This November 17 marks the 135th iteration of The Game—and more vividly, the fiftieth anniversary of the titanic “Harvard Beats Yale 29-29” edition: a football contest made indelible, even beyond hardcore fans, not only by the sequence of plays that led to the outcome, but by the temper of its times. (It is the subject of an eponymous documentary film by Kevin Rafferty ’70.) Now, George Howe Colt ’76, author of The Big House and other acclaimed books, digs deep—from his own boyhood memories of attending that game, to searching interviews with the players—to convey the context, and the breathtaking action, that created the continuing resonances he captures completely in The Game: Harvard, Yale, and America in 1968.

In the following excerpt from chapter four, “The Melting Pot,” Colt examines the team’s demographics: a window into the 1960s transformation of Harvard and other elite schools from bastions of privilege to something somewhat more diversified, and more closely attuned to the country at large—controversial changes that were perhaps more advanced among athletes than among undergraduates at large.

—The Editors

When Ray Hornblower showed up for the first day of Harvard freshman football practice in late summer 1966, some of his teammates wondered whether he’d wandered into the wrong place by mistake. The slender halfback with blue eyes, blond hair, dimpled cheeks, and upper-crust accent—and a funny last name masking-taped to the front of his helmet—looked more like a choirboy than like a football player. (He had, in fact, been singing in choirs since he was seven.) “Who’s this Hornblower guy?” Gus Crim, the 210-pound fullback who had turned down Ohio State to come to Harvard, muttered to Rick Berne, a six-two, 230-pound defensive tackle. “I’m playing on a team with this?” And then they saw the choirboy run. He started out eighth on the depth chart; by the time the season opened, he was first.

* * *

Ralph Hornblower III was not, as was often assumed by Harvard fans, a Proper Bostonian. He grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut, and summered at Squibnocket Farm, a 1,500-acre family compound on Martha’s Vineyard. His father worked on Wall Street as a partner in Hornblower & Weeks, the brokerage founded by Ray’s great-grandfather in 1888. But on both sides of the family, college had, for generations, meant Harvard. His parents had taken him to every Harvard-Yale game since he was six, and he had thrilled to the exploits of Charlie Ravenel ’61, the undersized quarterback from Charleston, South Carolina, whose improvisational daring had earned him the nickname “the Riverboat Gambler.” Despite his slight frame, it was assumed that young Hornblower would one day play football for Harvard. His father’s father had captained the hockey team in 1911; his mother’s father had been the intercollegiate 440 champion in 1909. But the best athlete in the family may have been his mother. Legend had it that her Beaver Country Day softball team had gotten together at a reunion and beaten a group of Harvard freshmen. Ray would always remember the autumn afternoon when he and his mother were tossing a football on the back lawn. Ray was nine. His mother, wearing a fur coat, had waved the ball and called out, “Okay, Ray, run at me!” And Ray had run at her, as fast as he could, driving his head into her stomach and knocking her back a yard or two. “My God, you really hit!” she exclaimed, beaming. From that moment on, Ray was determined to run the football with total abandon.

Two years later, while 11-year-old Ray was starring on his sixth-grade football team, his mother lay in bed, dying of leukemia. One afternoon, he overheard her on the phone, telling a friend how her son was tearing up the Fairfield County private school league. “I know he’s going to make it,” he heard her say. “He’s going to be the next Charlie Ravenel.” A few months later, she was dead.

As a middle-aged man, Hornblower would look back and see that much of what drove him on the football field was a desire to vindicate his mother’s faith in him. To that end, he might have been wise to prep somewhere other than St. Paul’s, a small boarding school in the woods of southern New Hampshire known more for its prowess at squash than for its mastery of football. A St. Paul’s football team wouldn’t begin playing other schools until 1962, a year before Hornblower arrived. Hornblower became a star at St. Paul’s, running with quicksilver elusiveness and throwing the option pass with an accuracy his father attributed to years of family duck-hunting on the Vineyard. But his star didn’t shine far beyond Concord. When his high-school coach phoned John Yovicsin to tell him about his talented senior, the Harvard coach seemed to be under the impression that St. Paul’s was a big Catholic school up near Manchester.

At Harvard, Hornblower led the freshman team in scoring. The following summer, he came down with mononucleosis. He spent most of August, when he should have been running wind sprints on the beach, lying on a couch at Squibnocket Farm and gazing at the Atlantic. Hornblower began his first varsity season on the bench, but in the third game, when the reserves were sent in during a rout of Columbia, he took a pitchout and sped 40 yards for a touchdown. Two games later, he played so well in the third quarter of a tight contest against Dartmouth that although the outcome was still in doubt, the coaches left him in. “Little Ray Hornblower,” as the Harvard Alumni Bulletin referred to him in its account of the game, had been a starter ever since.

For Harvard alums, many of whom came from similarly privileged backgrounds, Hornblower’s emergence was a boon; he was one of their own. Whenever he ripped off a long run, a frisson of self-satisfaction rippled through the choice seats between the forties, like a gust of wind rippling the surface of the Charles. Hornblower wasn’t the only dyed-in-the-wool New England preppie on the 1968 team—Tony Smith ’69, the ridiculously handsome second-team end, had arrived at Harvard by way of New Canaan and Choate—but Hornblower was the only starter. Jack Fadden, the Harvard trainer, himself the son of Irish immigrants, called him the Last of the Mohicans.

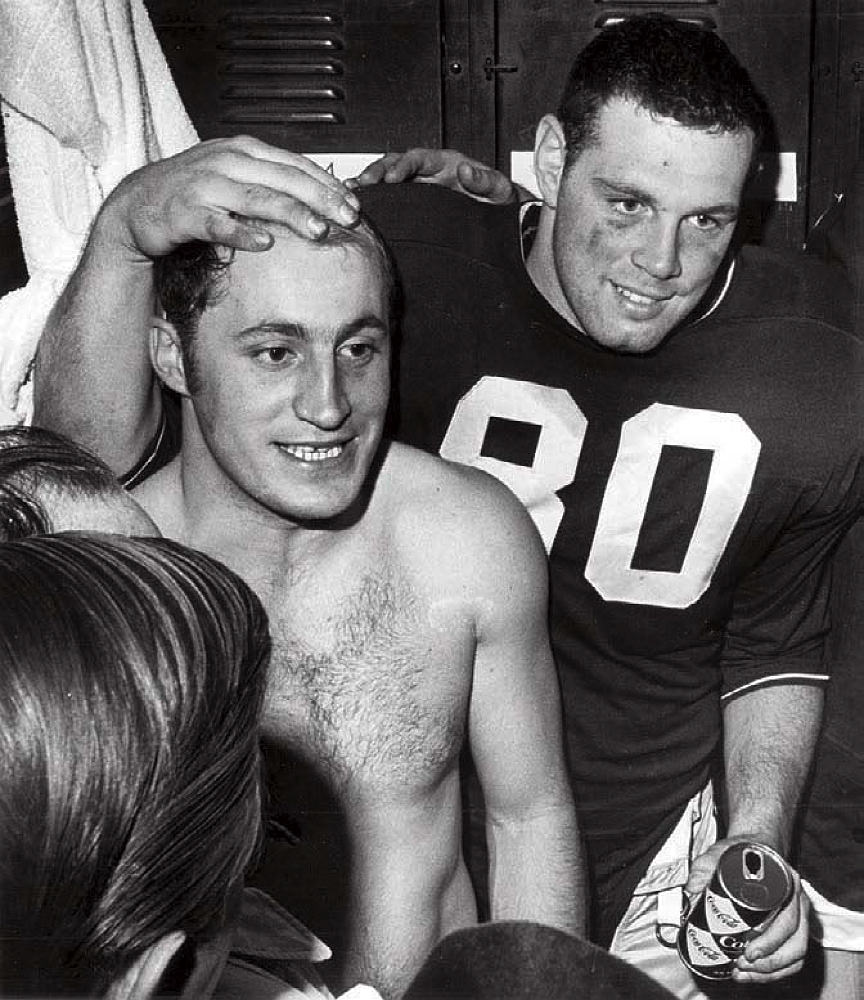

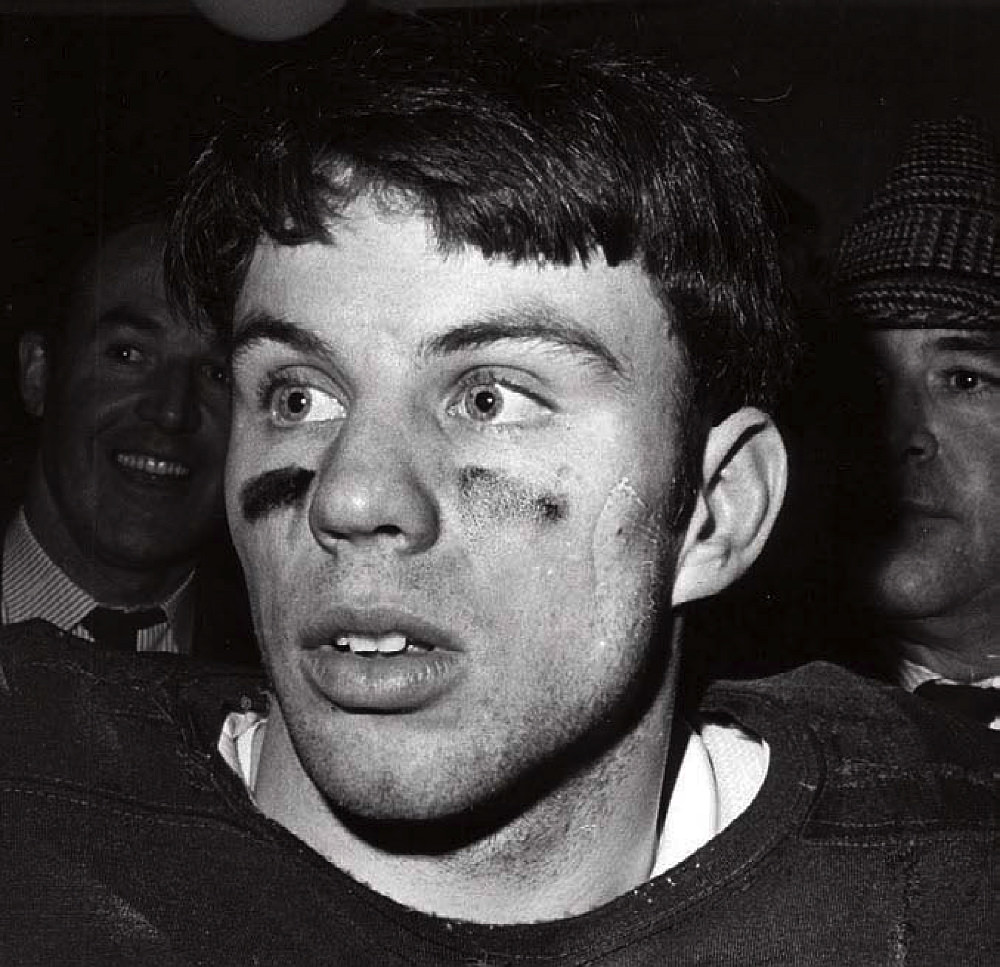

(Click on arrow at right to see a gallery of images.) Celebrating it all are quarterback Frank Champi (left) and halfback Richard "Pete" Varney (right), who caught Champ's tying two-point conversion pass.

Photograph Frank O'Brien/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Celebrating it all are quarterback Frank Champi (left) and halfback Richard "Pete" Varney (right), who caught Champ's tying two-point conversion pass.

Photograph Frank O'Brien/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Harvard coach John Yovicsin and halfback Ray Hornblower III. A tackle on the first play of the fourth quarter forced Hornblower from the Game.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

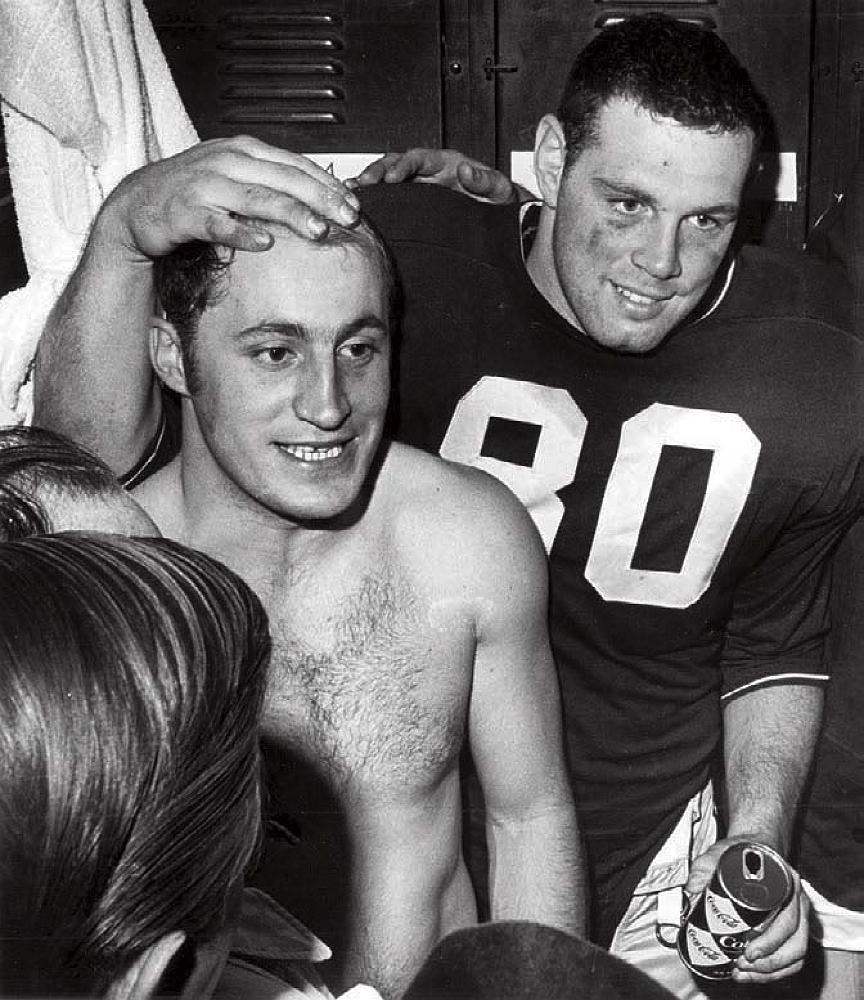

Left guard Tommy Lee Jones, an eighth-generation Texan, reflected some of the diversity of the team.

Photograph by Dick Raphael

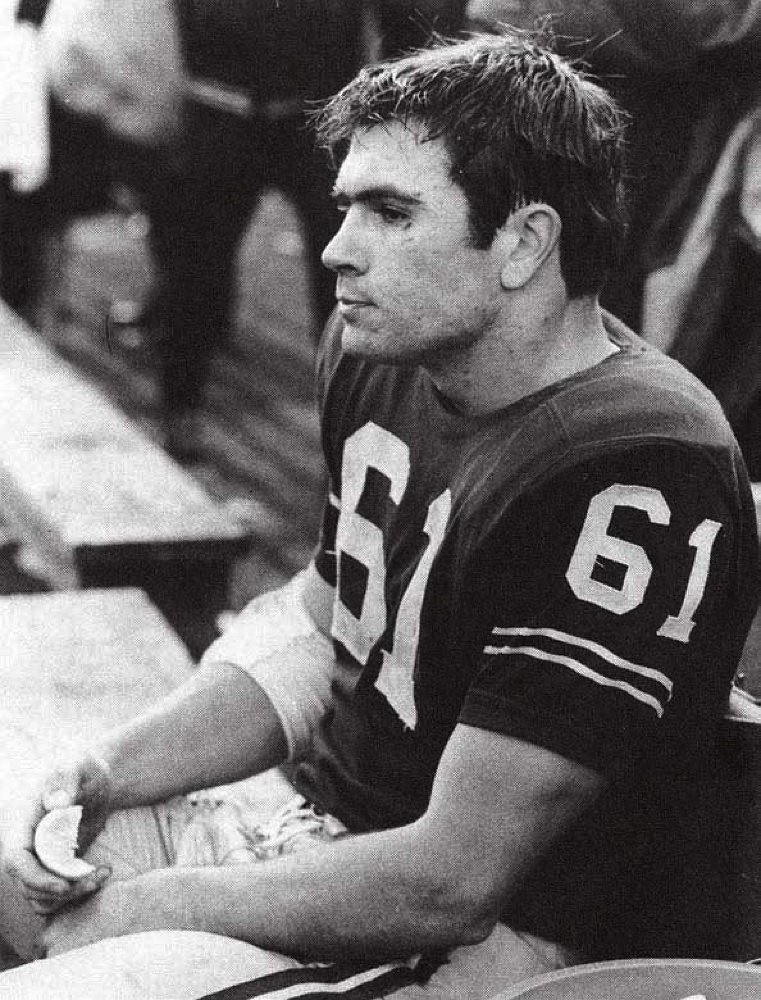

Italian-American captain Vic Gatto

Photograph Frank O'Brien/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

To his teammates, Hornblower was the kind of self-assured rich kid who seemed to have been born and raised in Harvard Yard. Although the WASP world of final clubs and debutante balls was losing its hold in the anti-establishment sixties, there remained redoubts to which private schoolers could retreat. Hornblower lived in Eliot House, the “preppie ghetto” whose master, the famously patrician classics professor John Finley, handpicked its students and was said to favor applicants from St. Paul’s, Groton, and his own alma mater, Exeter. Saturday night after the football game, while many of his teammates were guzzling keg beer at the Pi Eta, Hornblower could be found nursing a bottle of Budweiser at the Owl, a final club whose alumni included Harry Elkins Widener ’07. Yet the princely Hornblower wasn’t a “snot,” as stuck-up preppies were called. He had a disarmingly bluff manner and something of an egalitarian streak, sponsoring Crim, Berne, and several other public-school teammates for Owl Club membership. The teasing to which his fellow players subjected him was good-natured. When Fritz Reed ’70 caught sight of Hornblower in the locker room, fastening garters to his black dress socks on his way to an Owl Club formal dinner, the offensive tackle razzed the halfback unmercifully. Knowing that Hornblower’s girlfriend was the great-granddaughter of Teddy Roosevelt, the players asked, “Hey, aren’t you dating Margot Rockefeller?” Hornblower would shake his head in exasperation and respond, “Her name is Roosevelt, for God’s sake!” Hornblower’s play made him immune to any real barbs. That was one of the reasons he liked football. It was the same reason why generations of players from less privileged backgrounds had liked it: on the field your background didn’t matter. The only thing that mattered was whether you could turn the corner on a defensive end.

Hornblower’s breezy self-assurance wasn’t quite as breezy as it seemed. If some of his public-school teammates felt out of their element in classrooms dominated by jaded preppies from St. Paul’s and Groton, Hornblower felt out of his element on the football field among the gritty players from local powerhouses like Everett and Malden Catholic. He was aware that prep-school athletes, who tended to play the glamour positions like halfback and quarterback, were assumed to be soft and had a reputation for quitting when they realized they weren’t going to be first or second string. Hornblower was determined to subvert the stereotype. On warm-up laps around the field, when most players ran just fast enough not to get yelled at by the coaches, Hornblower would race out in front, straining to be first. He knew that his teammates were probably cursing him under their breath, muttering, “What an asshole,” but he had to be first, every practice, every day.

Hornblower had a secret weapon. Sophomore year, Margot Roosevelt ’71 introduced him to a psychiatrist she’d met at the Harvard Christian Fellowship. Dr. Armand Nicholi, a Harvard Medical School faculty member, was a specialist in Freud. He was also a former varsity football player at Cornell who, at a time when sports psychology consisted largely of coaches calling their players pussies in an attempt to goad them to greater heights of aggression, was interested in how psychology could be used to maximize athletic performance. He started working with Hornblower on what, years later, would be called visualization techniques. He encouraged Hornblower to set specific goals. Hornblower decided that his goal in 1968 was to run for 100 yards each game.

* * *

Even Harvard’s most devoted fans assumed that the team’s three-game unbeaten streak would come to a halt against Cornell on October 19. Cornell had 27 lettermen coming back from a team that had finished third in the league. Their defense boasted nine returning starters, including the league’s largest player, a six-foot-five, 250-pound tackle who had been an honorable-mention All-American the previous year.

Under a steady rain in front of 16,990 hardy fans, Harvard’s defense held Cornell to eight first downs and didn’t allow them inside the twenty. Although the footing was sloppy, senior quarterback George Lalich threw for 102 yards, while his classmate, halfback Vic Gatto, ran for 76, in the process breaking Harvard’s career rushing mark, set in 1953. It would be Hornblower, however, who propelled the offense in the team’s 10–0 victory, running 26 times for 138 yards, earning honors as Ivy League Back of the Week.

* * *

For much of the first half of the twentieth century, Harvard was composed largely of students like Hornblower: New England prep schoolers who had grown up assuming that admission to the college was their birthright. Abbott Lawrence Lowell, scion of one of Boston’s oldest, wealthiest, and most socially prominent families, and Harvard’s president from 1909 to 1933, had done his best to keep it that way. To the consternation of Lowell and many alumni, Harvard’s demographic complexion began to change under his successor, James Bryant Conant. A brilliant chemist who had grown up in middle-class Dorchester, Conant was troubled by Harvard’s social and economic exclusivity and encouraged a more meritocratic admissions policy that would make it a truly national institution. “We should be able to say that any man with remarkable talents may obtain his education at Harvard whether he be rich or penniless, whether he come from Boston or San Francisco,” he wrote in his first annual report. Slowly, Harvard’s student body became, relatively speaking, more socially, ethnically, and geographically diverse. In 1953, for the first time, there were more public schoolers than private in the entering freshman class—a milestone not quite so egalitarian as it seemed, given that only 2 percent of American high-school graduates attended private schools.

The demographics of the College, were, in fact, coming closer to those of its football team. An oft-told joke had it that to play for Harvard you had to have been born on Beacon Hill or belong to the Porcellian, the oldest and most prestigious of Harvard’s final clubs—unless you were one of the South Boston Irishmen recruited to block for them. In fact, the football team had long been a pocket of ethnic and socioeconomic variety. As far back as the turn of the century, when 80 percent of Harvard students were private-school graduates, a story in the Crimson complained that immigrant sons from public schools were pushing prep schoolers off the squad.

On the 1968 roster, 28 of 88 players had attended private school, but the number was misleading; of those, 12 were PGs: players who, after graduating from Boston-area public schools, were encouraged to undergo a year of postgraduate polishing, on scholarship, to prepare them for the academic and social demands of Harvard. Indeed, six players on the team had PG’d at Exeter, which over the years had come to serve as a kind of de facto farm team for Harvard football—and, at the same time, a way station at which future Harvard players could boost their test scores to an acceptable level.

More than a third of the players on the 1968 team had been culled from Boston-area public and parochial schools—“local boys,” as the sportswriters called them, many of them the sons or grandsons of immigrants who had arrived in the great tide that had transformed the city at the turn of the century. A critical mass of seniors, including the captain, Gatto, were Italian-American, and calls of cinque or otto could occasionally be heard in the locker room as they played morra, an ancient Italian game, not unlike rock-paper-scissors, in which contestants threw out a hand, showing zero to five fingers, and guessed what the sum of all the fingers would be. More than a few players were Irish-American, including cornerback Neil Hurley ’70, whose parents had emigrated from Galway and County Cork as teenagers and bequeathed their son the faint brogue that overlay his Boston accent. Among the seniors, Ted Skowronski’s grandparents were from Poland, George Lalich’s from Serbia, and John Ignacio’s father, a geographic outlier, had been a farmer on Guam. (Harvard’s 1968 press book contained a “Pronunciation Guide”—unnecessary in the days of Hamilton Fish and Endicott “Chub” Peabody—that provided broadcasters with phonetic spellings: “ska-RON-ski,” “ig-NAH-she-o,” and so on.) While the locker room chatter was still dominated by Boston-ese, Yovicsin’s alumni recruiters were bringing in an increasing number of “horses”—as football players were referred to in admissions parlance—from farther afield: safety Tom Wynne ’69 was from Arkansas; defensive tackle Ed Sadler ’70 was from Tennessee; defensive end John Cramer ’70 was a fifth-generation Oregonian whose great-great-great-grandmother had crossed the Great Plains by covered wagon in 1864. The team’s annual end-of-preseason New England clambake was the first time Cramer had seen a lobster. He had to ask his Boston teammates for operating instructions.

The team varied by age (24-year-old Vietnam veteran Pat Conway ’67 [’70] was the oldest, 18-year-old safety Fred Martucci ’71 the youngest); marital status (Lalich, Joe McKinney ’69, and defensive back Ken Thomas ’70 were married and lived off campus); temperament (there were free spirits like Alex MacLean ’69, teetotaling Midwesterners like Crim, and hard-partiers like defensive tackle Steve Zebal ’69); and interests (MacLean and Berne had their SDS meetings, punter Gary Singleterry ’70 his Christian Science services). You never knew what hidden talents a teammate might possess. That fall, Joe McGrath ’69 was struggling with a midterm music paper in which he had to analyze a Bach fugue. He asked his fellow lineman Fritz Reed, who was also taking the class, for help. Reed took McGrath and the score down to the Adams House music room, where he sat at the piano and sight-read the piece flawlessly before explaining to the astonished McGrath how the fugue was structured.

The most unusual résumé on the team may have belonged to Tommy Lee Jones ’69. The son of a cowboy turned oil rigger, Jones was an eighth-generation Texan whose life had revolved around hunting, fishing, and football until the afternoon during his junior year in high school when he wandered into a room where a group of students was rehearsing for a production of Mr. Roberts. Jones was spellbound. He auditioned for the school’s next show, Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood, and was cast in a small part. Since arriving at Harvard, the “talented thespian,” as the press book called him, had performed in plays by Pinter, Euripides, and Brecht; the previous spring he had won raves in the title role of a multimedia adaptation of Coriolanus, for which he had dragooned several linebacker teammates into appearing onstage as appropriately muscular centurions. Being both a jock and a “Loebie” (Harvard actors spent much of their time at the college’s Loeb Drama Center) took some juggling. After practice, while his teammates dawdled in the locker room, Jones sometimes had to rush off to rehearsal, occasionally in costume. “Are you bolting so you can go do that to‑be-or-not-to-be shit?” Reed would shout.

Offstage, Jones was a man of few words, which he measured out in a gravelly Texas twang and punctuated with long, enigmatic pauses. The first week of freshman year, Joe McGrath was unpacking in his room in Mower Hall when he heard a strange, rhythmic thumping. He went outside and found a sturdy-looking freshman in cowboy boots, squatting on his haunches, throwing a hunting knife into the trunk of a tree. McGrath introduced himself. “I’m Tommy Lee Jones,” the young man replied, and went right back to his throwing. Jones, who kept his radio tuned to the only country station in Boston, could occasionally be heard croaking scraps of Hank Williams in a tuneless bass in the locker room.

Jones belonged not to Pi Eta, the jock-dominated social club, but to the Signet Society, the invitation-only literary club that counted T.S. Eliot and James Agee among its former members. An English concentrator, he was writing his honors thesis on the influence of Catholicism on the work of Flannery O’Connor. One evening, John Ignacio found himself sitting next to Jones at dinner at the Varsity Club, discussing Look Back in Anger, the play by John Osborne. Ignacio soon realized that while he was talking in a basic way about its plot, Jones was dissecting its structure, its characterizations, its place in contemporary drama. As he listened, Ignacio realized that this was what people meant when they said that you’ll learn more at Harvard from the people you have dinner with than from your professors.

At six feet, 195 pounds, Jones was an unusually sturdy leading man (“hulking,” said the Crimson, in its review of The Caretaker), but the smallest player on the offensive line. Although he wasn’t one to overpower an opponent, like Skowronski, he was the fastest of the linemen, had excellent technique, and played with an almost unsettling intensity. Guard Bob Jannino considered him the most focused person he’d ever met. The team could be ahead by four touchdowns in the final minute and Jones would still be going at it as if the game were tied. In practice, when the coaches instructed the players to perform a drill at half speed, most were grateful for the respite, but Jones continued at full throttle.

* * *

At many big-time football schools, players lived in the same dorm, hung out together, and became a distinct cult, set apart from their classmates. At Harvard, athletes were scattered throughout the campus—though Winthrop House had such a profusion that visiting Cliffies joked about making sure to bring along a piece of raw meat. Even so, the team spent more time together than many families. Practice ran from five to seven—it started late so premeds could finish their labs—but most players came early to get their ankles taped, and after the long walk to the Varsity Club for dinner, there were meetings, films, and scouting reports. Some nights, they were lucky if they got back to their rooms by ten to begin studying.

Although most of the players went their separate ways off the field, many of them belonged to the Pi Eta, which was quartered in a three-story brick building on Boylston Street. On Saturday nights after the game, they gathered with their guests at “The Pi” to drink beer and dance. On Sunday afternoon, players convened in the basement to watch the NFL doubleheader on the club’s color TV, while linebacker Gerry Marino and cornerback Mike Ananis prepared the ritual Pi Eta Sunday-night spaghetti supper in the kitchen. The two seniors had assembled the ingredients on Saturday morning before the game, getting up early to take the subway to Haymarket, where Marino, all four of whose grandparents had emigrated from Sicily, went from stall to stall, haggling in pidgin Italian as he selected tomatoes and peppers and onions and garlic, before heading to Capone’s butcher shop for pork chops, short ribs, and ropes of hot sausage. On Sunday, Marino prepared the bolognese sauce; Ananis, the grandson of Lithuanian immigrants, was relegated to making the salad.

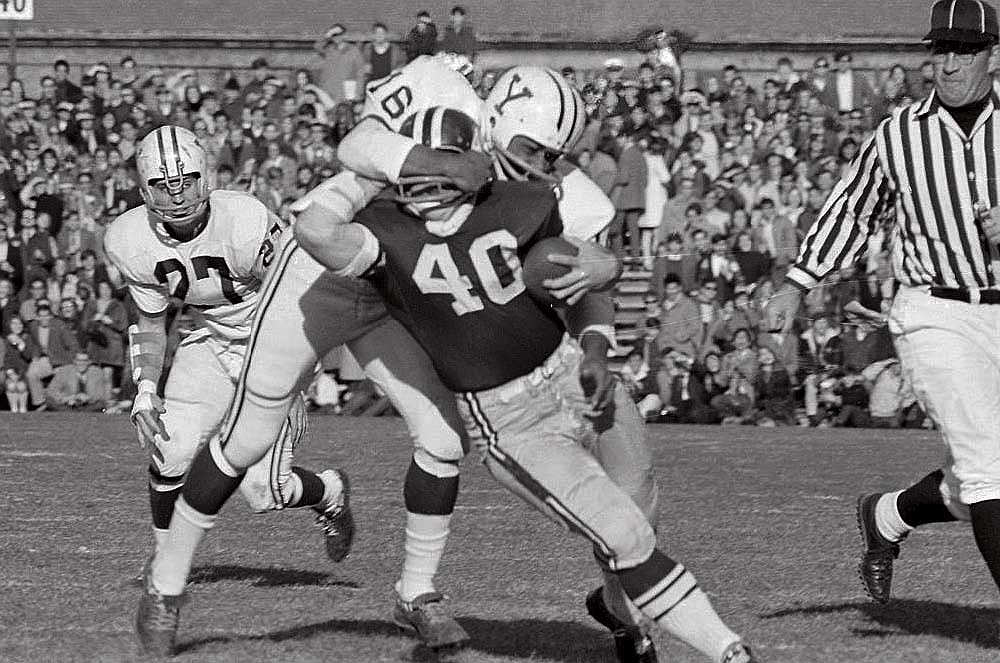

(Click on arrow at right to see a gallery of images.) Vic Gatto ran into trouble during the first quarter when he was tackled by Yale's Kurt Schmoke (later a Harvard Law School J.D. and the future mayor of Baltimore).

Photograph by Bettmann/ Getty Images

Vic Gatto ran into trouble during the first quarter when he was tackled by Yale's Kurt Schmoke (later a Harvard Law School J.D. and the future mayor of Baltimore).

Photograph by Bettmann/ Getty Images

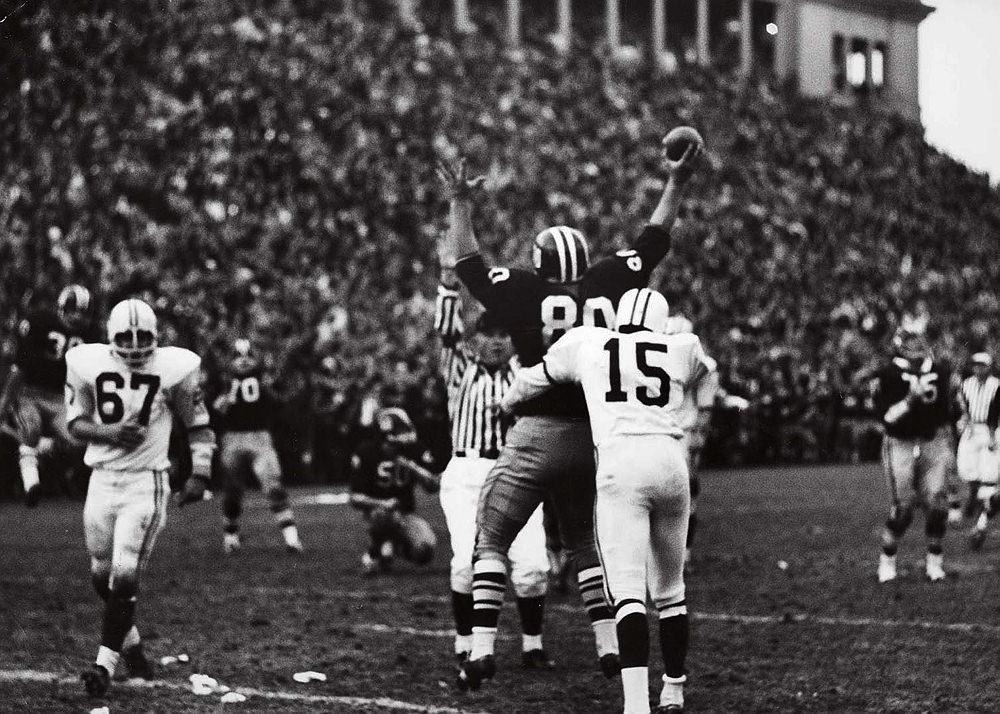

In the fourth quarter, with 19 seconds left, Yale led by eight points.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

Pete Varney brandishes the "winning" catch as Gus Crim (30), Bob Dowd (70), Ted Skowronski (50), and Fritz Reed (75) react.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

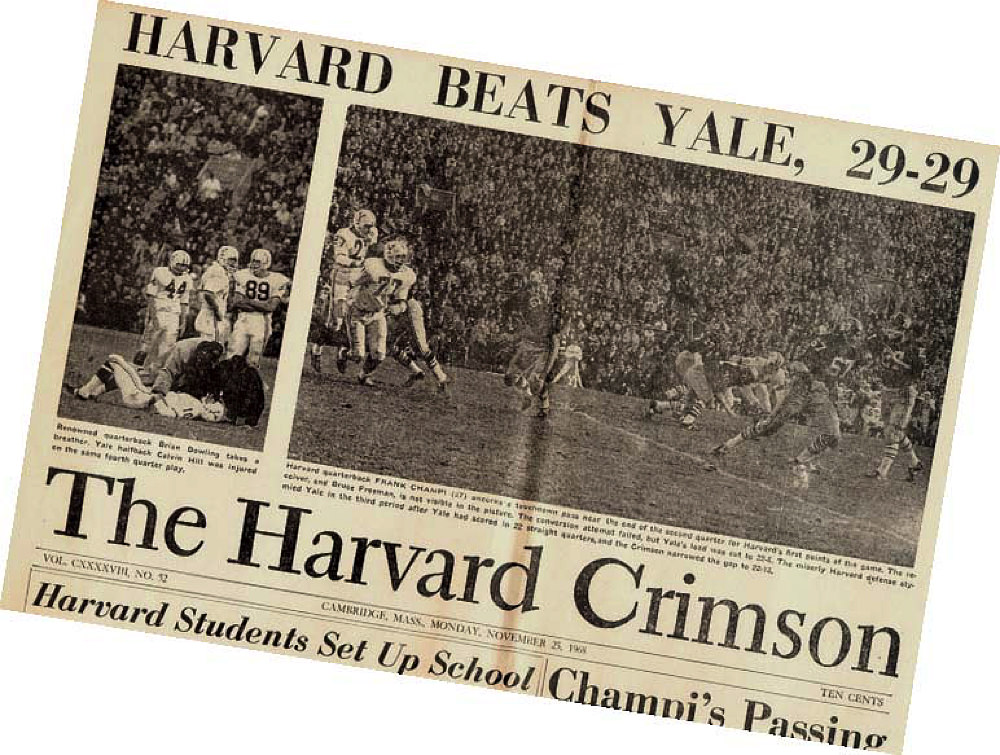

The Monday morning front page of The Harvard Crimson, immortalizing the quote of an anonymous undergraduate

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

Ananis, another local boy—his father, a former All-American running back at Boston College, owned a Cambridge bar—was the kind of selfless player it took to make a team. The five-foot-nine senior had started at cornerback the previous year. In the Yale game, he had intercepted two Brian Dowling passes and was on the verge of intercepting a third when he slipped in the mud and gave up the winning touchdown bomb. This year, when he separated his shoulder in the final preseason scrimmage, he was devastated. But Ananis, for whom sports had been a refuge after his mother died of cancer when he was nine, decided that if he couldn’t play, he’d do everything he could to prepare his replacement, sophomore Rick Frisbie: instructing him in practice, encouraging him from the sideline during games, going over his assignments with him during time-outs. He continued to custom-make T‑shirts for new members of the Headhunters, as Harvard’s kickoff team was known, staying up late at his Lowell House desk and painstakingly Magic Markering a skull skewered by a bloody knife over the word HEADHUNTERS in Hells Angels–style lettering, with the player’s name inscribed on the skull’s forehead.

* * *

In 1903, William James, speaking at the Commencement Dinner on “The True Harvard,” suggested that people were drawn to the College, among other reasons, “because she cherishes so many vital ideals, yet makes a scale of value among them; so that even her apparently incurable second-rateness (or only occasional first-rateness) in intercollegiate athletics comes from her seeing so well that sport is but sport, that victory over Yale is not the whole of the law and the prophets.” James wrote those words at a time when the football team’s fans were so numerous that Harvard had just begun building what was then the country’s largest stadium to accommodate them. Nonetheless, Harvard, where it was considered a virtue never to be caught caring too much about anything (especially Harvard), had long prided itself on its ability to keep athletics in perspective. When Yale scored its first touchdown in the 1934 Harvard-Yale game, Harvard students held up a placard that read “Who Gives a Damn?” By mid-century, Harvard students had given up writing fight songs in favor of writing satires of fight songs, like that composed in 1945 by sophomore Tom Lehrer (and rendered in hoity-toity Brahmin-ese):

Fight fiercely Harvard, fight, fight, fight,

Demonstrate to them our skill.

Albeit they possess the might, nonetheless we have the will!

How shall we celebrate our victory?

We shall invite the whole team up for tea.

In the forties and fifties, prior to John Yovicsin’s arrival as coach, Harvard students may have had little choice but to feign being above it all because the team was so inept. In the sixties, the alumni still lived and died with the team, albeit quietly—“at Harvard it isn’t considered proper to show any emotion at a football game,” a player lamented—but the students who attended games viewed the proceedings with ironic condescension, as if they were observing a quaint, mildly amusing ritual from an earlier era. “I don’t mind if we lose, so long as we lose interestingly,” said one.

For the players, Harvard’s apathy took some getting used to. Most of them came from public high schools where football players were treated not merely with respect but with adoration. At Harvard, few people other than their roommates knew they played, and, if they did know, they weren’t likely to pay much attention. Harvard was full of people who were good at what they did, and the fact that what you were good at was playing football was considered no more worthy of veneration than singing for the Glee Club or writing for the Advocate, the college literary magazine. The players, while larger, on average, than their fellow students, didn’t dress much differently, and in most cases their hair was appropriately shaggy. They could walk the campus in virtual anonymity. On the Friday afternoon before the Dartmouth game, Vic Gatto was sitting in the hallway of Dillon Field House being interviewed by a writer for the Globe. Several passing students asked him for directions to the weight room. Not one of them recognized the captain of the undefeated Harvard football team.

If anything, being a football player at Harvard carried something of a stigma. Most of the players wouldn’t have been caught dead wearing their “DeeHa” (DHA: Department of Harvard Athletics) sweatshirts to class, lest they risk being dismissed as a jock (the adjective dumb was implied) who might not have been admitted had he been unable to catch a buttonhook or manhandle a quarterback. “I hate snobbery toward jocks,” observed Harvard sociologist David Riesman, who hardly did athletes a favor when he added, “The jocks at Harvard are no threat to anybody. They don’t even get the prettiest girls.”

* * *

In 1968, Harvard students were especially disinclined to get excited about football. Ever since the first football game had been played in 1869, the sport, with its elaborate strategy, precise formations, and unbridled violence, had been likened to war. For almost a century, football’s association with war had been embraced. During the sixties, however, that association was viewed with disdain, at least in Cambridge. The qualities football prized—discipline, conformity, aggression, and teamwork—were the antithesis of peace, love, and doing your own thing. Many students considered it frivolous or even immoral to cheer young men running up and down the field in mock battle when, on the other side of the world, young men were fighting and dying in earnest. Far better—and far cooler—to chant “HELL NO, WE WON’T GO!” in Harvard Yard than “HOLD THAT LINE!” at Harvard Stadium. More than a few students who attended the games were there less for the football than for the halftime show, in which the Harvard Band—irreverent, hip in a nerdy way, and decidedly antiwar—could be counted on to comment acidly on the issues of the day. The band’s antics infuriated many alumni, who believed that the stadium on a Saturday afternoon was one of the few places left where the world still seemed right side up, where Harvard still resembled the Harvard they had known.