Of the more than 3,000 books that Harry Elkins Widener, A.B. 1907, collected during his short lifetime, one is missing from his Memorial Library: a rare 1598 edition of Francis Bacon’s Essays. Too special to ship home separately with the other items he had acquired during a London book-buying trip, the small volume was with him when he boarded the Titanic on April 10, 1912. After he perished in the shipwreck, a legend emerged about his attachment to the book. In one version, he refused to board a lifeboat because he had to retrieve it from his cabin; in another, he told his mother he had placed the volume in his pocket, declaring, “Little Bacon goes with me!”

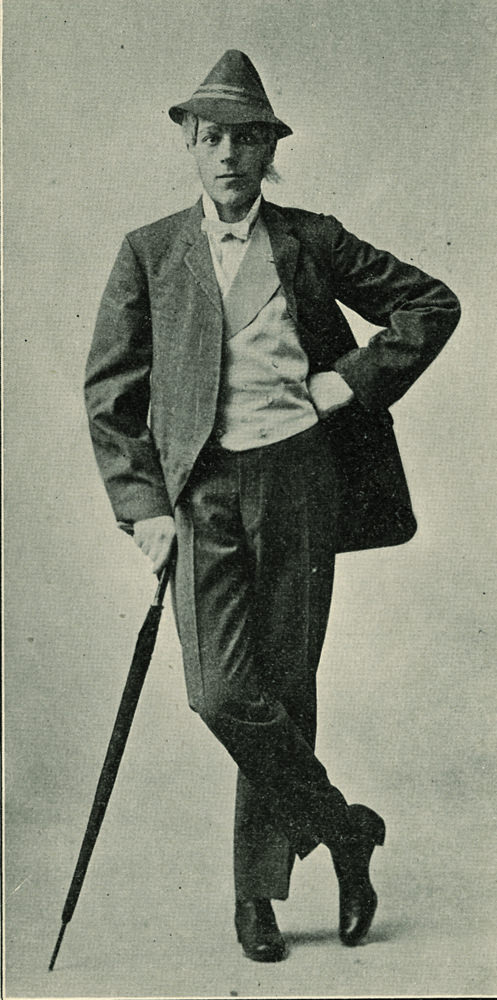

Harry Widener around 1907

Portait courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

From the outset, the Bacon anecdote was linked to Widener’s tragic, untimely death. But the volume also speaks to his character in life, and many of its short treatises seem carefully calibrated to Widener’s own pursuits. The first essay, “Of studie,” would have resonated with his constant devotion to learning. According to Bacon, that process cannot take place in isolation: studies “perfect nature, and are perfected by experience.”

Widener abided by this philosophy throughout his life. In high school, he took part in almost every aspect of student life, including the tennis team, the Cadet Corps, and the debating club. Eventually, he hoped to build his own educational institution, uniting his great passions for books and scholarship. Meanwhile, though, he made plans to benefit one already in existence. “I want to be remembered in connection with a great library,” he famously told a friend before departing for England in the spring of 1912—by which point he had already made arrangements for his collection one day to benefit the students and scholars of his most beloved institution, Harvard.

Though born to extreme wealth (amassed from railroads, steel, and tobacco, among other ventures), he often told his regular booksellers that he had taken on as much “debt” as he could carry. A convenient line, to be sure—Widener was as savvy as he was charming and amiable—but also a testament to his caution and inclination to follow another of Bacon’s assertions: “Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.” Widener preferred to chew and digest a few books, rather than taste the lot. Books to him were personal friends. He “lived with his beloved volumes,” a friend wrote, “for his library was his bedroom, his study, his workshop.”

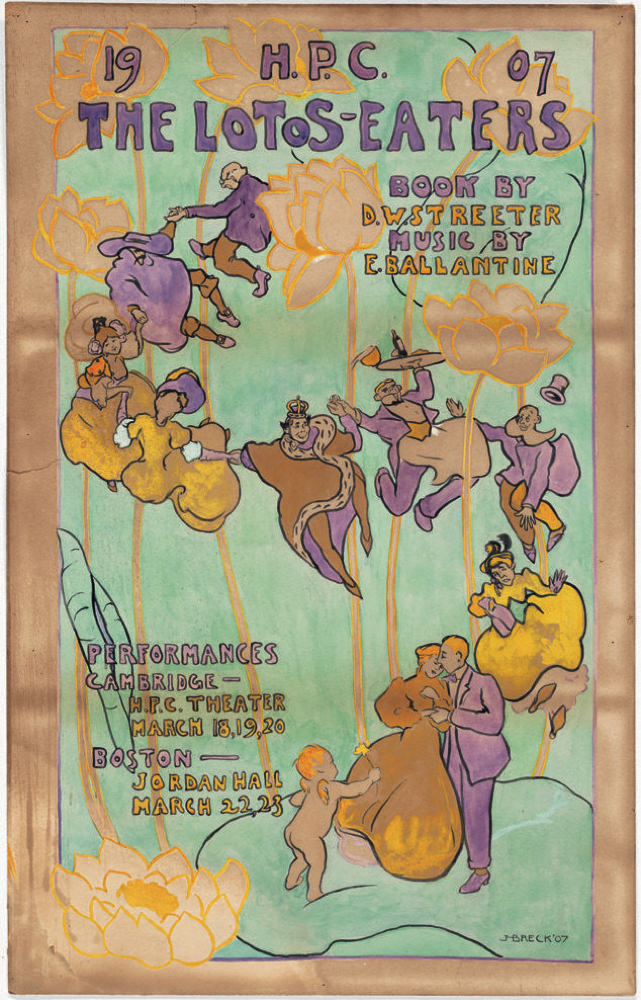

Widener played Abadiah Burdock Butterworth, husband of a “masterful woman,” in the 1907 Hasty Pudding show, The Lotos-Eaters

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Yet he had difficulty resisting certain items. In February 1911 he was offered an extremely rare volume, The Undergraduate Papers, a short-lived nineteenth-century magazine, published by Oxford undergraduates, containing four essays by the future poet and playwright Algernon Charles Swinburne. This would have been a treasure for any bibliophile, but to Widener, it was also a window into the experience of a few students who would go on to make their marks on the literary world. He initially refused it, but in May he caved, with an urgent four-word telegram: “will take undergraduate papers.”

It is not hard to see the volume’s appeal. Its epigraph, “And gladly wolde we learn and gladly teach,” slightly misquotes a passage from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, describing an Oxford scholar who preferred 20 books at the head of his bed to rich robes or fancy musical instruments. Years later, Widener’s classmates rephrased a similar quotation from Ecclesiasticus to commemorate him in his Memorial Library: “He labored not for himself only, but for all those who seek learning.”

The Lotos-Eaters

Poster courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

The volume also reflects Widener’s passion for theater. Swinburne’s first essay, “The Early English Dramatists,” discusses Shakespeare’s contemporaries Christopher Marlowe and John Webster. As a high-school senior, Widener had acted in a student production, A Scrap of Paper, playing a scientist whose most memorable moment came as he unknowingly used a crucial love letter to wrap a “rare beetle specimen.” That performance earned praise from the student newspaper: “special mention should be made of...Widener as the placid naturalist, very much taken up in his work.” Given his future endeavors, he was exceedingly well cast.

At Harvard, he joined the Hasty Pudding Club, performing in its 1907 production, The Lotos-Eaters. Observers often note that his Pudding involvement inspired his purchase of illustrated costume-books, but his interest in theater ran even deeper, and he acquired valuable seventeenth-century collections of the playwrights Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher, and Ben Jonson, as well as all four folios of Shakespeare. To him, student theater encapsulated much of what was so special about academic experience: an opportunity to collaborate with his classmates in an activity deeply bound up with institutional tradition.

In a revised 1625 edition of the Essays, Francis Bacon included a new essay, “Of Masques and Triumphs,” which briefly discusses contemporary forms of theatrical entertainment. Such performances, it begins, “are but toys to come amongst such serious observations”: unworthy of being discussed alongside topics like “studies.” Widener could not have disagreed more. For him, A Scrap of Paper and The Lotos-Eaters were not separable from his more “serious” academic endeavors, but rather an integral part of them, the very essence of the student experience at the schools he so adored. As far as Bacon’s Essays went, he no doubt preferred the 1598 edition.