Two years after commemorating its seventy-fifth anniversary, Houghton Library will have something else to celebrate before its eightieth: the largest renovation project in its history.

Though a plan to revamp the library—Harvard’s principal repository for rare books and manuscripts (see “An ‘Enchanted Place,’” March-April 2017, page 36, on the anniversary exhibition)—has long been simmering, the project’s timing was spurred by a donation of both books and money from Peter J. Solomon ’60, M.B.A. ’63, chairman and founder of the eponymous investment-banking firm. The proposed construction centers around the idea of accessibility, both literally and figuratively. Solomon and Thomas Hyry, Fearrington librarian of Houghton Library, hope the changes will draw more people into a space that often feels underused.

Solomon said that as students, he and his classmates frequently walked past Houghton to get meals in the former Freshman Union. “We all used Lamont and Widener, but nobody ever went to Houghton.”

When deciding where to donate his collection of children’s literature, manuscripts, and illustrations, he considered Princeton’s Cotsen Children’s Library, the Morgan Library & Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—but as a former Harvard Overseer, he always suspected the collection would end up in Houghton. In 2017 he committed to donating it, but with a caveat: that Harvard make some changes to open Houghton up to more people. Solomon said Houghton sits on “prime real estate,” but often doesn’t seem like it.

He was a big fan of the plans the library drew up in response, and when Harvard asked for help in completing the project, he and his wife decided to donate a majority of the funds required for its completion. “And the reason I’m not only giving them my collection but giving them a good deal of money is I didn’t want this to be posthumous,” he said, laughing. “I have no plans to leave this earth, but I don’t do the planning. You know what they say, ‘Plans are worthless; planning is essential.’ ”

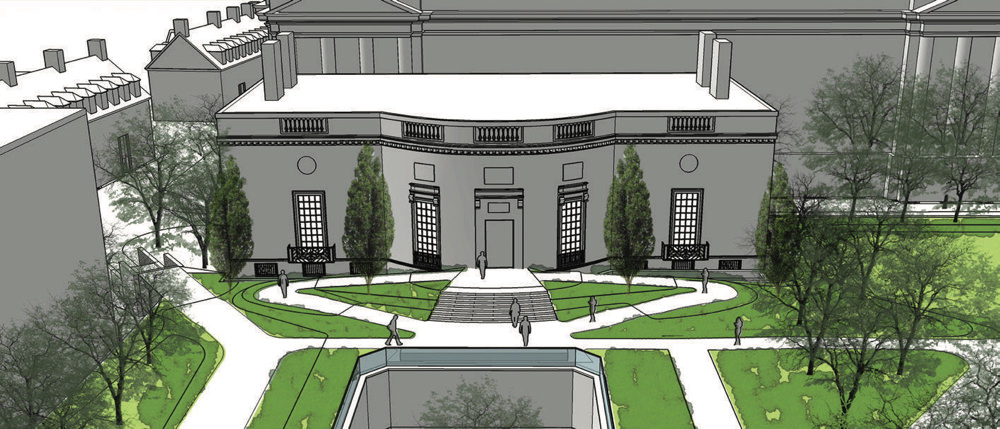

Houghton’s brick façade will not change, but the landscape directly in front will undergo a facelift. When researching the building, Ann Beha Architects noticed that the original drawings of Houghton’s entry differed from what was actually built. This, Ann Beha said, gave them the feeling that they could re-develop the area. Where there’s now a small staircase and podium—typical of Georgian architecture—her firm has designed a fully accessible entrance with softly graded symmetrical walkways that meet at the entry door. The plans also include a small gathering place in front of the library and a central staircase.

“My bet is that everyone will feel that they can use the inclined walkways,” Beha said in an interview, “because it’s going to be a natural way of coming up to the building.”

An aerial view shows the redesigned walkways and new landscaping in front of the library, giving Houghton more presence within the Yard.

Rendering courtesy of Ann Beha Architects

Today, wheelchair users must enter Houghton through Lamont or Widener, accompanied by a Harvard staff member, via an underground tunnel and a staff elevator. This issue was a key driver of the project. “We want to comply with both ethical and legal components of accessibility,” Hyry said. “But more than that, we want to be a library that’s open to all. And if you can’t navigate a set of stairs, that’s a very difficult thing.”

Houghton’s interior spiral staircase will remain the same, but the building gains a new elevator, its first for non-staff use. Anne-Marie Eze, director of scholarly and public programs, said librarians expected that finding space for a new elevator would be tough. It turned out, happily, that an elevator shaft was part of the original pre-World War II design, making installation surprisingly easy.

The library’s lobby, which has remained roughly the same since its inception, will also undergo some changes with the goal of “enlivening” the space. Its eight encircling bookcases will be replaced by exhibitions displaying some of Houghton’s holdings, with the objects changing throughout the year. And removing two of the existing bookcases, Hyry said, will let daylight shine through the lobby’s two large windows. Currently, most of the light illuminates a locker room on one side, and an office on the other. “Research libraries have a sense of being very dark, and that’s dramatic, but at times, with our weather in New England, you want to bring a little light in,” Beha said. “Conservation standards have kept us very focused on managing light, but I think we’re going to be able, as we study the options, to introduce a little more daylight into the spaces.”

Future visitors will also notice a new security system. Now, a guard sits at a desk in the lobby, responsible for welcoming and orienting guests and ensuring that the collections stay safe—a combination of duties Hyry acknowledges is not ideal. In the new plan, visitors will be greeted by a designated staff member—a new position—and will interact with security only on their way out, through a separate exit door.

“We want you to come into this library and think, ‘I’m somewhere special. This place is beautiful, it’s ornate. Something really important goes on here,’” Hyry said. “We don’t want you to think, ‘Oh, do I belong here?’ We want it to convey a sense of belonging.”

Outside the lobby, perhaps the biggest change will come to the reading room—the only place researchers can spend time with items from the collection. Staff sit toward the front of the room, monitoring it and assisting researchers. But as it stands, it’s a little too one-size-fits-all.

“A very specific point needs to be made,” Hyry says during a tour, whispering so as not to disturb the dozen or so people doing research. “This room is too loud….We want spaces to enable interaction, and we want some places to be quiet. Because if you’re coming from France for a week to study things you can only get here, then you want an optimal study environment.”

The new plan breaks the room into three sections, allowing groups to work together without disturbing those who would prefer to do their research in silence. Staff will continue to monitor and work with guests, but there will be a separate sound-proof entry and help-desk area.

A floor below all this, Houghton’s bathrooms will be expanded and made code-compliant. Its stacks, located in the basement and sub-basement, will have to be re-arranged during the construction (those under the bathrooms in particular), with all books carefully tracked and moved.

Fortunately, nearly all the collection will be available for use in a temporary home in Widener’s periodicals room. It’s not an unfamiliar place for these holdings: before Houghton was built, Harvard stored them in this same venue, once called the “Treasure Room.”

“There’s something that we take some satisfaction from in this plan,” Hyry said. “It’s something of a homecoming.”

When Keyes Dewitt Metcalf arrived as director of the Harvard University Library and librarian of the Harvard College Library in September 1937, he quickly realized three things about the University’s collections: they were vast, varied, and not particularly well-preserved. Widener (completed in 1915) lacked air conditioning. This created a sticky situation—sometimes literally—for the rare books housed within. Librarians struggled to keep their collections protected from the dry heat of the winter, humidity of the summer, and increasingly pervasive pollution from the city.

Within months of his appointment, Metcalf put three proposals in front of the Harvard Corporation. The first was for a separate rare-book library, connected to Widener by tunnel. The second was for an adjacent library for undergraduates. The third was for a storage facility to be shared with other libraries. The three plans were quickly approved, and aided by a donation from Arthur A. Houghton Jr. ’29—himself a book collector. Houghton and Lamont arrived in short order; the depository didn’t come along until 1986.

The torrid pace of plan approval and funding was matched by the pace of designing and engineering. Houghton chose William G. Perry, most famous for his meticulous restoration of Colonial Williamsburg, as the chief architect. Construction got under way almost immediately, which proved a major blessing: the library was completed shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“Houghton Library was built at about the last moment in which it was possible to do such work,” wrote Bainbridge Bunting, Ph.D. ’52, in Harvard: An Architectural History. “A few months later shortages of materials occasioned by the war would have made construction impossible; after the war the cost of materials and labor would have precluded such an undertaking for financial reasons alone.” Lamont Library, completed just after the war, shows how big an architectural difference a half-decade could make.

To complete the first project so quickly required a major commitment from the former Treasure Room’s small staff. In A Houghton Library Chronicle: 1942-1992, former Houghton librarian William H. Bond called the movement of books from Widener to their new location “a do-it-yourself operation,” in which staff was often charged with moving books at night and on weekends:

This “home industry” aspect of the move into the new library and the preparations for its dedication, necessitated by budgetary limitations on the size of the staff, placed considerable burdens on those involved. At the same time it created a sense of involvement and the espirit de corps that have pervaded the Houghton Library during most of its history.

Houghton’s espirit de corps remains. When asked how, logistically, the books will be moved, Hyry looked helplessly to the sky. “I’m smiling because I think it’s very likely that almost every member of the staff is going to have to move something at some point,” he said with a laugh. “And when I speak about it publicly, for good reason, I talk about how exciting it is, because it’s kind of literally a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to do something great in this building….But it’s not a small project and it’s incredibly disruptive to our staff, and they’re being heroic about it.”

“It’s definitely all hands on deck,” Eze added.

In an ideal world, the library wouldn’t have to close at all, but the scope of the renovation all but necessitates shutting the building for a year, beginning in September 2019. For Hyry and Solomon, though, the wait will be worth it. Houghton is already planning for many more visitors after the renovation is complete, and Solomon said he’s received emails from alumni expressing enthusiasm about the project and the future of the library.

“I think it’s just heightening the interest in and teaching and use of books,” Solomon said. “And it will please my wife because now my collection is going someplace, and she can get rid of the clutter.”