There are three sides to every story—yours, mine, and the truth—and no one is lying.

—Anonymous

On July 17, 2017, my world turned upside down when I discovered that the man who raised me was not my biological father. What followed was a challenging path of learning and insight into family truths that ultimately brought great joy and made me a better person.

I am a biomedical truth seeker—looking to gain insights into human biology and our genomes in order to mitigate suffering and death from disease. By analyzing DNA variation in persons with and without disease, my research is providing blueprints for therapeutics that are safe and effective.

Good fortune has offered opportunities to realize my dreams. I’ve run a large lab with many of the best young trainees and scientists in the world during the past four decades at Harvard, and I co-founded the Broad Institute—now a 4,000-person biomedical center seeking “to propel the understanding and treatment of disease.” Following human biology-informed blueprints, my trainees and I are catalyzing the development of new types of medicine in diseases ranging from cancer to malaria. In the past 30 years, I’ve started a half-dozen biotechnology companies that have delivered novel medicines—including ones at Vertex Pharmaceuticals that are closing in on defeating cystic fibrosis. I’ve also been happily married to my true love, Mimi Packman, for 38 years.

These circumstances are highly unlikely. The physical and emotional trauma I experienced as a child and teenager, inflicted by my father, taught me the art of compartmentalization. This skill provided an eraser that enabled immediate removal of unwanted events. Only now do I realize that my mother, my angel and protector, 11 years younger than my father, also excelled at this, and I suspect I learned a great deal from her, albeit subliminally. In the worst of times, such as the beating from my father that left me (literally) broken and hospitalized, my sweet Cajun mother was there for me, flying up the stairs to protect me even when she, too, then suffered the consequences.

I was unaware of many factors about her life and mine—she artfully managed to deflect every effort to inquire, most effectively by responding, “Have I told you how much I love you?”—and it is difficult to know whether such knowledge would have been useful if she could have shared it with me. All I know is that my mother loved me unconditionally, showed that love continuously, did everything she could to give me the life I have enjoyed in adulthood, and is the reason I am where I am today.

Family secrets began to unravel on that summer day in 2017. My older brother, Tommy, with whom I have a close relationship, asked for help analyzing his 23andMe results: we were both seeking insight into our risk alleles for Alzheimer’s, which had taken our mother’s life.

After refreshing our browsers, I knew instantly that my biological father was not the man who raised me. Tommy and I share the 25 percent DNA identity of half siblings, not the expected 50 percent, and our father-contributed Y chromosomes differ. After I struggled to get the words out, my brother responded, immediately and dispassionately, “Well of course, that makes perfect sense.” That only compounded my surprise and bewilderment. But it also instinctively resonated with me. I knew he was right, even though we hadn’t established which of us had the surprise father. I had lived with the sensation of being a family alien for 62 years, yet only at that moment did I realize it was true.

The man who raised me, my father Thomas Schreiber (known to my childhood friends as “The Colonel”) was a brilliant, ethical, yet challenging and complex man. He was also tall and physically imposing, and his army training, rank, piercing blue eyes, and intellect gave him a special aura. I imagined he was an equal-opportunity physical offender toward his family, including Tommy and my dear sister, Renée, only to learn later that his wrath was focused on me. How could I have been unaware of this? When you are told by your father that whatever you experience is entirely the consequence of your actions alone, you are not predisposed to share. Not with your family or even your very best friends, including my best friends who had shared with me their unimaginable cruelties, including family betrayals, rejections, deaths, and familicide. You use your magic eraser. You create your own truths.

An Alien to Oneself

The sequelae that followed that summer-day discovery comprised three phases: the surreal phase; the unmoored phase; the joyful in-the-hunt-and-discovery phase.

“Who am I? From where do I come? And who is this unknown man living in my body, coursing through my veins?… Would I ever find the truth?”

In the first phase, I was numb: no shock, anger, disappointment—just bewilderment. It was so hard to grasp. Unimaginable. It was hard to think clearly. And yet, a tiny bit of relief. Maybe truth would yield clarity and understanding of my father’s actions. This secondary sensation was the beginning of a wholly unexpected change in my internal being.

The second phase—feeling unmoored—was by far the hardest. Who am I? From where do I come? And who is this unknown man living in my body, coursing through my veins? I would subconsciously shake my hands trying to get him out of me. And worst, with my mother and the father who raised me both deceased, would I ever find the truth, get to the answers I was seeking? When you think you understand your origins, there is no obsessive need to explore and connect; you are satisfied knowing there is an origin and your ancestors and family members can be searched and contacted whenever needed. But when that assumption is taken away, you truly are an alien.

And I wondered: was my mother supported and loved at my conception? This was my central focus—even more than determining the identity of my father. But the latter was the best way to answer the former.

My two older siblings and subsequent DNA analyses proved that my parents were able to conceive a child. This, and other observations of my mother and father as I grew up, made it certain to me that my conception was conjugal rather than “donor-derived,” a term associated with in vitro fertilization methods. Those searching for their sperm-donor fathers go through much of the same emotional turmoil I did, yet there are differences. My biological father was not an anonymous sperm donor, but who was he?

And so I transitioned to my scientist mode, where I have developed some problem-solving skills related to my work. And as I tried to solve the mystery, I realized there were two men living in me: two mysteries to solve, and two new families to discover.

Discovering My First New Family

I’ve become adept at integrating DNA analyses with genealogical tools. My approach is related to the one originally used to deanonymize persons from otherwise anonymous databases, and more recently to identify the Golden State Killer; indeed, a current personal focus is on identifying missing persons with the humanitarian organization DNA Doe Project.

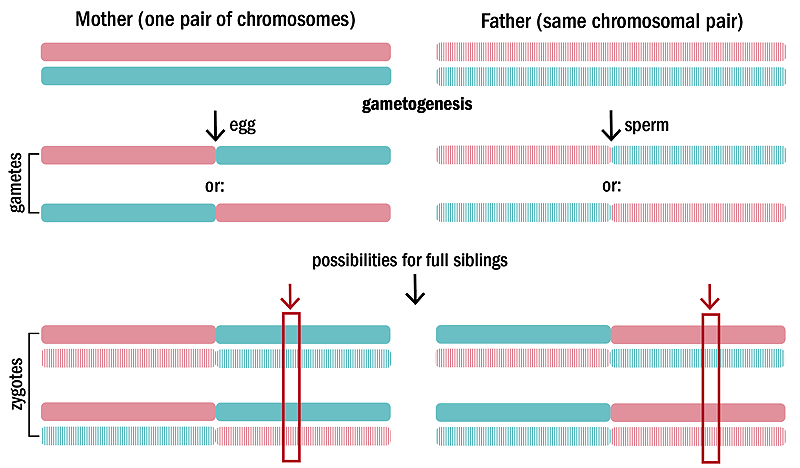

A key feature of this analysis considers both the “recombination” of chromosomes during the making of germ cells (sperm and eggs) and fertilization, which yields a zygote having both maternal and paternal genomes. Each of your chromosomes resulted from an act of conjoining your grandparents, even if they were no longer alive when your parents made the germs cells that gave rise to you. Each individual egg and sperm is unique, having its own genome resulting from the endless number of combinations of conjoining acts. Each of our moms made tens of thousands of eggs and our dads made millions of sperm. Each child results from one unique and specific egg and sperm—so our existences are truly remarkable. We each won the improbable zygote lottery!

This simplified illustration shows how just one pair (of 23) of maternal (pink) and paternal (blue) chromosomes from a mother (solid) and father (stripes)—inherited from their own parents—can be passed down in a single generation. Below the parental chromosomes are the four possible germ cells (gametes) resulting from a single genetic recombination, and the four possible zygotes that can be generated during fertilization from those gametes. (In reality, gametes result from multiple recombination events). The zygotes represent the four possible genetic outcomes for children of the mother and father.

DNA genotyping entails looking at hundreds of thousands of sites in the genome, which provides statistical robustness; the red boxes denote the genotype of just one such site. Now, imagine comparing the genotype of one full sibling—for example, a child resulting from the upper left zygotic pair of chromosomes—at this specific site, to a second full sibling, who would have equal probability of having any one of the same four possible zygotic chromosome pairs. If we look just at the two rectangles, the probability of two full siblings being identical at that locus on both chromosomes is one in four, or 25 percent. The probability of two full siblings being identical at that locus on a single chromosome is four ineight, or 50 percent. The probabilities for half siblings, who share only one parent, on the other hand, are 0 percent and 25 percent, respectively.

Chart courtesy of Stuart Schreiber

Chromosomes in germ cells are mosaic combinations of the parental chromosomes. This remarkable fact of inheritance provides a foundation for relating the amount of DNA identity between any two persons and the number of generations likely separating their last common ancestors—parents for siblings; grandparents for cousins; great-grandparents for second cousins; etc. This, together with the miracle of the Internet, where, for example, obituaries provide a wealth of genealogical information, permits the stitching together of plausible ancestral trees. With additional DNA relatives, the resolution increases until eventually the final tree is a certainty.

Within two months of searching public and private DNA ancestry databases, identifying DNA relatives and the amount of DNA identity, and computing, constructing, and connecting family trees up and down multiple generations, I eventually discovered the identity of my biological father, whom I had code-named “the crybaby” since my latent but previously suppressed ability to cry had been fully unleashed during this period. Crying was not part of my childhood: it was in my child’s mind a sign of weakness and therefore something I would never show my father throughout adolescence. Instead, after receiving a blow, I would respond, “Is that all you’ve got?”

DNA seemingly left no uncertainty about the solution to my puzzle. But where was this man at the time of my conception in early 1955? Was an encounter with my mother even geographically possible?

Newspapers.com revealed this mystery person had lived within walking distance of my mother’s home. (This led to a loud and joyful shriek at five o’clock one morning that startled my poor wife out of her deep sleep!) In 1955, Joseph (“Joe”) was a handsome and charming young bachelor, recently returned from military service at the end of the Korean War. He was by all accounts a kind, generous, and caring man (and he cried easily!)—exactly as I had imagined. In my mind, Joe provided my abused mother with kindness and humanity when she was in great need—and I am the consequence. In comparing a series of paired, age-matched photographs of Joe and me, I realized just how much of a physical clone I am—we share the same eyebrows, eyes, noses, ears, chins, and even Adam’s apples. And we were both bald by age 35!

Identifying my biological father was a key first step in overcoming my sense of being untethered. He had died, but I discovered five new amazing half-siblings and many new cousins. Not knowing my origins had led me to a profound need for connectedness, and given me a voracious appetite for gaining family connections. In the past 18 months I have thus far identified 150 DNA-validated living family members and built a family tree of more than 2,500 ancestors. They go as far back as my maternal great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother, Emashapa Panyouasas, the daughter of the chief of the Choctaw Nation in the Mississippi Gulf Coast in the early eighteenth century.

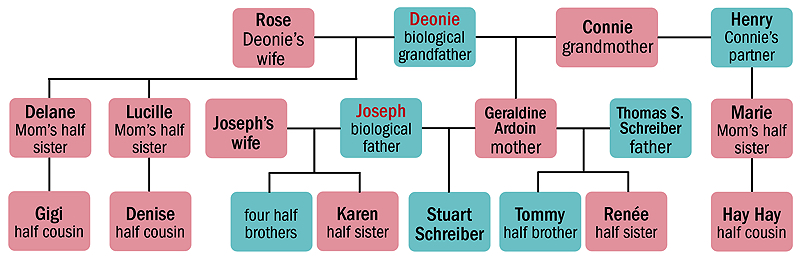

Emashapa explains a large chunk of Native American DNA on my chromosome 17. But along that path, something puzzling arose that gained clarity only over time. Emashapa, for example, could not possibly have had Hungarian (paternal grandfather) or Irish (paternal grandmother) origins, and any link to Cajuns would seem tenuous at best. Indeed, a sizable subset of my DNA relatives simply made no sense—until I considered that the man described as my mother’s father (my maternal grandfather, Henry, conveniently alleged by my maternal grandmother, Connie, to have died immediately prior to my mother’s birth) was in fact not her biological father.

…and My Second New Family

Opening my mind to the possibility of another false paternity, and applying the skills I had honed from my earlier search, revealed a DNA-guided path to my mother’s actual father, Deonie, and a second new family. Because Deonie was a member of one of the original Mississippi settler families, and there have been decades of inter-family marriages among those settlers, my sleuthing this time was far simpler, even though, like Joe, Deonie had never submitted his saliva for DNA analysis. Formidable DNA and genealogical tools enabled me to bridge this gap.

My first-hand interviews of these new family members, and discoveries of family artifacts, have illuminated my mother’s origins and provided powerful insights about her early life. She was born of prostitution (her mother, Connie) and moonshining (her father, Deonie). That she endured life first in a brothel and then in the Catholic convent to which she was delivered sheds much light on her reticence about describing her childhood in any detail beyond conveying great displeasure with the nuns who raised her and great pleasure in taking refuge in the local library, where a librarian showed kindness and patience, offering my mother a life raft from abuse, much as Joe would provide one later.

Family tree showing family members mentioned in the text.

Chart courtesy of Stuart Schreiber

I’ve learned how my grandfather, the moonshiner, purportedly on the run after killing a man in Mississippi, and my grandmother, the prostitute, came together, in a series of highly improbable circumstances. But without this unlikely event, my mother wouldn’t have existed, nor would Renée, Tommy, and I. (I like to think that I won an even more improbable zygote lottery twice!) These circumstances have triggered a fascination with the early- to mid-twentieth-century Mississippi and Louisiana cultures, which were surprisingly separate and distinct in this period preceding facile travel. It has opened my mind to those cultures and their current variants, and offered helpful life lessons as described later.

My mother created a truth of her childhood by erasing the abuse and mayhem and focusing on the library, and later Joe. She created her truth of our family, keeping paternity to a simpler version. She may have passed through her own surreal and unmoored phases, but compartmentalizing was her megingjörð—her magical belt that gave her the power to reach her joyful phase and achieve her dream of providing love to her children.

I’ve often wondered how my truths would be received by her, but of course this is unknowable, as they were only revealed three years after her passing.

Who Knew What?

It will likely be impossible to learn the answers to the big questions remaining in my mind, but inferences lead me to some best guesses. More importantly, these questions are not like those that led to my unmoored phase. I have a deep desire to know these truths, but am comfortable realizing that may not be achievable.

“My mother’s best friend has said she wondered, from her first meeting with my mother, why my father hated his younger son, but not his other two children, for no apparent reason.”

Did my father know I was not his biological son? I am nearly certain he did, although some family members are less so. Several months after my birth in New Jersey, my father left for Kansas for nearly a year, leaving my then-fragile mother alone with her new baby and two other young children, one in struggling health. My mother once confided, “This was the worst year of my life.” My father returned from Kansas to take the family to France, where he was newly stationed. I believe my parents tried to put their past behind them for the good of the family, putting the secret in their figurative lockbox. But his physical actions toward me, often conducted behind a closed door in his den, offer additional clues. My brother has shared his observation that “that only happened to you.” My mother’s best friend has said she wondered, from her first meeting with my mother, why my father hated his younger son, but not his other two children, for no apparent reason. My father was less adept at compartmentalizing. He tried to believe one truth but couldn’t help returning to the one hidden in his lockbox.

Did my mother know? Almost certainly. Every element of my history with my loving protector mom now fits perfectly into the new fact-based narrative.

Did Joe know? Possibly not. Based on all I’ve since learned from my new relatives, his strong family relationships would have demanded sharing—making a secret hard to maintain, and “Grandma K,” the matriarch of the family, would not have tolerated separation from her grandson, born under any circumstances.

What did my mother know about her father? It is unlikely she knew Deonie’s identity, given her mother’s circumstances, but I am nearly certain she was aware of the likelihood that her father was someone other than the man her mother said had died just before her birth. Her use of her magic eraser may have led to her first encounter with a lockbox.

Did Deonie know? Yes, as did his wife, Rose, and his daughters, Delane and Lucille, although the daughters knew only of my mother’s existence. They were unaware that they were all living in close proximity in neighboring towns in Louisiana, where Deonie had for some time been appointed sheriff—and his superior was well known for providing protection and cover for gambling and prostitution. Indeed, my grandmother learned her trade as a prostitute when she was “put to work” by her father at just 14 years of age. Most tellingly, Rose told Delane about my mother after Delane’s classmates teased her about having a secret bastard sister, and Lucille had two uncomfortable encounters with my grandmother Connie, including one as a little girl, when she was with her daddy, Deonie.

But one answer to “What is truth?” is “It depends on whose truth.”

Reconciliation

My relationship with my father evolved in a satisfying way, especially after it became evident that I might make something of my life. We discussed science and even published together (“Reactions That Proceed with a Combination of Enantiotopic Group and Diastereotopic Face Selectivity Can Deliver Products with Very High Enantiomeric Excess: Experimental Support of a Mathematical Model,”1987). He disapproved of the lack of rigor in the chemical sciences, in which I was trained, relative to his areas of physics and mathematics, yet paradoxically I received my first direct compliment from him in the early 1990s when I described my reasons for transitioning to the even less rigorous biological and medical sciences. Although his parenting skills were lacking, he excelled as a grandparent, showing affection to Renée’s and Tommy’s children that would warm anyone’s heart.

My mother and father, “The Colonel” (right), at the Pentagon, where he was awarded a Certificate of Achievement in October 1961

Photograph courtesy of Stuart Schreiber

My warmth toward him in his later years may best be described by my fear of his dying without either of us having shared the word “love.” I tried, on several occasions, but he deflected even an attempt at an embrace with a forceful handshake and strong extended arm. So on June 20, 1993, I left on his work table (which I had only recently received the privilege of using during my weekend visits) a letter that expressed the words he was unwilling to hear: “Dear Dad, On this Father’s Day, I want to share the things I have learned from you—honesty, integrity, and finding what we enjoy so we can do it well.…I love you. Your son.”

I waited for several months, hoping to hear from him, but to no avail. I queried my mother, only to learn that she knew nothing of the letter and had never heard my father refer to it. Then, maybe six months later on a return visit, while alone, I spotted an envelope on his otherwise pristine desk. A wave of guilt over my curiosity subsided when I read the face of the envelope—June 20, 1943, from my father and addressed to his father, Thomas Joseph Schreiber. The letter inside was easily accessed and its contents confirmed that it was indeed meant for me to see. “Dear Dad, Today being Father’s Day, it is appropriate that I write you how I feel about my dad. First, I am quite proud of you. Considering your early environment, your lack of opportunity, and the difficulties which confronted you in your youth, you have done a fine job in providing a good and comfortable home for your family…Thoughtfully, Tom.”

With this, we achieved a degree of closure about our complicated, but in the end respectful and caring, relationship. Years after his death, I found both letters together, tucked in a book in his private library. He never shared a word about them with either my mother or me.

Both of my fathers passed in the year 1996.

Becoming a Better Person

I have already noted one of the most unanticipated consequences of learning my origins and family truths: my tears flow easily now. I am no longer inclined to hide my emotions, and they are easily triggered—whether by seeing the love of a parent and child walking in a Boston park or by learning of another case of abusive behavior.

I view newly discovered family members as cherished persons with their own deep and remarkable stories, and have become eager to learn about their lives. Many of them (including dear cousin Hay Hay) have embraced me with great warmth and love. These discoveries have yielded endless joy. My wife and I have traveled the globe to meet new relatives and see my ancestors’ homelands—Budapest (paternal grandfather) most recently, with Northern Ireland’s County Tyrone (paternal grandmother) next in the queue. We have received gifts such as Grandma K’s flatware from Northern Ireland (with love from cousin Sharon), and learned many happy details of the father I never knew, including from my inspiring, survivor cousin Pat. I will never know him, but I listen regularly to an audiotape of his voice, lovingly given to me by my new sister Karen—with free-flowing tears every time.

My pilgrimages have included a family reunion in The Kiln, Mississippi, where Deonie was born (and the birthplace of my second cousin, NFL Hall of Famer Brett Favre—who would have imagined!), and a visit to Rotten Bayou, Mississippi, where Deonie’s family members were laid to rest. They also include a visit to Louisiana, my mother’s birthplace, where I met my mother’s previously unknown (to both of us) half-sister Lucille, whose Cajun smile, charm, voice, looks, and ability to radiate love are all those of my mother. Meeting Aunt “Cile” was like seeing my mother again, four years after her death. Lots of tears with that visit! I learned details of the life of my mother’s other half-sister, Aunt Delane, who is now deceased. But her daughter Gigi, and Lucille’s daughter Denise, cousins from my second new family, have become a close and integral part of our lives.

But the changes go beyond my emotions. I am a progressive who in the past would have asserted confidently my open-mindedness and nonjudgmental character. But I was wrong. Meeting my new families in The Kiln (Mississippi), Houma (Louisiana), Eatontown (New Jersey, where I was conceived), and Pécs (Hungary), among many other places, has exposed me in a new way to political and religious realities that, I now realize, were previously easy for me to dismiss. Now they feel different. They feel like my origins, reality, and family. It’s a lot easier to embrace a wider range of beliefs and values. This change is the most difficult for me to articulate—but it feels profoundly different. And I like it. I know I’ve become a better person.