Kennedy School dean Douglas Elmendorf seemed to anticipate what was coming Thursday evening as he introduced an Institute of Politics event featuring President Lawrence S. Bacow. Standing onstage at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum, Elmendorf exhorted those in attendance, to be “respectful audience members,” to “listen, think, and learn” and to save their comments until after the talk.

Two minutes later, just as the discussion was about to begin, 30 or so student protesters stood up from the audience, holding signs demanding that Harvard divest its $39-billion endowment of companies involved in the fossil-fuel and prison industries. Several climbed onstage, where Bacow and Bridget Terry Long, dean of the Graduate School of Education and Saris professor of education and economics, had planned to talk about universities’ role in addressing economic inequality and opportunity. When Elmendorf asked the protesters to move to the back of the room and “make [their] point” from there, the students began to chant: “Disclose, divest, or this movement will not rest!”

Thursday’s demonstration was the latest and most forceful by two student campaigns that have intensified their efforts in recent months, Divest Harvard and Harvard Prison Divestment. Two days earlier, protesters had unfurled a large banner reading “Harvard Profits from Womxn’s Imprisonment” behind Bacow as he spoke at the University’s gender equity summit in the Smith Campus Center.

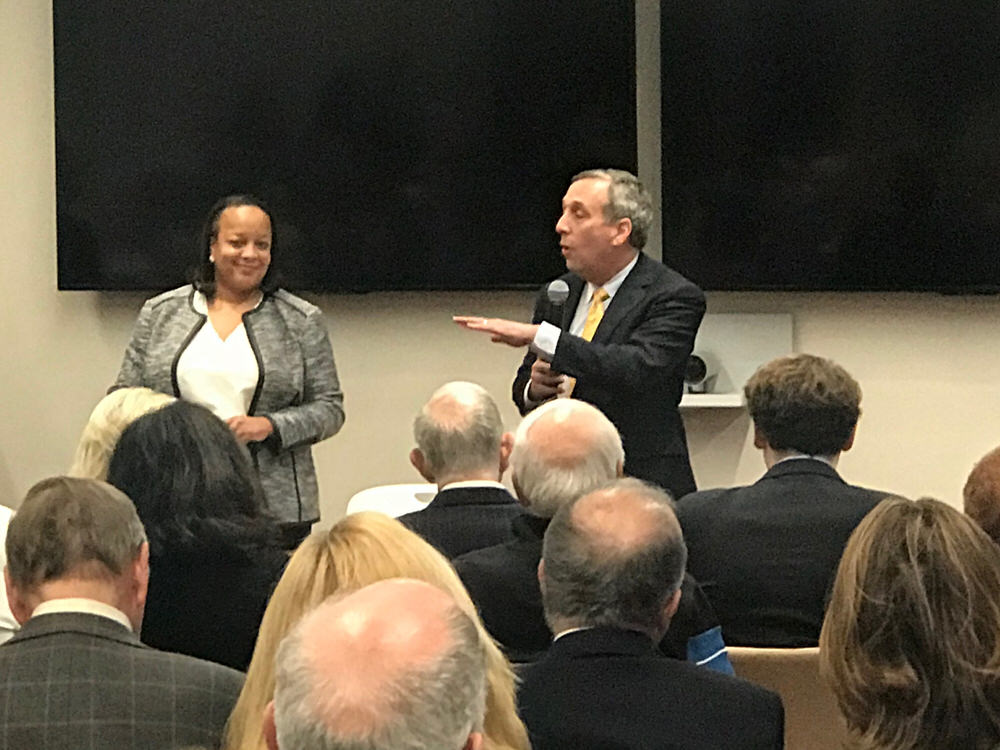

At the Kennedy School, the president rose to address the chanting students. Echoing comments he has made earlier, including in a meeting with students from the prison divestment campaign, Bacow said that he would respond to “reason,” but not “pressure.” He said he would be “happy” to meet with them again, and repeated Elmendorf’s request that they move to the back of the room. “You’re not being helpful to your cause,” he said. The protesters did not move, and began chanting anew. After a few minutes, Bacow, Long, and Elmendorf left the room, followed by most of the audience, and reconvened in a fourth-floor classroom.

“Thank you all for your flexibility,” Bacow said, as listeners shuffled in and settled into the chairs that staffers were hastily assembling. “Universities are places where people express opinions, and they often express opinions sharply. We have to expect that.” Without protest, universities would be “dull places indeed,” he joked. “But that said, I do wish they’d taken the long view, because I mean what I said,” about reason and pressure.

With that, the thirtieth annual Wiener Lecture, endowed by audience member Malcolm H. Wiener ’57, J.D. ’63, founder of Harvard’s Wiener Center for Social Policy, carried on.

Responding to Long’s questions about Harvard’s place in the world, its responsibility to address “difficult problems and painful divisions,” Bacow said that the University should “model the behavior that we would like to see in the rest of the world.” He added, “I think we need to be quick to understand and slow to judge…. If we believe in the truth, we have to be willing to have people challenge our thinking, test our ideas. Truth needs to be revealed, it needs to be tested. And it can only be done so in the anvil of ideas.”

Photograph by Harvard Magazine/LG

When Long turned the conversation toward research on the decline in social mobility and how universities can grapple with the structural inequalities that their scholars are uncovering, Bacow replied, “We can do a number of things, but we can’t do everything. Some of the issues we’re dealing with… are really structural changes in our economy, which go well beyond the capacity of any one institution, or even a set of institutions, to address. We can influence things at the margin. We can influence things by who we educate, and how we educate them.”

Later, he said that inequality is “corroding society writ large—not just this one, but others” and described its “fractal quality”: “We can look at inequality as it exists between nations, in the developing world. We can look at inequality within nations, within regions, in our backyard. On our own campuses.” He noted that growing inequality, left unaddressed, “will erode the social capital that actually allows our institutions to operate.” He recalled his childhood in Pontiac, Michigan (“Pontiac is to Detroit as Lowell is to Boston,” he explained), where the past few decades have upended the guarantees of a stable, comfortable middle-class existence that previous generations relied on. “And I worry that with growing inequality, with the lack of opportunity for so many at the bottom of the income strata, we are destroying hope, and when hope is gone, I think fundamentally society changes in a big way.” Universities can help, he said, “not just by shining a light on some of the structural issues we have to address, but by developing new technologies, new industries, being the engine of economic growth that institutions like this have traditionally been.”

There were other questions as the event wound toward a close—audience members asked about mitigating economic inequality among students on campus; and about the reshaping of society by artificial intelligence. Bacow talked about the grants that give needy students “walking-around money” to join classmates for evenings out and recreational activities they might otherwise have to skip, about the ethics discussions now embedded in the computer-science curriculum, and about the importance of returning to a liberal-arts education that teaches critical reasoning. Then a man in the audience—a Harvard graduate and an immigrant, he said—asked about not only hopelessness in the face of inequality, but anger. “It seems universities should feel somewhat responsible for creating good citizens,” he said.

Bacow’s answer brought to mind how the evening had begun. He reiterated his point about Harvard being “a place where we would model the behavior we want to see in the rest of the world,” and added: “Because let’s face it, if we can’t figure out how to do it here, on this campus where everybody is smart, where everybody is committed…. If we can’t make this work here, there’s very little hope for the rest of the world. So we need to work hard, embrace these values, and create the kind of community we hope to see elsewhere.”