In the early fall of 1943, World War II was raging in Europe and on islands in the Pacific. At home, many Americans were growing weary of a war that seemed never to end. Many others were also tired of the war but determined to fight on to victory. Amid this mixed mood—somber and also resolute—the prime minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill, discreetly boarded a special train in Washington’s Union Station late in the evening of September 5. The PM’s wife, Clementine, his 20-year-old-daughter Mary, his personal physician, Lord Moran, his trusted bodyguard, and a number of British officials accompanied him. They were bound for Boston, where the next day Harvard University intended to award Churchill an honorary degree. Anticipating the event and the honor, he had great expectations.

However, after spending the evening at a White House dinner with President Franklin D. Roosevelt where everything seemed to go passably well between the two friends, Churchill seemed downright preoccupied, even petulant. Clementine Churchill had once remarked that two weeks before delivering an important speech, “Winston had never been pleasant company,” and in this case, the prime minister confessed that he had not yet completed his speech for the next day. From 11 that night until 2:45 the next morning, he sat in his drawing room in the jiggling, speeding train and wrote out the final draft of his talk accepting the Harvard degree. Lord Moran, ever attentive to his charge’s health, thought the ill humor might have been caused by some kind of a bug; in his diary, he commented, somewhat haughtily, “For some reason, which I cannot fathom, he is taking the speech he is to make at Harvard very seriously.”

In fact, Churchill had good reason to do so.

Unsurprisingly, the key person initiating Harvard’s invitation to Churchill was President Roosevelt, A.B. 1904. As governor of New York State, he himself had received a Harvard LL.D. in 1929 and, thanks to the probable prompting of Churchill, an honorary degree, in absentia, from Oxford in 1943. For all that Churchill had done for him, FDR realized, he clearly had some obligation to return the favor. There were also good political reasons for Roosevelt to act. More than ever, was a vital wartime imperative to keep the friendship between the two statesmen in “good repair.” Consequently, the American president actively explored various ways and times to reciprocate by encouraging the award of a Harvard honorary to Churchill

Early in 1943, President Roosevelt contacted President James Bryant Conant, who had long admired the PM and was immediately enthusiastic about the idea. But there was an immediate problem. By long tradition, most Harvard honorary degrees had been awarded only at June Commencements and it was clear that, given the vicissitudes of war, Churchill’s schedule could rarely if ever accommodate such a limitation. Furthermore, another strict rule (rarely broken) is that all honorary-degree candidates must be present in Cambridge to receive their awards. But knowing full well this statesman’s great role in history, the President and Fellows of Harvard College voted on May 26 to extend an open-ended invitation to Churchill to receive an honorary doctor of laws degree “whenever he could find the time to come to Cambridge.”

Churchill’s staff reacted at once. Realizing that he would be attending the August 1943 Quebec Conference with President Roosevelt and Canadian prime minister Mackenzie King, they helped arrange for the rare Harvard “out-of-season” ceremony to take place the following month in early September.

What about the general subject of the speech, so much on the mind of the PM before he arrived in Cambridge? In his memoirs, Closing the Ring, the fifth volume of his postwar chronicle of World War II, Churchill mentions explicitly his intentions. It was to be an occasion for a public declaration to the world of Anglo-American unity and comity. More than that, it was an opportunity for him to explore “the considerable factors” that tied together these two great allied peoples: the bonds of law, language, literature, blood, and history.

In his speech, Churchill demonstrated that he meant to stir his Harvard audience with an awareness of 1943 as a critical moment in the history of the war that now confronted both Great Britain and the United States. Although many desperate battles remained to be fought in Europe—the Normandy invasions in 1944 and the unexpected Battle of the Bulge in 1945—it was clear by the autumn of 1943 that the tide of war had plainly begun to turn. It was what Churchill called “the hinge of fate”—where the outcome of the war could have swung either way—but in the end proved to be an opening door to an eventual Allied victory.

But there was also a more immediate context. In 1943, reacting to the fast pace of world events, allied leaders had met constantly with each other, in five major conferences. At the Quebec Conference, Churchill, Roosevelt, and Mackenzie King had discussed both the successful Allied invasion of Sicily in July and the forthcoming Allied landing on the Italian mainland. (In fact, the mainland landings at Salerno were taking place on the day Churchill spoke.) All this was very much on his mind as he came to Cambridge, and it is known from his personal records he was also thinking of the prospective, possible surrender of Italy to the Allies. (Secret negotiations were already taking place.) Although Churchill made no mention of the impending surrender in his speech, the impact of such an historic and fortunate event was clearly evident in the optimistic tone, and, sometimes, bravado of his Harvard speech.

on the morning of September 6, an entourage of Boston dignitaries awaited the train’s arrival at a special siding in the Boston and Albany’s Beacon Park rail yards in Allston, among them Governor and Mrs. Leverett Saltonstall and President Conant and his wife, Grace. Churchill and Conant had known each other in Washington, so the welcome on the train platform was cordial all around.

A few security officials mingled easily with the distinguished visitors, a relatively light showing, compared to that accorded in later years to other famous visitors to Harvard. But there was a reason for this apparent minimum of security: the Harvard Corporation had decided not to make any prior announcement of the visit. (Formal invitations to attend the event in Sanders Theatre referred only to the visit of a “distinguished world leader.”) No direct leaks had occurred, and therefore no major security seemed necessary at the station. But rumors still abounded. A week in advance, Harvard’s faculty and student body were avidly discussing possibilities. Three days before the event, members of the military in training at Harvard were informed that it really was Winston Churchill who would be arriving at Harvard. They were all sworn to secrecy and there were no leaks.

Some time after the train’s arrival, however, security increased dramatically. Special details of Secret Service agents, state and city police, and the Harvard police arrived and escorted the Churchill party across the Charles River to the Conants’ official residence in Cambridge. Churchill rested as best he could—one wonders how well he ever rested in his restless life—and began work again on his speech. Striding around the parlor of the residence, he rehearsed his speech out loud until he was finally satisfied. Mrs. Conant had been told to distribute a large number of ashtrays around the living room, and later reported they were all well used. (Several days afterward, she learned that some of the maids had confiscated the cigar butts as valuable souvenirs.)

At 11:30, the Churchills were taken to Sanders Theatre, where the ceremonies began promptly at noon. The PM—unusually relaxed, even jovial—was dressed resplendently in an Oxford Doctor of Civil Laws robe, bright scarlet in color, providing vivid contrast to the surrounding crimson gowns of Harvard faculty members on the stage. (Selecting this particular robe for the ceremony was Churchill’s very late decision and finding one, the responsibility of the University Marshal’s office, was not easy; just in time a suitable robe was borrowed from a British faculty member at Princeton.) Completing his attire was a quaint, black-velvet, floppy hat, a British tradition for those with certain doctoral degrees. (Some observers remarked the hat looked quite amusing on him.)

Sanders Theatre was packed with 1,300 people in the audience and 100 more dignitaries on stage, including members of the Corporation, Overseers, faculty members, administrators, and distinguished guests from Cambridge, Boston, and beyond. A few students were present in the audience, but many more stood outside in the Yard with bystanders, listening to loudspeakers carrying the ceremony live. The speech was also broadcast over several American networks and to Great Britain over the BBC.

Then as now, awarding honorary degrees at Harvard was a fairly standard but also highly ritualized ceremony. First, the University Marshal read a short description of the candidate’s career and high distinction. Then the president read an even briefer but extremely carefully crafted citation—a single sentence that ended with a felicitous, even Churchillian, climax:

“Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill, Doctor of Laws.

An historian who has written a glorious page of British history; A statesman and warrior whose tenacity and courage turned back the tide of tyranny in freedom’s darkest hour.”

(In fact the last two words were Churchill’s own.)

President Conant then handed Churchill a copy of his LL.D. degree in a leather folder and ushered him to the podium, where the PM began his 40-minute speech. A recording confirms that he displayed some of his customary eloquence. His words and their cadence resounded throughout Sanders Theatre.

Although never regarded as one of Churchill’s truly memorable orations, the speech was an exceptional rendering of what he aimed to tell his American audience at a critical moment of World War II. It contained some striking, memorable passages—“The price of greatness is responsibility” and “The empires of the future are the empires of the mind”—and its gorgeously written concluding paragraph, according to eyewitnesses, greatly stirred the audience. Even today, reading the words at the end of his speech can give rise to deep emotions, especially for those of us forced to live our own lives in another period of tempestuous world history.

Churchill began by expressing his pleasure at being present once again in “academic groves” “where knowledge is garnered, where learning is stimulated, where virtues are inculcated and thought encouraged”—a perfect place “to look out upon the world in all its wonder and in all its woe.”

But he went on to observe that this idyllic world has been recently transformed, as during World War I, into a vast arsenal for the waging of war. “How could this be?” he asked, and answered: “The price of greatness is responsibility. If the people of the United States had continued in a mediocre station, struggling with the wilderness, absorbed in their own affairs, and a factor of no consequence in the movement of the world, they might have remained forgotten and undisturbed beyond their protecting oceans....” But fortunately for the world, Americans had chosen to become deeply involved in its problems, and as a consequence America had risen to become “the leading community in the civilized world....” What needed to be recognized by the youth of both America and Great Britain was that there could be no stopping now of the coming battle, a battle whose end must be either “world anarchy or world order.”

Then Churchill introduced his main theme: Americans must know that hope does exist for their ultimate victory, but it must come through their partnership with the British Commonwealth. He offered powerful arguments to support his point. “Law, language, literature—these are considerable factors. Common conceptions of what is right and decent, a marked regard for fair play, especially to the weak and poor, a stern sentiment of impartial justice, and above all the love of personal freedom.... We hold to these conceptions as strongly as you do.”

He went on to ask: Who are we fighting against? His answer: “We do not war primarily with races as such. Tyranny is our foe, whatever trappings or disguise it wears, whatever language it speaks, be it external or internal, we must forever be on our guard, ever mobilized, ever vigilant, always ready to spring at its throat. In all this, we march together.” Then, as if remembering once again where and to whom he was speaking, Churchill defined the battlefield arenas as “the fields of war or in the air, but also in those realms of thought which are consecrated to the rights and the dignity of man.”

As if to prove that genuine cooperation between the two nations is possible and will lead to victory, he discussed the vigorous cooperation between the members of the British and U.S. combined Chiefs of Staff Committee: “a wonderful system....There never has been anything like it between two allies.” The committee, he suggested, might in the future serve as a kind of model for peacekeeping among all nations of the world.

More quixotically, toward the middle of his speech, Churchill suddenly drifted off into the backwater of a pet project: introducing in both countries the teaching of a new and simplified language called Basic English, with a vocabulary of only 850 to 2,000 words, yet more than adequate to convey the most important and even complex ideas. Basic English, he suggested, could in the postwar world enhance the accurate communication of old and new ideas; facilitate transactions of all kinds of business operations; and help minimize international misunderstandings growing out of the ambiguities and misuse of traditional languages. He had discovered that Harvard had promoted the concept of Basic English in the secondary schools of Boston and in several Latin American countries, and foresaw a future for its use in teaching foreigners preparing for American citizenship. “Let us go into this together,” he declared. Again, paying special attention to the academic world, he asserted: “Let us go forward in malice to none and good will to all. ...The empires of the future are the empires of the mind.”

Nearing his conclusion, Churchill looked back to the failures of the League of Nations and touched on other systems of world security under public discussion. “Nothing,” he declared, “will work soundly or for long without the united effort of the British and American peoples. If we are together nothing is impossible. If we are divided all will fail. I therefore preach continually the doctrine of the fraternal association of our two peoples, not for any purpose of gaining invidious material advantages for either of them, not for territorial aggrandizement or the vain pomp of earthly domination, but for the sake of service to mankind and for the honour that comes to those who faithfully serve great causes.”

He closed with a mighty peroration:

Here let me say how proud we ought to be, young and old alike, to live in this tremendous, thrilling, formative epoch in the human story, and how fortunate it was for the world that when these great trials came upon it there was a generation that terror could not conquer and brutal violence could not enslave.... Let all who are here remember that we are on the stage of history, and that whatever our station may be, and whatever part we have to play, great or small, our conduct is liable to be scrutinized not only by history but by our own descendants.

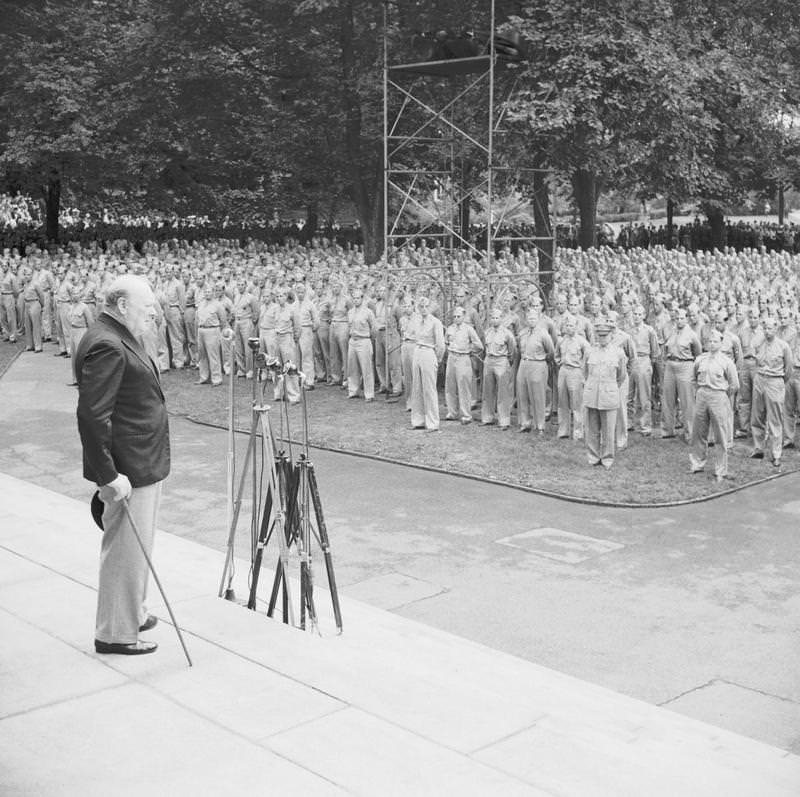

Thunderous applause ensued. Churchill himself was beaming. Ushered by President Conant, he walked to Tercentenary Theatre where, from the south porch of Memorial Church, Conant introduced him to more than 7,000 uniformed officers-in-training lined up in parade formation.

Photograph courtesy of The United Kingdom Government/Public Domain

The PM responded with a four-minute, extemporaneous pep talk, punctuating his points by the constant beat of his cane on the platform. He stressed the utmost value of the intensive military studies being given to these young men and women as they prepared for war on land, sea, and in the air. He said that although the final outcome of the war was no longer in doubt, he foresaw that many of “the heaviest sacrifices in blood and life” that still lay ahead. The forthcoming invasion of Normandy had been discussed at the Quebec Conference the month before, and he knew that many of the men and women standing in front of him would not return alive from one of the bloodiest encounters in the European war.

••••••••••••

The total time Churchill spent at Harvard was about four and a half hours. But he gave to Harvard one of the most important and remembered moments in all of its nearly four centuries of history. Thinking back to the understanding of great figures in history, Ralph Waldo Emerson, A.B. 1821, LL.D. ’86, once wrote, “We mark with light in the memory” our meetings with “great souls that make our own souls wiser.” Churchill’s visit to Harvard in September 1943 is one of those moments to recall as if “with light in the memory.”