The most political case of the indelibly political Supreme Court term that ended in June was about the travel ban President Donald J. Trump imposed last September. It banned almost all travel to the United States from seven countries where more than 135 million people were covered by the ban. More than 90 percent of the citizens in five of the countries were Muslim. As the state of Hawaii said in its brief about the case called Trump v. Hawaii, this element of the ban violated the Constitution’s “bedrock command that the Government may not take actions for the purpose of excluding members of a particular faith.”

The Trump administration claimed the ban was “religion-neutral,” with restrictions “expressly based on the President’s national-security and foreign-policy judgments.” A prime point of contention was the stream of statements Trump had made stressing his aim of barring Muslims from the United States. When the Court heard oral argument in the case, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. ’76, J.D. ’79, assumed Trump had made the statements with that purpose. Roberts asked Hawaii’s lawyer: “If tomorrow he issues a proclamation saying he’s disavowing all those statements, then the next day he can reenter this proclamation” and “your discrimination argument would not be applicable?” The lawyer said, “Absolutely.”

Solicitor General Noel J. Francisco, representing the administration, asserted in rebuttal that there was nothing to disavow: “Well, the President has made crystal clear on September 25th that he had no intention of imposing the Muslim ban.” The following day in Slate, Joshua A. Geltzer, a visiting professor of law at Georgetown University, explained why that assertion was inaccurate. “Here’s the problem. No such thing seems to have happened on September 25th.” He went on, “Time and again, Trump and the White House have said the opposite of what Francisco represented to the court on Wednesday.”

A few days later, Francisco sent a letter to the Court saying that, when he referred to a statement by the president on September 25, he meant January 25, when Trump said a previous version of the travel ban addressed “countries that have tremendous terror,” but was “not a Muslim ban.” The next day in Slate, Geltzer called Francisco on that claim, too. The president’s full statement on January 25 made plain that, to Trump, his administration’s ban was a Muslim ban, but narrower than the absolute one he promised—“the Muslim ban,” Francisco called it, with “the” implying absoluteness. And to Trump, the narrowing was regrettable. Francisco’s argument to the justices, Geltzer wrote, was “dangerously misleading.”

To close observers of the Court, Geltzer was making a weighty point about the solicitor general: the S.G., as the lawyer in the post is known, had put the interests of the Trump administration ahead of those of the Court and the justices should be wary of his assertions in this matter. By fudging facts—about the travel ban itself, as well as about the president’s purpose in imposing it—to fit the view of the law he was trying to persuade the justices to take, Francisco had violated the scrupulous standard of candor about the facts and the law that S.G.s, in Republican and Democratic administrations alike, have repeatedly said they must honor.

In June, when the Court upheld the ban by 5-4, there was no apparent penalty for this duplicity. For the conservative majority, Roberts wrote that the law in question “grants the President broad discretion to suspend the entry of aliens into the United States” and President Trump “lawfully exercised that discretion.” In reviewing the president’s anti-Muslim statements, the Court had to consider “not only the statements of a particular President, but also the authority of the Presidency itself.” He stressed, quoting an old opinion, “For more than a century, this Court has recognized that the admission and exclusion of foreign nationals is a ‘fundamental sovereign attribute exercised by the Government’s political departments largely immune from judicial control.’”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote a piercing dissent. She said the ban is “motivated by hostility and animus toward the Muslim faith,” that it’s “inexplicable by anything but animus,” and that it “now masquerades behind a façade of national security concerns.” She closed, “Our Constitution demands, and our country deserves, a Judiciary willing to hold the coordinate branches to account when they defy our most sacred legal commitments.”

It was the president who needed to be held to account. Martha Minow, Harvard’s 300th Anniversary University Professor, and Robert Post ’69, Ph.D. ’80, a Yale Law School professor, wrote that Trump has come “perilously close to characterizing the law as simply one more enemy to be smashed into submission.” The S.G.’s fudging drew attention because it raised the disturbing prospect of the S.G. sacrificing the integrity of the office as part of that smashing.

But the Court’s seeming indifference to the S.G.’s misrepresentation reflects another change in practices, under way for two generations and a contributor to major shifts in the S.G.’s role. With the Court divided ideologically along partisan lines for the first time in history, between conservatives nominated by Republicans and liberals by Democrats (a division deepened by the retirement of the sometimes-libertarian Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, LL.B. ’61, since Brett Kavanaugh, the Trump nominee to replace him, is likely to be more conservative), the S.G.—no matter the administration—has become more political. How did this esteemed post, which the Court long regarded as the keel keeping the government balanced when it threatened to heel too far to the left or right, come to contribute to forceful tacks one way or the other, to the Court’s seeming indifference?

Archibald Cox, Solicitor General of the United States in the Kennedy administration

Photograph by PhotoQuest/Getty Images

A comparison of the divergent approaches of Harvard Law School’s late Archibald Cox ’34, LL.B. ’37, LL.D. ’75, as S.G. in the 1960s and Charles Fried in the post in the 1980s (he is the Beneficial professor of law) illuminates these important changes. (Eight of the nation’s 48 S.G.s went to HLS, have taught there, or both, including Justice Elena Kagan, J.D. ’86, the only female S.G.) The changes matter because the solicitor general remains, by a wide margin, the most frequent and influential advocate before the Supreme Court. The changes reflect the changed nature of the Court, which is at the center of American life.

Law and Policy Fused

The S.G. is traditionally called the “tenth justice,” though it’s obvious the Court has only nine justices. The moniker is a shorthand for what’s been inspiring about the position: Thurgood Marshall, then an actual justice and a former S.G., called it “the best job I’ve ever had, bar none!” The S.G. is the only national public official, including the Supreme Court justices, required by statute to be “learned in the law.” The job is to represent the executive branch at the Court and to decide which cases it appeals to the Court and to the federal appeals courts, yet the S.G. has an office at the Supreme Court as well as at the Justice Department.

Those offices in different branches of government represent what Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., LL.M. ’32, called the S.G.’s “dual responsibility”—as an advocate for the president yet also as a counselor to the Court, expected to help the justices reach the right result in the law.

S.G.s have long engaged in practices that confound the ideal of zealous advocacy at the heart of the adversary system. They have confessed error in cases they thought the government won unjustly and recommended that the Supreme Court overturn the decision. They have refused to argue the merits of cases in which they thought a victory for the government would be a miscarriage of justice, or even to sign the government’s briefs—or they have signed the briefs, but signaled their disapproval in a footnote, known as tying a tin can: that tiny notation noisily clangs, stressing that the brief presented is not the S.G.’s.

The 1978 Bakke case about affirmative action in university admissions was one of the most contested of the past half-century. When a white engineer sued a University of California medical school for reserving 16 of the 100 places in its entering class for minorities, claiming that deprived him of equal protection of the law, President Jimmy Carter, pressured by cabinet officers, directed his S.G. to advocate strongly for affirmative action. The Court’s resolution of the case—in favor of affirmative action but against reserving those places at Davis—was equivocal. The Justice Department’s response to the controversy was clear-cut.

Its Office of Legal Counsel, in 1977, laid out the argument for the independence of the S.G.’s office. “The short of the matter is that under our law,” a memorandum said, “the Attorney General has the power and the right to ‘conduct and argue’ the Government’s case in any court of the United States” and the S.G. worked for the A.G. But “the tradition of the ‘independent’ Solicitor General is a wise tradition,” the memo went on, because the A.G.’s political duties might “cloud a clear vision of what the law requires.” Legal judgments, the S.G. should make. Policy judgments, the A.G. should. “But the Attorney General and the President should trust the judgment of the Solicitor General not only in determining questions of law but also in distinguishing between questions of law and questions of policy.”

The memo’s premise was that, in most instances, law and policy—politics—could be distinguished. Since 1977, however, that distinction has been all but obliterated in the most important cases before the Supreme Court. In them, the Court is a political institution, as many scholars have documented and most Americans believe. In 2015, the Pew Research Center found that 70 percent, spanning partisan and demographic groups, “say that in deciding cases, the justices of the Supreme Court ‘are often influenced by their own political views.’”

The justices are products of politics. That’s unmistakable in the selection processes of presidents and the confirmation clashes of the Senate. Justices’ rulings are often also products of their ideologies—about how the Court should allocate power, opportunity, and other elements of society. Under the traditional ideal, judges reached results by applying legal rules independent of political pressures. A classic example is the many federal-trial-court orders calling for desegregation of public schools in the South after Brown v. Board of Education held that separate-but-equal education violated the Constitution, despite furious opposition to racial integration. The contemporary reality in the most important cases is that the justices apply rules in ways that are products of politics.

Since 1969, three conservative chief justices, appointed by Republican presidents, have led an increasingly conservative Court. It’s about to enter its fiftieth year as what the legal scholar Lee Epstein called the Republican Court, because of the link between the dominance of Republican-picked justices and the Court’s conservative emphasis. In the recent term, of the 14 ideological cases decided by 5-4, 100 percent were conservative victories. The political war over Kennedy’s replacement—the fifteenth justice nominated by a Republican president of the Court’s last 19, including the chiefs—punctuates the point. The memo about the S.G.’s role reflected the traditional ideal. The ideal gave way to the new political reality.

Pamphleteer General

The conflicting approaches of Archibald Cox and Charles Fried as S.G. showcase the difference between ideal and reality. Cox, a crew-cut patrician, was S.G. for four years in the Kennedy administration. Two decades later, Fried, an urbane cosmopolitan, filled the post for four years in the Reagan administration. As HLS professors on leave to serve as S.G. who prided themselves on their pedagogy—Cox was on the faculty from 1945 until 1984, with stints away for public service; Fried has been on the faculty since 1961, also with stints of service—each was emphatic about why he took his approach.

Cox’s grew out of his adherence as a liberal to judicial restraint—the philosophy of judicial deference to the executive and legislative, or political, branches—which was embraced by his mentors Felix Frankfurter, LL.B. 1906, LL.D. ’56 (an HLS professor who became a justice), and Learned Hand, A.B. 1893, A.M. ’94, LL.B. ’96, LL.D. ’39 (the renowned federal-appeals-court judge whom Cox clerked for in Manhattan), as liberals whose views were formed in a conservative Court era. Fried’s approach was reinforced by his training as a legal philosopher focused on the values underlying laws and on how laws empower or encumber those values, and as a liberty-embracing, autonomy-promoting conservative whose views were formed in a liberal Court era.

Their views were distilled in contrasting stances—Cox’s cautious, Fried’s aggressive—about when the S.G.’s office should file friend-of-the-court, or amicus-curiae, briefs at the Court. (These are filed on behalf of organizations or people not in a case as a party—initially as plaintiffs or defendants, later either petitioning the justices to hear it on appeal or responding on the other side—who have information or insight that they think the Court could benefit from, since specific cases raise general questions and the parties don’t always address them.) The growth in such filings is a proxy for the transformation of the Court since World War II: from a relatively weak institution and guardian of federalism into a relatively strong branch of government and champion of nationalism, in the sense of developing national law so all individuals would be treated equally.

Until Cox became S.G., the government rarely filed amicus briefs: it was unusual for anyone to file them in Supreme Court cases. In the 1960s, however, in what Cox called “a new period in our constitutional development” under the Warren Court, the S.G.’s office began to appear regularly as an amicus at the Court as such filings in general soared. Between 1961 and 1966, about 20 percent of the government’s appearances at the Court were as amicus. (The remaining 80 percent continued to be as a party in a lawsuit, either as the petitioner who brought the case or as the respondent.) Samuel Krislov wrote in the Yale Law Journal, in 1963, that “the amicus is no longer a neutral amorphous embodiment of justice, but an active participant in the interest group struggle” and “has moved from neutrality to partisanship, from friendship to advocacy.” The amicus brief became a tool of political lobbying, for pursuing social and legal change as the Court increasingly sought to resolve in law major disputes in society.

In this period of expansion for the Court, Cox’s caution about filing amicus briefs stood out. In 1985, when I interviewed him for my 1987 book, The Tenth Justice: The Solicitor General and the Rule of Law, he said, “We had the feeling when we filed an amicus brief that we had an even stricter responsibility to the guardians of the law than we normally did. We couldn’t just take a strong position on behalf of a state, for example. We had to be especially careful about what we said the law was or should be.”

In deciding whether to file an amicus brief, Cox was punctilious in meeting standards he chose: Was the question important to constitutional law? Would the answer affect a lot of people? Could a government brief really help the Court? Was the government’s interest “direct”—would it be directly affected by the case’s outcome?

In 1962, by 6-2 in Baker v. Carr, the Court ruled that it had the authority to decide cases about reapportionment of legislative districts. (Earl Warren called it the Court’s most important ruling while he was chief justice.) Cox’s predecessor as S.G. had decided to enter the case as an amicus on behalf of fairer apportionment, but Cox was not sure he should make an oral argument. As recently as 1946, the Court had ruled that reapportionment was “a political question” for the legislature to decide. When Cox did make the oral argument, Ames professor of law emeritus Philip B. Heymann (an assistant to Cox at the time) told me: “Archie stood up and said, ‘It is respectable and nothing terrible will happen if you take on reapportionment.’…He wrestled with Baker v. Carr a long time, and it’s one of those cases where the lawyer made all the difference.”

Between 1959 and 1986, the legal scholar Rebecca Mae Salokar found, the party the S.G. supported as an amicus won 72 percent of the time—and, in the past three decades, that rate remained the same. The score for Cox was 89.4 percent.

To Fried, the explosion of law under the Warren Court led to enormous costs for the United States, in the growth of litigation, violent crime, and what he saw as perversion of the American system: in a speech in 1985, he said that “educational opportunities, housing, judgeships—all the good things were being handed out, not on merit, but by a racial and ethnic and religious and gender spoils system.” At a seminar that year, he explained why this view led him to reject key Warren precedents: “Judicial restraint”—including adherence to precedent—“may require judges to be faithful to a lot of things which, in the abstract, don’t deserve fidelity.” Fried defined the government interest broadly so he could enter any case where the Reagan administration, viewing amicus briefs as tools of change, wanted to put itself on record.

In Fried’s first year as S.G., the share of the government’s cases in which he filed an amicus brief climbed to 41 percent. Throughout the Reagan years, the S.G.’s office took part in 62 percent of the cases that the Court decided on the merits—on the basis of the law and the facts—rather than on technical or procedural grounds. It was involved as a party in 61 percent, in 39 percent as an amicus, almost twice the rate as under Cox.

For Fried, the equivalent of Baker was the Thornburgh abortion case. In 1973, Roe v. Wade had established, 7-2, the constitutional right to abortion. In 1983, the Court had affirmed that right, 6-3, saying “the doctrine of stare decisis”—following precedent—“demands respect in a society governed by the rule of law.” In 1986 in Thornburgh, by 5-4, the Court reaffirmed the right, with the majority correcting a key assertion in the government’s brief, which said that lower federal courts had showed “unabashed hostility” to state attempts to regulate abortion; the majority opinion said it was the states that showed hostility to the right to abortion.

Where Cox had hesitated about Baker, Fried was decisive in Thornburgh. Cox felt constrained by what courts said the law was. Fried didn’t. Stirring immense controversy, his brief called for striking down the right to abortion only three years after the Court affirmed it, because “the textual, doctrinal, and historical basis for Roe v. Wade is so far flawed” and it “is a source of such instability in the law that this Court should reconsider that decision and on reconsideration abandon it.”

In 2009, in The Journal of Politics, the political scientist Patrick C. Wohlfarth wrote that Fried’s aggressive approach had ill effects. “Generally speaking,” he said, “a solicitor general who politicizes the office acts as a forceful advocate for executive policy at the expense of assisting the Court.” The price Fried paid, Wohlfarth showed in a statistical analysis, was a decline of 15 percentage points in his success rate compared to his Republican predecessor. Importantly, the analysis showed that other S.G.s paid a similar price: “the Court’s perceptions of the S.G.’s political bias” exerted “a systematic, negative impact on the office’s credibility.”

Yet seen in longer perspective, the contrast between Fried’s record and Cox’s is less significant than this: Cox started a trend that Fried accelerated. Most S.G.s since have continued to increase it. In the Obama administration, the S.G.’s office took part in 82 percent of the merits cases the Court decided. Among them, it took part in 43 percent as a party and 57 percent as an amicus—almost three times Cox’s rate as an amicus and almost 50 percent higher than Fried’s.

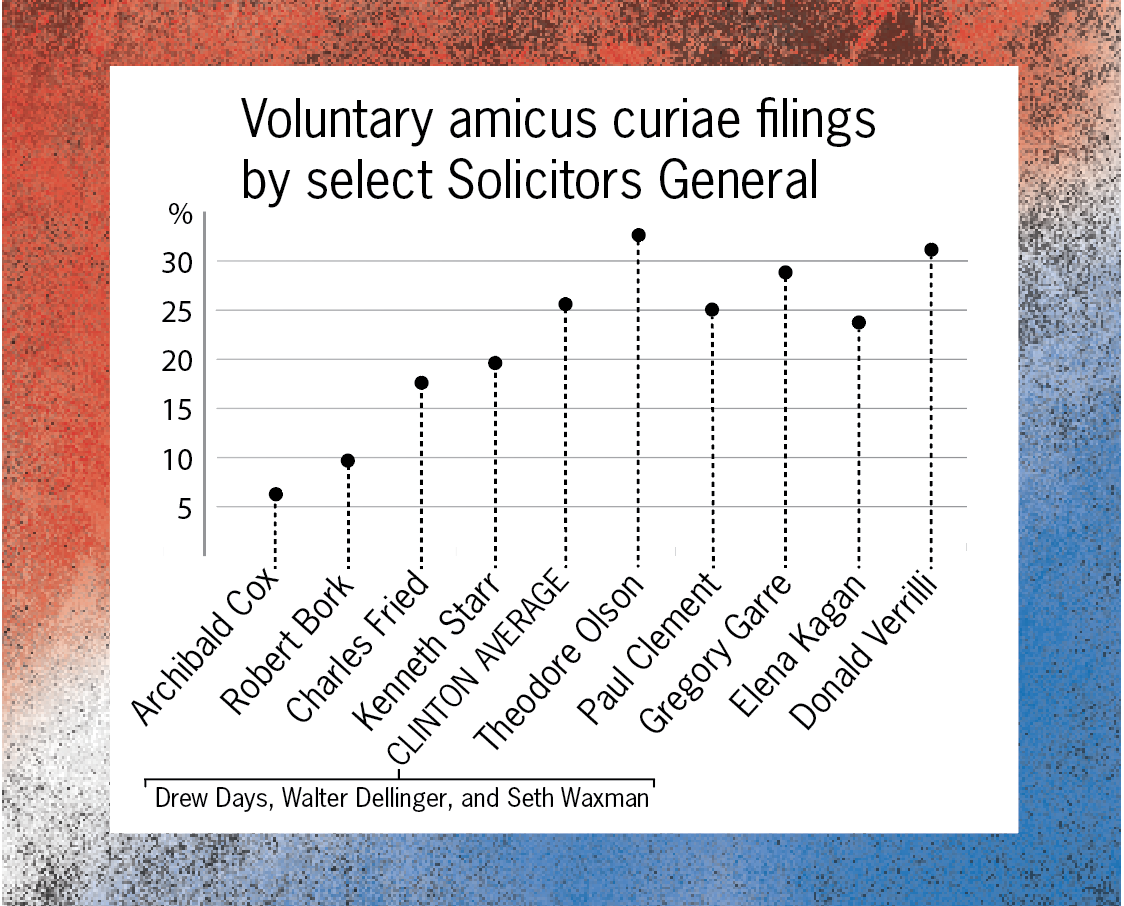

Wohlfarth’s article was based on an analysis of “all voluntary amici curiae filed by the solicitor general’s office during Supreme Court terms 1961–2003”—under every S.G. from Cox through Theodore B. Olson for President George W. Bush. He omitted amicus briefs the S.G. filed at the request of the Court, so the data reflect only cases where the S.G. chose to file and was especially likely to present a view favored by his administration—to make a political statement. When the level of “S.G. politicization” climbed from the low end to the high, Wohlfarth found that the Court’s support for the S.G.’s position fell from 87 percent to 60 percent.

He shared the data from the ’61 through ’03 terms and brought it current through the 2014 term, near the end of Obama S.G. Donald B. Verrilli Jr.’s five-year tenure. In the past half-century, the share of voluntary amicus briefs has increased almost fivefold.

When Fried returned to Harvard, he published an instructive book in 1991 called Order and Law about his time as S.G. that put his service in a more scholarly perspective. He shared what he called Reagan’s “gut-level dislike for the pretensions of government in general.” The “Reagan Revolution” challenged those pretensions. They included, among others, “an exaggerated faith in bureaucracy and government expertise,” especially the federal courts as “major bureaucratic actors, enthusiastically, self-consciously enlisting in the movement to substitute the judgments and values of the nonproductive sector of society—lawyers, judges, bureaucrats, politicians—for the self-determination of the entrepreneurs and workers who create wealth.”

To Fried, the 20 or so career lawyers in the S.G.’s office carried on the Cox approach:

In an important sense government is law. This is an ideal that entails a kind of regularity, objectivity, and professional technique apart from—maybe even above—politics. These brilliant and hardworking lawyers had signed up in the service of that ideal. They had not enlisted in the Reagan Revolution. What they consistently failed to see was the extent to which the traditions and precedents of the office had become clogged with commitments and assumptions that were in fact political. I was constantly being told that I should not intervene in cases where all I had to add was a philosophical statement about how the law should come out. I was supposed to represent the interest of “government” in general—that is, the ability of government to go about its work, whatever it may be, as freely as possible. The political bias of this attitude was obscured because since the 1930s the prerogatives of the federal government had been overwhelmingly involved in furtherance of a liberal, regulatory agenda.

Fried wrote, “In a real sense the Solicitor General is responsible for the government’s legal theories, its legal philosophy.”

He told me recently, referring to those passages, “What those statements leave out is the continuing validity of the view of law as ‘regularity, objectivity, and professional technique apart from—maybe even above—politics.’ I certainly believe that now and I hope I believed it then.” In other words, it was important to challenge the political commitments and assumptions embedded in the traditions and precedents of the office, but to do so as respectfully as career lawyers articulated them.

Order and Law laid out what has more or less become the norm for S.G.s in every administration since, and why Rebecca Mae Salokar, in her S.G. study, concluded, “The Solicitor General of the United States is an important political actor.”

The first Reagan S.G., Rex E. Lee, whom Fried replaced, was a conservative worn down by pressure from other political appointees to take aggressively conservative positions in social-agenda cases—to call for striking down the right to abortion after the Court signaled it wouldn’t, restrict affirmative action more than the Court said it was ready to, and allow spoken religious prayer in public schools after the Court compromised at allowing only silent prayer, for example. He took conservative positions in the cases, but said he felt constrained by the law’s “careful modulations.”

When Lee left office after four years, in 1985, he told me in an interview, “There has been this notion that my job is to press the administration’s policies at every turn and announce true conservative principles through the pages of my briefs. It is not. I’m the solicitor general, not the pamphleteer general.” Lee’s phrase conveyed the essence of the difference between the traditional ideal that Cox championed and the political reality that Fried explained and that now prevails. By his time, in key cases, the S.G. had become the pamphleteer general—the chief articulator of the administration’s legal philosophy.

The Counselor’s Role Reduced

After his S.G. service, Lee helped the Washington, D.C., office of a national law firm develop a Supreme Court practice. That was the start of a modern Supreme Court bar outside the S.G.’s office. By the 1980s, the emergence of the global economy and the increase in the size of business deals transformed the market for corporate legal services. As firms mushroomed to provide the gamut of them, a Supreme Court practice embellished their offerings, especially with the prestige of a former S.G. leading it. Of Lee’s 10 successors (excluding the current S.G.), only one hasn’t formally led or joined a private practice or contributed to one: Justice Kagan. Aibel professor of law Richard Lazarus worked as a young lawyer in the S.G.’s office under Fried. A decade ago, in an article titled “Advocacy Matters Before and Within the Supreme Court,” he wrote that “what has gone wholly unrecognized by all, including legal scholars,” was how this emergence of a Supreme Court bar of elite attorneys was “quietly transforming the Court and the nation’s laws.”

The new Supreme Court bar quickly became successful, influencing the Court’s docket and winning for its clients. In the Court’s 1980 term, expert counsel outside the S.G.’s office filed only six successful Court petitions, a 5.7 percent success rate. By the 2006 term, when Lazarus was writing, the tally was 28 petitions and 44 percent. The new bar, he spotlighted, was shifting the Court’s docket “to topics more responsive to the concerns of private business” by changing the justices’ priorities and interests. The bar has successfully persuaded the Court to take many business cases and helped make the Roberts Court strongly pro-business.

Lazarus didn’t pay a lot of attention to how the rise of this group affected the S.G.’s office, beyond the new opportunity for lawyers there to move to prestigious, high-paying jobs while continuing to practice before the Court. But the bar’s docket-shaping contributed to the evolution in the S.G.’s role, too. The S.G.’s office continued to decide which government cases it wanted to take to the Court or to keep from getting there, but its overall influence on the Court’s docket shrank considerably. It has also appeared much less often as a petitioner (the party that lost in a lower court and is asking the Court to reverse that ruling) than as a respondent (the party that won and now must defend that victory). The respondent is much more likely to lose. These shifts were intensified by a steep drop in the docket’s size, from an average of more than 150 merits cases a year in the early 1980s to 74 in the past five years.

Charles Fried, Solicitor General of the United States in the Reagan administration

Photograph by Emily Berl/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

The S.G.’s role is strikingly different than when Cox filled it two generations ago. As the balance between the S.G.’s advocacy as a party in a case and as an amicus has shifted to the latter, the balance between his character as a counselor to the Court and as an advocate for the executive branch has shifted, too. The S.G. retains a counseling function. The focus of career lawyers in the S.G.’s office on the long-term interests of the law, a former S.G. said, is “a very strong force within the office” and “you’d be risking a calamitous tenure as S.G. if you didn’t pay significant heed to that perspective.” But the S.G.’s role is measurably more political. Except in rare circumstances, the S.G. doesn’t hesitate to enter any case with a significant impact on public policy. With rare exceptions, the Supreme Court seems to expect the S.G.’s office to weigh in.

This former S.G. said, “The change in expectations has been so great that the action that would raise eyebrows and create the risk of negative inferences that might be unwarranted is when the United States doesn’t participate.” He went on, “This expectation on the part of the Court that this is a difficult, sensitive matter and we want to hear what the United States has to say about it means that the S.G. is going to be in the middle of something that’s highly politicized.”

The challenge to what’s left of the S.G.’s role as counselor to the Court now rarely arises from threats to its “independence” by other political appointees. S.G.s are superb lawyers, but they are carefully vetted. The legal philosophy each one brings to the office is well known.

In their 2012 volume The Solicitor General and the United States Supreme Court, the political scientists Ryan C. Black and Ryan J. Owens used data from the 1946 through the 2010 Court terms, and a statistical technique called matching, to compare the S.G.’s influence on the Court in general—in setting its docket, in how it comes out in cases, in the opinions justices write, and even in how they treat precedent—and how these elements differ when the S.G. isn’t involved. They found that the S.G.’s office “influences every major aspect of the Court’s decision-making process,” because of “its objectivity and professionalism.”

Their analysis is not historical and doesn’t concentrate on the changes in influence in the past generation, as Jacqueline Bell and Cristina Violante did last October in Law360. They found a startling decline in the S.G.’s win rate in the past generation: “The SG’s office fell short of its 30-year average win rate in 8 of the past 10 terms.”

One factor was the success of the Supreme Court bar. The S.G. now has excellent competition. Another was politics. Some of the decline, they wrote, was “the natural result of a liberal solicitor general representing a liberal administration tangling with a court that, by some measures, is one of the most conservative in decades.”

The overall decline also masked big exceptions to that pattern, like the 2014 term when the Court decided same-sex marriage is a fundamental right. The term ended so well for Donald Verrilli that former acting S.G. Walter Dellinger gushed in Slate, “This may be the greatest Supreme Court term any solicitor general has ever had.”

Black’s and Owen’s analysis doesn’t take account of the increase in voluntary amicus filings since the end of the 2003 term when Patrick Wohlfarth’s analysis ended. The increased politicization of the S.G.’s filings and the continued high win rate of parties the S.G. supported as an amicus bolsters the view that, while the S.G. has become more political, the political Court has come to discount that.

Course Reversed

When the Senate approved Noel Francisco as S.G. last September, the headline of the Courthouse News Service was “Senate OKs Federalist Society Nominee for US Solicitor General.” The society is the organization of conservative lawyers started in the Reagan era that grooms and screens conservative candidates for judgeships and executive-branch positions—the “single outside group,” Linda Greenhouse ’68 wrote in The New York Times, from which Trump accepted “a predigested, preapproved list of potential nominees” from which to make his recent Court pick. Francisco’s ideological profile made it unsurprising that his Senate confirmation vote was close—50 to 47—and completely along party lines.

Last summer, Adam Liptak wrote in the Times about the Trump administration’s reversals of Obama administration positions in major cases about rights of workers and about rules for cleaning up voter rolls: “The decisions to change course cannot have been made lightly, as lawyers in the solicitor general’s office, the elite unit of the Justice Department that represents the federal government in the Supreme Court, know that switching sides comes at a cost to the office’s prized reputation for continuity, credibility and independence.” The Trump administration ended up reversing positions of the Obama administration in four major Court cases.

In 1992, Rebecca Mae Salokar said she had found only one example of this kind of shift between 1959 and 1989. Griffin Bell, attorney general in the Carter administration when that happened, wrote in his memoir that it was almost an axiom that a reversal in a case would be seen as the result of a new “administration imposing its policy views on the Justice Department despite the department’s contrary judgment of the law.”

Near the start of Francisco’s argument at the Court in the voter-rolls case, Justice Sotomayor interrupted to address that reversal. She said, “General, could you tell me, there’s a 24-year history of solicitor generals of both political parties under presidents of both political parties who have taken a position contrary to yours.” She went on, “How did the solicitor general’s office change its mind?”

To carry out the law’s prohibition against removing anyone from the rolls because he has not voted, Francisco replied, those predecessors had read into the National Voter Registration Act a requirement that a state can start removing someone from its voter rolls only if it has reliable evidence that he moved away and is no longer a resident. The Trump S.G.’s office abandoned that reading because the requirement is “found nowhere in the text” of the law.

He advocated upholding an Ohio law that let the state do what the federal law banned, by beginning the purging of people from the rolls only because they had not voted. The heart of that process was a lame effort to confirm that someone had moved from one state to another. Ohio could remove such individuals from the rolls after it sent them a notice to which they didn’t respond, and after they didn’t vote for four years—even if they hadn’t received the notice and remained eligible to vote.

In 2012, Ohio sent notices to about one-fifth of its registered voters—about 1.5 million people. About 4 percent returned their cards to confirm they had moved—the same percentage for Americans who move outside their county in an average year. About 15 percent wrote back to say they had not moved. But more than 80 percent didn’t respond. The law canceled the voter registration of thousands of eligible voters—144,000 people in Ohio’s three largest counties, at twice the rate in Democratic neighborhoods as in Republican ones.

The purge program fit a centuries-old pattern, in the words of The Right to Vote by Alexander Keyssar, Stirling professor of history and social policy, of “keeping African-American, working-class, immigrant, and poor voters from the polls” (see “Voter Suppression Returns,” July-August 2012, page 28). The S.G.’s shift in position made him an advocate for one of the most partisan pursuits in American politics. The quest was said to be based on concern about voters’ intentional corruption of the electoral process. That “problem” is virtually nonexistent in the United States.

When the Court upheld the program by 5-4, in June, with the conservatives again in the majority in a patently political decision, not even a dissent from Sotomayor mentioned the S.G.’s change of position. The reputation of the post appeared intact in its reshaped role. Including all four cases involving major reversals, Francisco’s conservative advocacy in his first term as S.G. was decidedly successful before the conservative Court.