits of their hard work in Little Poland, and it’s awesome. We are all proud of each other here. It’s not about competitions.” Many city residents and officials are also increasingly joining forces to clean up and revitalize other areas—and the Polonia Business Association wants to help. “We try to be inclusive and support each other,” Adrian Baron says, “because helping the city helps all of us.”

Still, these projects take time. Lucian Pawlak, who settled in New Britain with his emigré parents in 1956, is credited with spearheading renovation and eradicating gang activity in Little Poland when he was mayor, from 1995 to 2003; the recently refurbished sidewalks and new street lamps were improvements he began pushing for in 1999. He and Baron agree the still emerging transformation has hinged, in large part, on a loyal base of second- and third-generation Polish Americans (and recent immigrants) who patronize the professional businesses, markets, and restaurants—like Belvedere Café, Staropolska, and Polonia Taste—even after they move to nearby communities. “The place is a way for many Polish-Americans to reconnect with their heritage,” Baron says. “They’re in language classes, buying books and music, and sampling the food.” But the reversal also reflects the locals’ initiative, he adds: “We don’t wait for things to happen. Instead of complaining to the city about cleaning up an empty lot, we’ll clean it up ourselves. If there’s a problem with a drug dealer on a corner, then we’ll call the police and say we’ve got footage, we’ll speak out in court.”

Such active participation has helped bolster the annual Little Poland Festival (on April 29 this year), where performances by Polish polka, rock, and jazz bands, by the Polish Language School, and by traditional Goral singers and dancers from southern Poland, among others, now draw thousands of people. “And there’s great food,” says the organizer, Pawlak. “Everything from pea soup that your spoon stands up in to, obviously, parówki, kapusta, pierogi, and golabki”—hot dogs, sauerkraut with bacon and onions, dumplings, and stuffed cabbage, respectively.

“It’s very heart-warming,” he adds, to see this “amazing turnaround.” He remembers arriving in New York Harbor as a boy. “We were at the port and company agents picked us up and dropped us off at a 13-story hotel—I had only ever known a hut. None of us spoke English, and my father had two slips of paper because he had a sponsor in New Britain and one in Chicago.” He figured out that the train ride to Connecticut was three hours, while Chicago took 20, “and chose New Britain, because my brother was sick. When we arrived, the agents threw us in a two-family house, and there were eight other families living in that house, too. It was terrible,” he says, “but that’s another story.”