The University’s financial report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2018, published today, reflects results from before Lawrence S. Bacow became president, on July 1, but depicts the conditions and resources he and his deans now have to work with—including a fifth consecutive budget surplus, nearly $200 million—during a period of continued U.S. economic growth and at the end of the $9.62-billion Harvard Campaign. The report also includes an annual message from Harvard Management Company (HMC) chief executive N.P. Narvekar, in which he unexpectedly shed considerably more light on the composition of the endowment—the first gloss on the notably sparse report of results (a 10 percent investment return during fiscal 2018) released September 28—and updated his progress in completely overhauling the investment process to boost returns (see the section on the endowment below).

Highlights of the University’s fiscal year:

- Revenue increased nearly $217 million to about $5.2 billion (growth of 4.3 percent): nearly on pace with the 4.6 percent growth in fiscal 2017, despite sharp restraints on distributions from the endowment—the University’s largest source of revenue (see discussion below).

- Expenses rose, too, by $134 million to just more than $5 billion (2.7 percent)—continuing a moderating trend (up 3.9 percent in fiscal 2017 and 5.3 percent in the prior year). Although some one-time factors affected the results, it appears that deans, expecting constrained endowment distributions, reined in their spending suitably.

- The result was an operating surplus of more than $196 million—contradicting, in all the ways that make financial officers happy, the message sent last year that the $114-million surplus reported then might well be the “high-water mark for the foreseeable future.” This was the fifth consecutive surplus, meaning that the schools have continually accumulated resources (which may come in handy as reserve funds when conditions are less favorable—or may be applied to their teaching and research missions and new ventures in coming semesters).

Bacow’s introductory letter was short and sweet: principally, a thank-you note to his predecessor, Drew Gilpin Faust, and to the donors whose past and recent benefactions have powered the University forward.

Thomas J. Hollister

Paige Brown, Courtesy Tufts Medical Center

Similarly, vice president for finance Thomas J. Hollister, Harvard’s chief financial officer, and treasurer Paul J. Finnegan (a member of the Corporation and chair of HMC’s board), were relatively restrained in their letter. In light of Harvard’s accumulating surpluses, they reiterated their squirrel’s-eye perspective on the wisdom of storing up acorns for harder times to come (in the economy and the economics of higher education), but perhaps with less dire urgency than they mustered last year.

In passing, they note, but do not comment on, a shift in the University’s sources of revenue for the year: endowment distributions, 35 percent (down one percentage point); net tuition and other sources of revenue from students, 22 percent (up one point); and sponsored research support, 18 percent; current-use gifts, 9 percent; and other, 17 percent (all substantially unchanged). And they single out the pending tax on endowment investment income, enacted last December, which may cost Harvard $40 million to $50 million annually, equal to about 25 percent of the fiscal 2018 budget for undergraduate financial-aid grants. (Given uncertainties about implementation, and the timing of the University’s tax filings, the financial statements make no provision for paying the levy in fiscal 2018. The law’s operations, when clarified, would begin to take effect for Harvard as of this past July 1.)

Before dissecting the year in detail, HMC’s report merits attention.

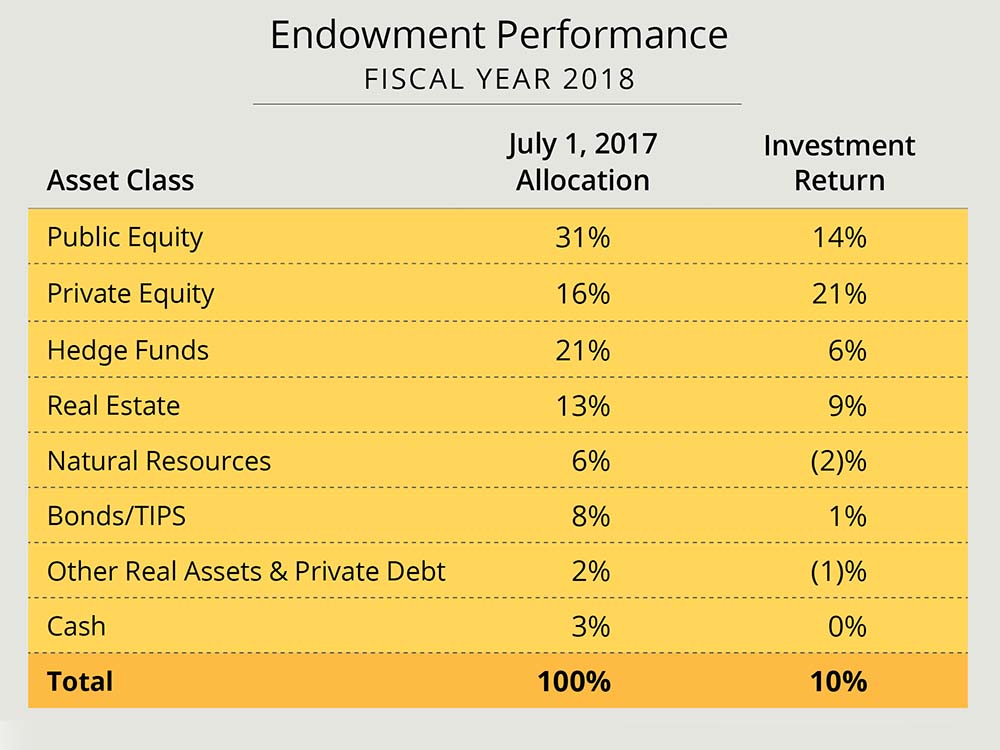

The Endowment: The Curtain Pulled Back

In his report on the endowment, Narvekar provided some of the asset-class information HMC had published annually before his arrival in late 2016. Notably, although he emphasizes the unified, generalist way HMC now assesses risk and makes investment decisions for the endowment as a whole (in contrast to the prior, siloed, by-asset-class model he has discontinued), he did provide rough allocations and returns by category, as shown here. (The assets are reported in such categories in the footnotes to the University’s annual financial report.)

Harvard Management Company data, from Harvard University Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2018

For students of the subject, the fiscal 2016 allocation (from shortly before Narvekar arrived) was 29 percent public equities (spread across domestic, foreign, and emerging-market categories); 20 percent private equity; 14 percent “absolute return” (hedge funds); 14.5 percent real estate; 10 percent natural resources; and 12.5 percent various classes of bonds.

Narvekar disclosed last year that HMC had taken significant losses on the natural-resources portfolio, disposing of assets and marking others down. It also sold various real-estate and private-equity holdings then—and continued to do so in fiscal 2018. A review of this year’s financial-report footnotes reveals within the general investment account (which includes the endowment) an increased appetite for foreign, global, and emerging-market stocks, compared to the end of fiscal 2017; decreased holdings of U.S. and high-yield bonds (perhaps not surprising with rising domestic interest rates); and a multibillion-dollar increase in hedge-fund investments and commitments to invest in the future, plus a lesser increase in private-equity assets. Natural resources and real estate both were reduced over the course of the year.

Assessing the results, Narvekar wrote about two issues: “First, there are certain parts of the portfolio that need work,” which is under way (notably: downsizing the natural-resources portfolio and managing the remaining assets; and, presumably, repositioning the cohort of hedge-fund managers). “Second, looking beyond the returns of individual asset classes, asset allocation—or risk level—was the dominant factor in the overall returns. In general, the higher the risk level, the higher the return.”

Continuing his taut narrative, Narvekar observed that “as sophisticated investors well know, there are very limited conclusions that we can draw from a single year of either manager performance or asset allocation.” (Perhaps given the discontinuities associated with the wholesale transformation under way at HMC, he does not provide annualized returns for three, five, or 10 years—the traditional measurement for performance over time.) Thus, “Had this past year’s return been significantly higher or lower, it still would not be reflective of the work we are undertaking, nor change the path we are pursuing. This is a reality that will apply to the remaining years of our transition as well.” (The returns of many peer institutions that use the management approach HMC is now installing were higher than Harvard’s fiscal 10 percent return; their risk profiles and return objectives differ, of course.)

In a refinement, or perhaps a restatement, of his description of the duration of that transition, Narvekar wrote that “the significant changes we are undertaking require a five-year timeframe to reposition the organization and portfolio”—a message he has underscored continuously. But he added a phrase about “subsequent strong performance,” for those who may have missed the subtlety. That is to say, remaking HMC and activating its new investment disciplines, refining its risk framework (at least a two-year collaboration with HMC’s board and the University, beginning soon); reestablishing relationships with superior external fund managers; and getting them money to invest, are all encompassed within that five-year transition—after which harvesting the presumably superior results should show up. That is the nature of investing appropriately in long-term, illiquid assets, where those higher risks and returns reside over time. Or to sum matters up in his words:

[W] are in the midst of a five-year transition. Developing our investment team into generalists, building the systems to support our investment framework, and repositioning the portfolio—reducing exposure to certain illiquid assets, while building exposure to others—takes years to complete. We are constantly looking to evolve and improve, but the basic plan has not and will not change. Therefore, observers should not expect future letters to recount dramatic changes.…

as HMC pursues “long-term success” to “ensure that Harvard University has the means to continue its vital role as a leader in teaching and research for future generations.”

The annual financial report provides data for the endowment’s underlying dynamics, resulting in the fiscal 2018 total value of $39.2 billion. It is now possible to update the estimates made when the fiscal 2018 investment return was unveiled. That report suggested that:

- Investment returns were about $3.5 billion; the actual figure was $3.3 billion.

- Operating distributions were somewhat more than $1.8 billion—a close fit with the $1.82 billion actually disbursed.

- Gifts for endowment held steady at $500 million—underestimating the University’s friends: the actual figure was $647 million.

No estimate was made for other “decapitalization” distributions; the total now reported was $46 million, down modestly from fiscal 2017.

The Financial Year That Was

Revenue. Operating revenue increased more than $200 million, to $5.2 billion. The report cites gains in:

•executive and continuing education, up more than $47 million (about 12 percent—faster than the 8 percent growth logged in the prior year), to $458 million, sustaining robust growth at places like Harvard Business School and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Division of Continuing Education, which has become an online powerhouse and a major focal point for FAS investment and hiring. Apparently, the momentum was spread across other schools, too. For perspective, the largest single source of student income is the $586 million realized from all the graduate and professional schools’ degree programs (before netting out financial-aid costs). Undergraduate student income, before financial aid, rose $14 million (4.5 percent), to $327 million. Total scholarships rose $25.5 million (6.2 percent), to $439 million—somewhat less than half of which is attributable to students in the College;

•non-federal sponsored research grants, up an aggregate $21.5 million (8 percent), to nearly $289 million. It is somewhat troubling that federal research support was essentially flat, at $453 million for direct costs (and up about $7 million for indirect costs—essentially, reimbursement for facilities, overhead, etc.);

•the endowment distribution, up an aggregate $34 million (but just 1.9 percent), to a bit more than $1.8 billion. As reported last year, in light of earlier weak endowment investment returns—and at a time of economic and political uncertainty, and Harvard’s presidential transition—the Corporation held the distribution flat (per unit of endowment owned by each school) for fiscal 2018, and suggested that distributions could increase within a range of 2.5 percent to 4.5 percent annually for fiscal years 2019 through 2021, beginning with 2.5 percent in the current year, fiscal 2019. The increases realized in fiscal 2018 reflect gifts: new endowment units as a result of largess from The Harvard Campaign. (Deans may very well welcome the thought that another year of gifts, from the campaign’s conclusion, plus that 2.5 percent increase authorized now, might boost the distributions they receive this year to a rate of increase of 4 percent or so; given the size of the distribution, and certain schools’ reliance on it—51 percent of operating revenue for FAS, for example—the absolute numbers loom very large in their budgets and spending capacity.); and

•current-use giving, up $17 million (3.7 percent), to $467 million—another testament to the socko finish of the capital campaign.

Other revenue, a catch-all category, also chipped in, increasing $50 million (7.9 percent), to $689 million. A notable contributor was royalties from commercial use of intellectual property (up about $18 million, or 50 percent, but those results can be very volatile from year to year).

Looking ahead, it is important to note that the campaign has concluded. Pledges receivable—commitments for future gifts—declined nearly $200 million in fiscal 2017, and decreased another $110 million during fiscal 2018, a natural progression. Current-use giving might hold up, but there are no guarantees. From here, a reasonable strategy would be to anticipate the future gains from the fulfillment of the remaining $936 million of endowment pledges, and subsequent investment returns on and distributions from those assets (the campaign gifts that keep on giving forever)—and to bank on the Corporation’s willingness to increase future distributions per unit of endowment. That should offset dips in current-use giving, if any, and then some, perhaps.

Expenses. The University’s spending increased $134 million, to $5.0 billion. Compensation—salaries, wages, and benefits—accounts for half of expenditures, and rose only 2 percent: less than half the rate of growth in fiscal 2017. Salaries and wage expense increased 3 percent, also decelerating from the prior year; and employee-benefit costs were unchanged. On the surface, those results seem to confirm that deans and central administrators indeed exercised admirable fiscal discipline in a year when the core endowment distribution was held flat.

And indeed, that story generally holds true, but there is a bit of accounting noise in the number, too. Expenses for certain employee benefits, including retirees’ defined-benefit pensions and healthcare costs, are now adjusted annually for changes in the prevailing discount rate. In fiscal 2017, those adjustments increased costs significantly, accounting for a good chunk of the 7 percent increase ($39 million) in employee-benefits expense reported that year. In fiscal 2018, the interest-rate adjustment (and favorable claims experience) decreased costs, a significant swing in year-over-year reported results. In both years, health-benefits costs for active employees—the major benefits expense—rose a reported 4 percent, reflecting both an increased number of covered people and higher claims costs.

All other expenses increased by an aggregate 3 percent. Within that roughly $2.5 billion, a few items merit attention. Space and occupancy costs rose an apparent 10.5 percent, to $410 million. Some of that reflects the University’s torrid construction program (see below) and larger facilities, such as the expanded Kennedy School campus: a bigger place costs more to run. Fiscal 2019 expenses will reflect more of the same, as newly opened spaces such as the Smith Campus Center and Klarman Hall find their way into the financial statements. But the fiscal 2018 figures apparently reflect one-time costs for environmental abatement, and so the underlying trend may not imply further increases of this magnitude.

“Other expenses,” a miscellaneous, half-billion-dollar category, in fact helped fiscal 2018 look better than fiscal 2017: in the prior year, expenses were elevated by an accounting charge associated with adjusting the carrying value of Lowell House as it began to undergo renovation. There is no such charge in the year just reported. This is naturally a volatile category; work will begin on the renewal of Adams House next summer, but the magnitude of accounting charges for that facility, if any, is not known.

Finally, a continuing expense-saving of note occurs on the “interest” line. Following the refinancing of Harvard’s debt in October 2016, interest expense declined $33 million in fiscal 2017. Now, that benefit is in place for a full financial year, resulting in a further $15-million reduction in annual interest expense (to $188 million) in fiscal 2018. Those savings persist in future years.

For perspective, following the financial crisis in 2008, when Harvard was forced to borrow $2.5 billion at high interest rates to stabilize its balance sheet and secure access to liquid funds, driving annual interest costs to $299 million, that cost has decreased by more than 37 percent: a combination of astute financial management, debt reduction, and the long period of low interest rates that made cost-effective refinancing a possibility. By itself, the reduction in interest expense has contributed significantly to the University’s five-year run of surpluses.

Balance sheet and capital items. As noted, expenses for operating and occupying buildings has risen, along with the largest capital-spending program in Harvard history. The $908 million in capital spending during fiscal 2018 set a new record, just above the $906 million invested during the prior year. The highlight projects are Smith Campus Center and Klarman Hall, now complete; the Allston science and engineering center and power plant, which come on line in the fall of 2020; Lowell House renewal and successor projects; and the renovation of the Soldiers Field housing adjacent to the Business School. Greater Boston building trades and contractors should send Harvard thank-you cards monthly. Indeed, “construction in progress,” reported in the footnote on fixed assets, rose to $1.34 billion in fiscal 2018—up a quarter-billion dollars from the prior year.

Looking ahead, the completion of some of those major projects, and successor House renewals, almost certainly mean that the University will return to the debt markets to borrow more funds. Interest rates have, of late, begun to rise. Hence the importance of managing down debt outstanding (currently $5.3 billion, down from $5.4 billion in fiscal 2017) and refinancing higher-cost obligations when possible during the past several years. Harvard will inevitably again a borrower be in the near future.

One other building-related balance-sheet item of note: As reported, Harvard Medical School strengthened its finances somewhat by selling a leasehold in the majority of its research building at 4 Blackfan Circle, realizing an astonishing $272.5 million. It has the cash in hand, but for financial-statement purposes, the proceeds are recognized over time, during the duration of the leasehold interest. Hence the large increase in the “deferred revenue and other liabilities” line on the consolidated balance sheet.

A Good Problem to Have

From a financial perspective, of course, a $196-million operating surplus is a good problem to have: a relatively modest cushion, representing 3.9 percent of fiscal 2018 expenditures, and a prudent rainy-day hedge, come what may, amid robust external economic conditions; after the stunning success of The Harvard Campaign; and with the existential threats from the financial crisis of a decade ago still echoing loudly among those with fiduciary responsibility for the University’s long-term health.

Indeed, the past five years of surpluses, now aggregating nearly a half-billion dollars, are only about 2 percent of expenditures during that period. Achieving that operating margin, Hollister and Finnegan note in their letter, is deserving of at least some kudos. With suitable modesty, they point to President Faust’s “farsighted financial stewardship—especially during times of financial constraint.” During her tenure, they amplify,

…the Corporation Committee on Finance was established, consistent budgeting practices were installed across the campus, decisionmaking has been guided by new multiyear financial and capital planning processes, and clear policies have been created with respect to University liquidity, operating reserves, philanthropy for capital, and facilities renewal spending. Through both her championing of sound financial practices and her leadership role in the success of the capital campaign, President Faust’s legacy of financial stewardship will benefit the University for generations to come.

All true.

But in the near term, not everyone will be so generous about awarding credit. As the endowment tax shows, and opinion surveys confirm, not all members of society look kindly on elite research universities. The current litigation alleging that Harvard discriminates in undergraduate admissions has detailed for the public long-established practices that have benefited legacies and financial supporters (as is the case at peer institutions): not new news, but challenging optics at a time of populist upheaval in the electorate. Internally, Harvard’s staff members (many of them now working with an expired contract), the recently formed graduate-student union, and no doubt even nonunionized faculty members (whose compensation has grown more slowly than that of unionized workers) can make the case for their economic needs and wants. [Updated October 25, 2018, 1:50 p.m.: The University and the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers, the largest union, announced this afternoon that they had reached a new three-year contract agreement, replacing the contract that expired September 30; details will be disclosed to members and managers in the next few weeks, with a ratification vote scheduled for December 4.]

The surpluses Harvard has accumulated arise from the schools’ operations, but unevenly. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences just inched into the black in fiscal 2018—and then only because it is harvesting the proceeds of restructuring its long-term debt with the University, and had a banner year for current-use giving as the campaign ended. The Medical School, as noted, is also taking extraordinary steps to stem a decade-long tide of red ink. Presumably, the professional schools that do not operate expensive laboratories have been performing strongly in the current, favorable economic environment and on the heels of their capital campaigns.

The opportunity and challenge, then, are to apply the hard-won, happily realized surpluses to Harvard’s core research and teaching missions; to make those investments, and their value to society at large, more visible (perhaps President Bacow’s highest priority); to maintain discipline when the current, exceptionally long economic expansion falters; and, to sustain the University’s strength by realizing the hoped-for improvements in the performance of the endowment.

The University and its leadership approach those opportunities and challenges from a position of fortunate financial strength. Given the rest of the agenda, and Harvard’s dire circumstances a decade ago, it is good to have that worry resolved for now.

Read the full texts of Harvard’s annual financial reports here. Read a Harvard Gazette story about the fiscal 2018 results—a conversation with executive vice president Katie Lapp and CFO Thomas Hollister—here.